Discovering African American History at the College of Charleston

A Reflection by Professor Emeritus Bernard Powers

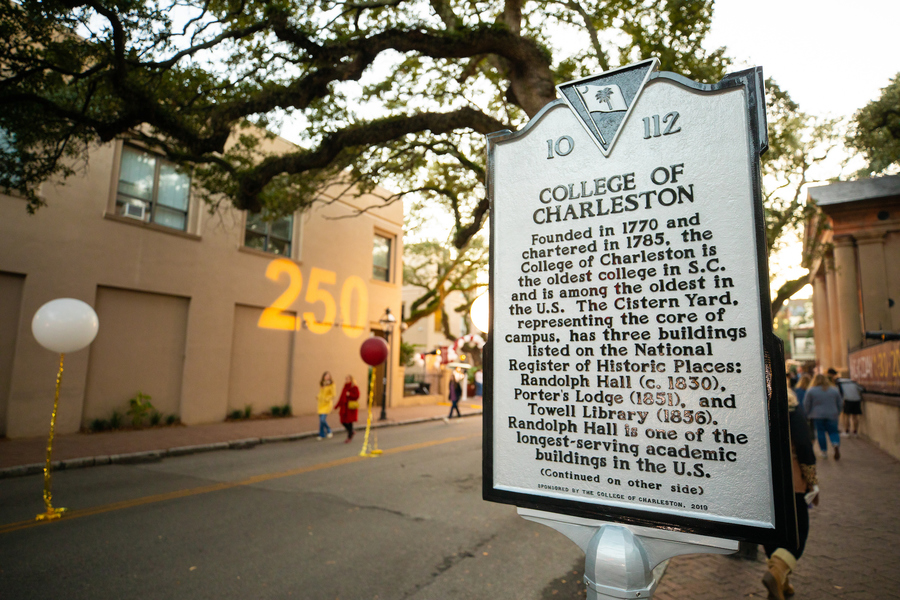

A state historical marker stands on George Street just outside of Cistern Yard. It was unveiled on Jan. 30, 2020, exactly 250 years after the Lieutenant Governor of colonial South Carolina proposed a college for Charleston.

With this marker and a number of research projects now underway, the College commits to telling a fuller story of its past. This state historical marker records the College’s accomplishments, but also its past exclusionary practices. These include the exclusion of women until 1918 and African Americans until 1967.

Below, historian Bernard Powers reflects on the African American experiences and contributions that are part of the College's history, some of which will be showcased on this website in the future. Powers is the director of College’s Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston, which is spearheading this upcoming tour of African American history at the College and in the surrounding neighborhoods. .

Although it has often been said that "a picture is worth a thousand words," this has not been true for the College of Charleston. When one enters Porter’s Lodge and strolls through our much-photographed campus, little is revealed beyond its visual appeal. Unfortunately, there has been little on our grounds to convey the deep and complex history embedded in the buildings, the landscape and the surrounding neighborhood.

The College’s history is at the very heart of early American history. Early leaders played critical roles in the American Revolution; three signed the Declaration of Independence and three others helped write the Constitution. Revolutionary-era barracks were among the earliest buildings the College used, and fifty years later, it became the nation’s earliest municipal college.

