Built 1828-30, Randolph Hall is the signature building of the College of Charleston campus. A National Historic Landmark, the building is one of three historic structures in Cistern Yard, and it appears in the university’s main logo.

Randolph Hall, the College of Charleston’s most iconic building, was originally referred to as College Hall and later as the Main Building.

The building’s stately appearance has made it a popular filming location for movies, television shows and news broadcasts. It serves as a stunning backdrop for the school’s signature Spring Commencement Ceremonies on Mother’s Day weekend and for performances during the city’s annual Spoleto Festival USA.

Named for Harrison Randolph in 1972, who served as the College’s president from 1897 to 1945, the building was the first classroom building constructed on campus. Today, in addition to housing several administrative offices, including the offices of the president and provost, Randolph Hall is the home of the College’s Classics department, making it one of the oldest academic buildings in the United States still in continuous use.

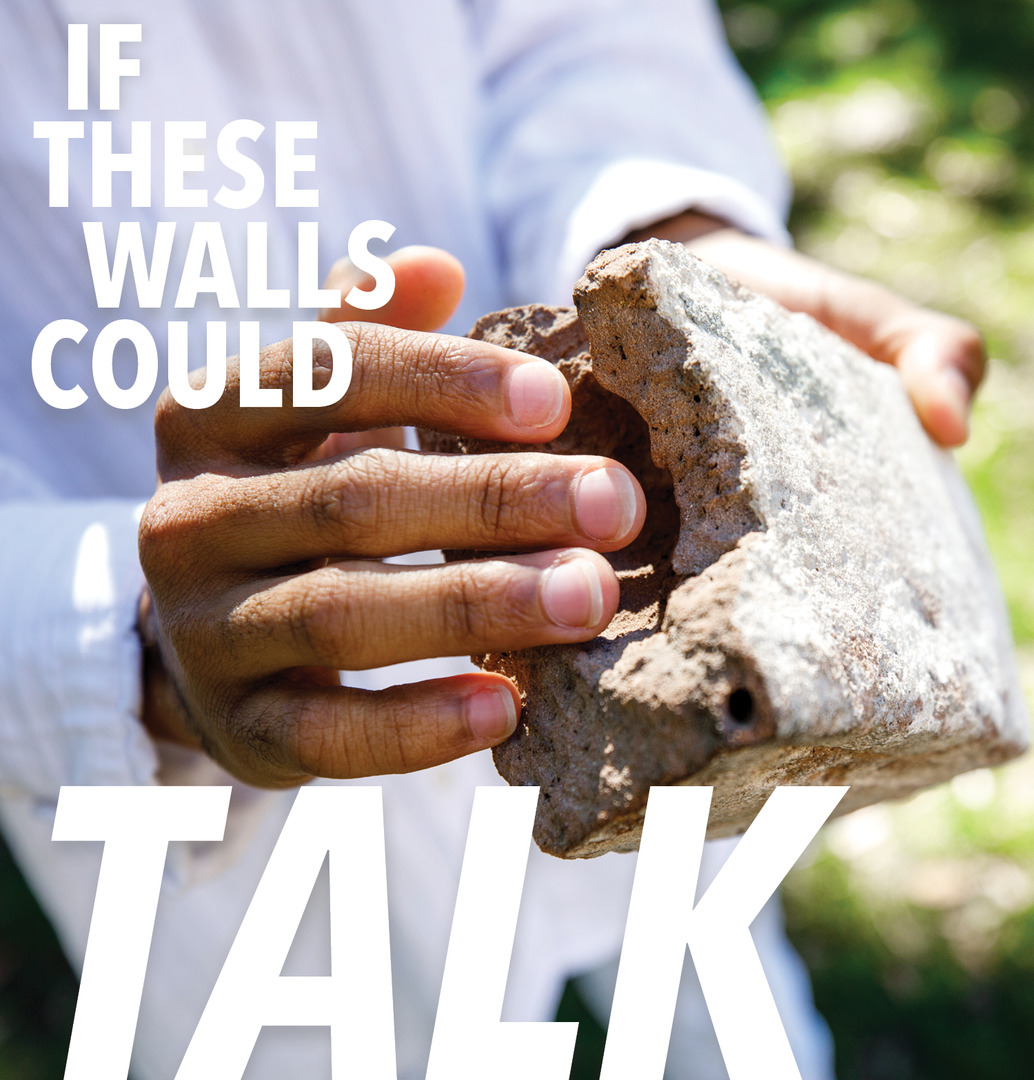

Construction of this building took place from 1828 to 1830. College records and other historical documents indicate that manual and skilled enslaved laborers worked under contractor and slave owner William Bell to construct Randolph Hall and to make later renovations and repairs. Four enslaved people have been identified in association with the original construction of Randolph Hall. Their names were Tom, Mudrey, Cuffy, and Peggy.

The original core of Randolph Hall has endured for nearly two centuries, surviving a major earthquake, multiple hurricanes and the Civil War, and serving as the hub of academic life for generations of students. However, the structure that exists today is actually a composite of several additions and renovations that occurred throughout the 19th century.