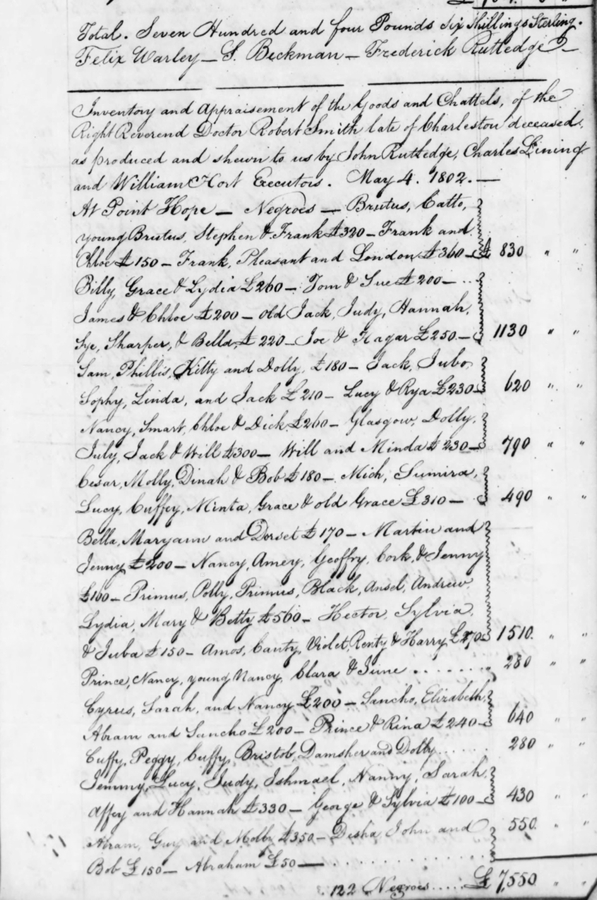

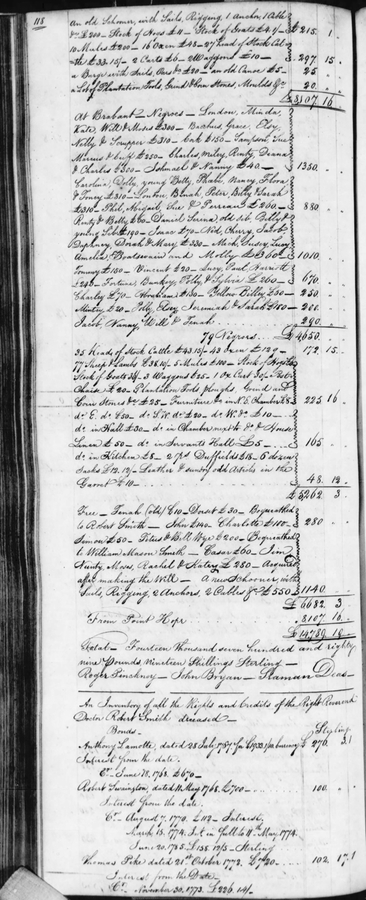

Stories about the College’s connection to slavery and subsequent issues of race are not as well known, because they have seldom been fully told. Many would be surprised to learn how organically intertwined these issues have been with the history of our institution. For example, Bishop Robert Smith, the first president, was a large slaveholder who used his own enslaved people to perform work on the campus; the College accumulated a considerable debt to him in part because of this. This indebtedness even influenced the way the campus was developed in the early years. We also know that slave labor was used to construct Randolph Hall in the late 1820s.

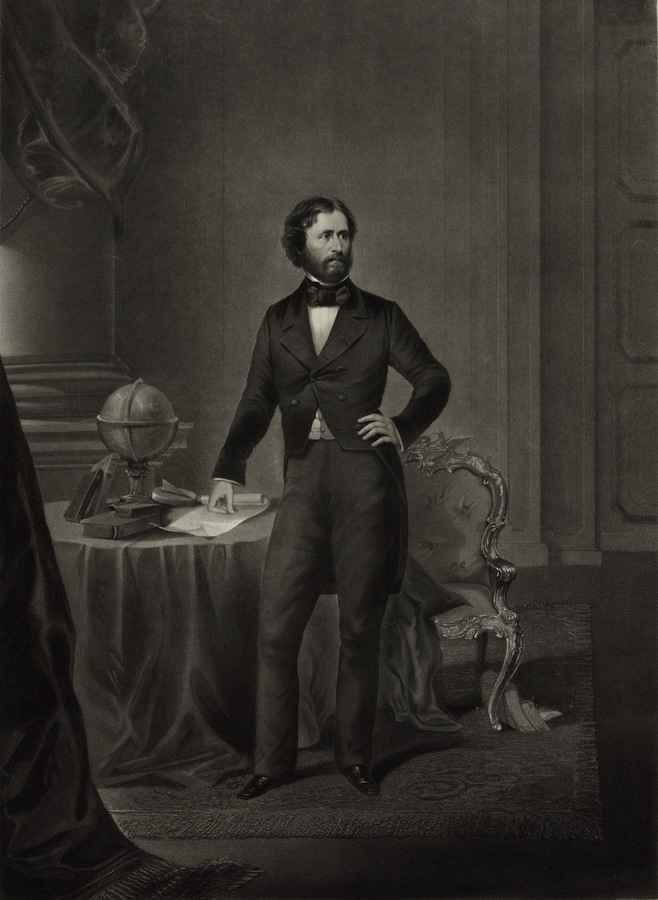

During this same period, the student body included John C. Fremont, one of the College’s most famous alumni, later known for his explorations of the American West and the settlement of California. Ironically, in 1856 he became the first presidential candidate of the antislavery Republican Party. Unlike most College alumni and some faculty who fought during the Civil War, Fremont served on the opposite side as a Union Army officer.

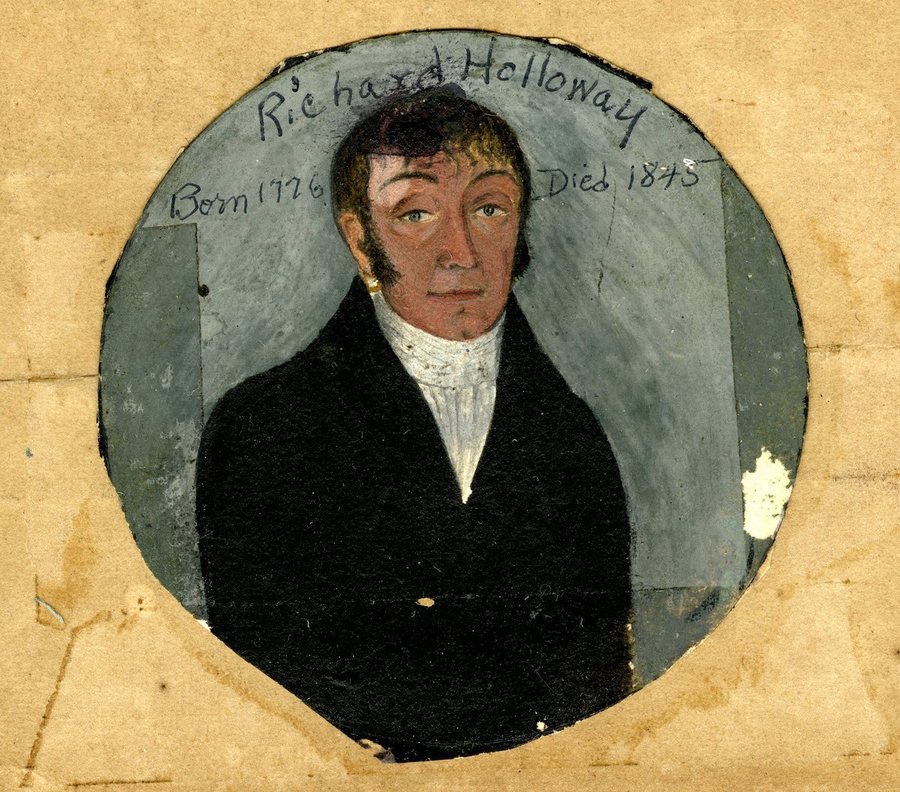

Randolph Hall is one of many campus buildings with important African American histories. In the antebellum period, many free blacks lived within the neighborhood adjacent to the campus. Some owned property here in the antebellum era; for example, in 1844, a free woman of color, Sally Johnson, purchased the house on 2 Green Way. It was passed down through her descendants until the College purchased it in the 1970s. James Holloway, a free person of color, owned five properties on College Street on property that would be the heart of campus. Another building was constructed during the Reconstruction era for A.O. Jones, an African American who was clerk of the South Carolina House of Representatives. In the modern period, the birthplace of Septima Clark, the civil rights era leader, is on our current campus, at 105 Wentworth St. Clark was educated at the segregated Avery Normal Institute, which now houses the College's Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture.

The Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston and the 250th Anniversary Historical Documentation Committee are committed to exploring these aspects of the College’s story. While preparing for our 250th anniversary celebration, the College joined the Universities Studying Slavery Consortium, a group of over fifty universities studying their historical relationships to slavery and its legacy of race related issues in contemporary life. Various offices, departments and programs at the College are now systematically exploring our history and the way it intersects with that of the city, the state and the nation.

The Center for the Study of Slavery is developing an African American heritage trail, beginning on the campus and extending into the surrounding neighborhood and city. The sites will be physically marked and digitally accessible. They will be incorporated into in-person tours for prospective students and other visitors. They’ll also be linked to other African American sites identified by other Charleston history and preservation-oriented organizations. A connection to the International African American Museum, slated to open at the end of 2021, will be especially important for our work. Our efforts will lead to a series of tours that will be posted on this website. The first tour for the 250th anniversary is only the beginning of this long-term project. We will continue to add to and refine the online tours as our research efforts yield new information.

On Jan. 30, 2020, President Andrew Hsu and the Historical Documentation Committee unveiled this new and unprecedented historical marker. In his speech that day, the president said, “I’m proud of this marker because it does not hide the faults of our past. On the contrary, it directly confronts our faults while still celebrating some of our key milestones.” We are also proud of that marker, the first of many in which we celebrate the “pride” of our achievements and unflinchingly confront the “pain” of our history. It is only in this spirit that we can fully embrace our motto for the 250th anniversary: History. Made. Here. and our eternal motto: Wisdom itself is Liberty.

Audio

Images