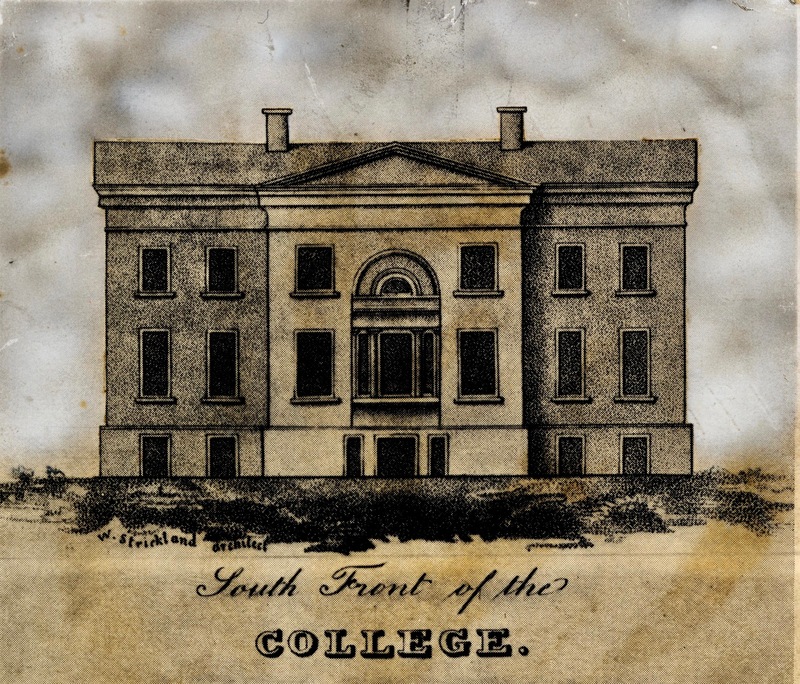

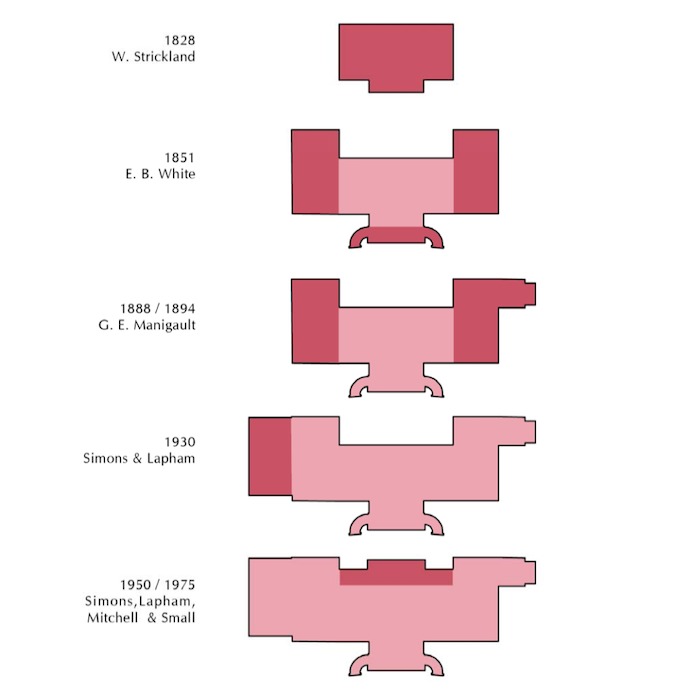

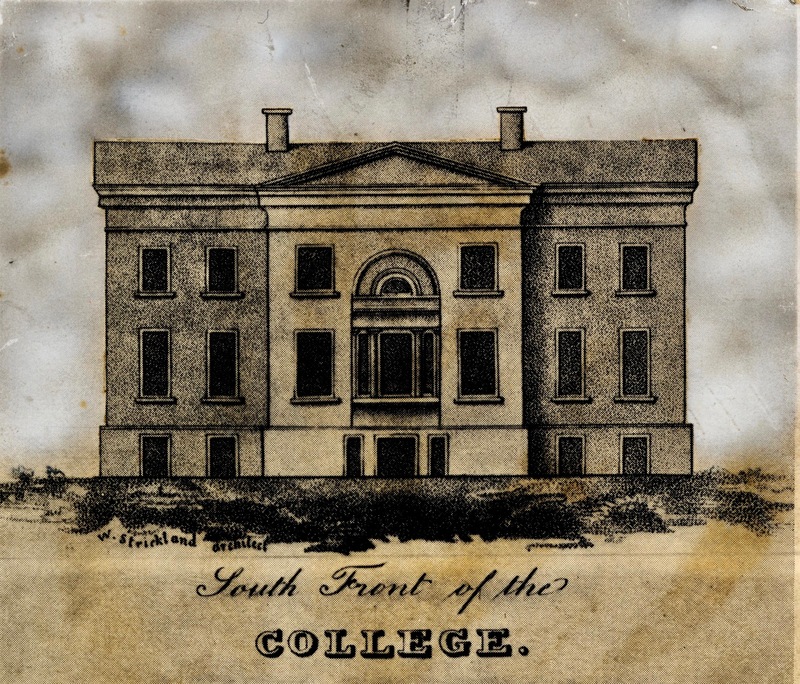

Prior to the construction of Randolph Hall, the College lacked a dedicated classroom building and instead relied on a deteriorating military barracks used during the Revolutionary War. Under lobbying from then-president Jasper Adams, the College’s trustees in 1826 began raising funds to build a new structure dedicated to the instruction of students, hiring Philadelphia architect William Strickland to design it. A cornerstone-laying ceremony marked the beginning of construction on Jan. 12, 1828.

The brick building – two stories over a raised basement – was originally oriented facing north along Green Street, and the south side of the building overlooking a large open yard. As part of the building’s construction, a high wall was erected around the yard and a decorative iron fence was built around its Green Street façade.

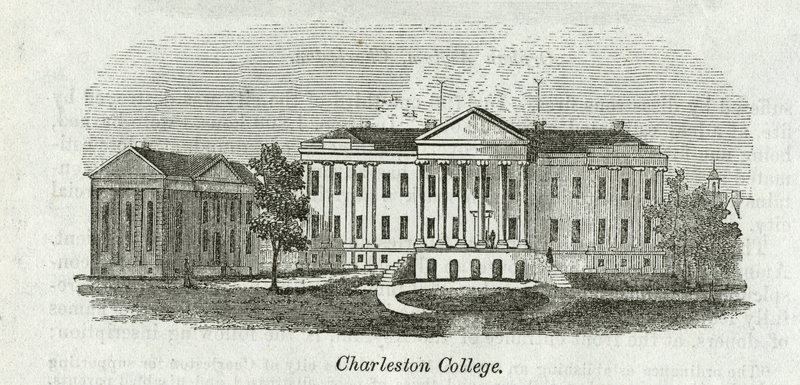

When Adams wrote to a friend in Massachusetts in December 1829, noting, “During the last two years, we have erected a large, beautiful & very convenient edifice,” the building looked much different than it does today. The wings that today extend to the east and west, as well as the signature portico and columns on the south side, were not added until 1850-51. These additions, designed by Charleston architect Edward Brickell White, reoriented the building so that the south side became the front, facing toward George Street. The original portico facing Green Street is believed to have been removed as part of the 1850s renovations, but portions of the wood beams that once anchored the old portico to the main building are still visible in the building’s attic. To accentuate the building’s new south-facing façade and the surrounding yard as the main entrance to campus, White designed an arched “Porter’s Lodge” along George Street. In addition, the high brick wall that had previously surrounded the yard was lowered and became a base for new iron fencing. What is believed to be a surviving section of the original high brick wall remains on the yard’s northeast corner along St. Philip Street. At some point between its completion and the subsequent 1850s renovation, the building’s brick exterior was covered in stucco.

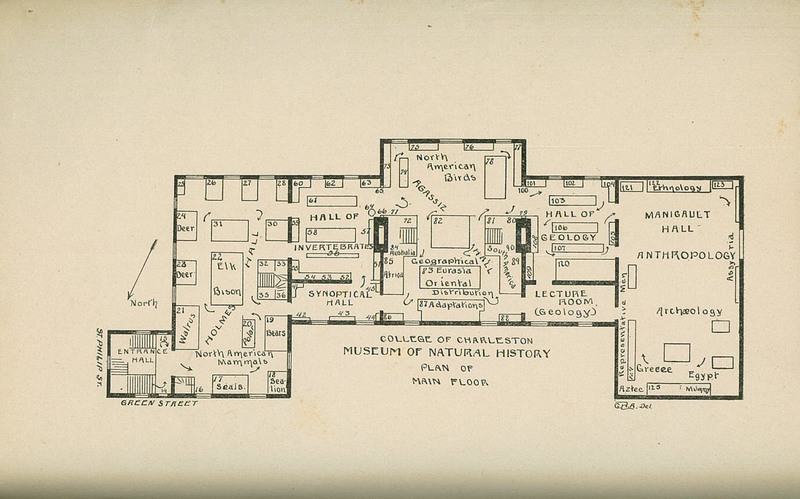

In 1852, the College opened a natural history museum on the third floor of Randolph Hall, and an observatory was installed on the roof in 1872-1874. In 1886, a major earthquake devastated Charleston and severely damaged the building. The east and west wings were torn down and rebuilt between 1888 and 1894 under the direction of Gabriel Manigault, a professor, amateur architect and curator of the College’s natural history museum. The portico was rebuilt in 1887. The east wing was rebuilt in 1888-1889 and the west wing in 1894. As part of the repairs to the east wing, a new four-story tower was added at the wing’s northeast corner to provide direct public access to the museum on the third floor.

Randolph Hall played a central role in the admission of the first women to the College. In 1917, Carrie Teller Pollitzer, a Charlestonian and advocate for education and women’s rights, petitioned the College to admit women. The proposal was initially rejected, but the College continued to suffer declining enrollment during World War I. In June 1918 Harrison Randolph, who had been staunchly opposed to co-education, relented, with the condition that a women’s lounge must be provided. Pollitzer led the effort to secure the necessary funds, and in September 1918, thirteen women enrolled at the College. Records indicate that women were assigned the lavatory on the third floor and “the center room on the third floor, facing south” was furnished “as a rest room for women students.”

The west end of the building was extended further toward College Street (later College Way) in 1930. In 1954, a clock was installed on the pediment of Randolph Hall – a gift from the Pi Kappa Phi fraternity that was founded at the College in 1904.

Following the College becoming a state institution in 1970, Randolph Hall was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1971 and again underwent renovations. Designed by architect and professor Albert Simons, the 1975 additions included a portico and elevator on the north side of the building. A fountain was also added outside the north entrance.

In 2007, the College began a multi-year renovation of Randolph Hall, Porter’s Lodge, Towell Library and Cistern Yard.

Audio

Images