Morris Street Business District

Realtors, newer residents, and tourists in Charleston usually include the neighborhood around Morris Street in the Cannonborough-Elliottborough or Radcliffeborough subdivisions. To do so, however, erases Morris Street’s individuality and distinctive story.

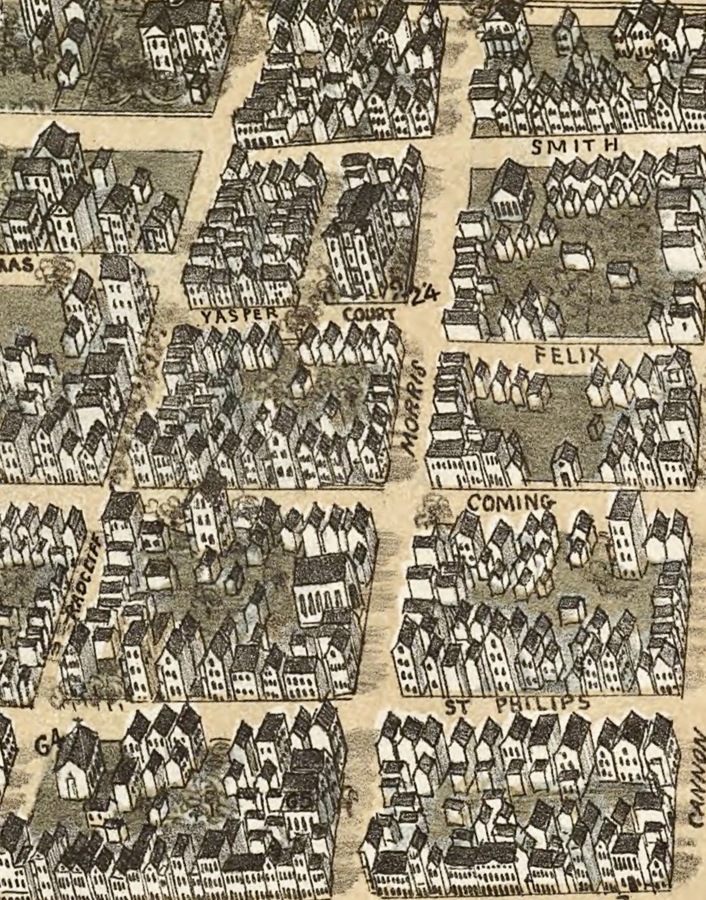

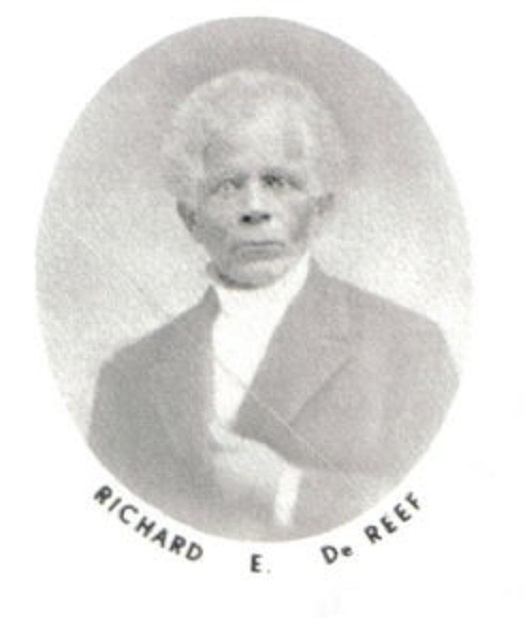

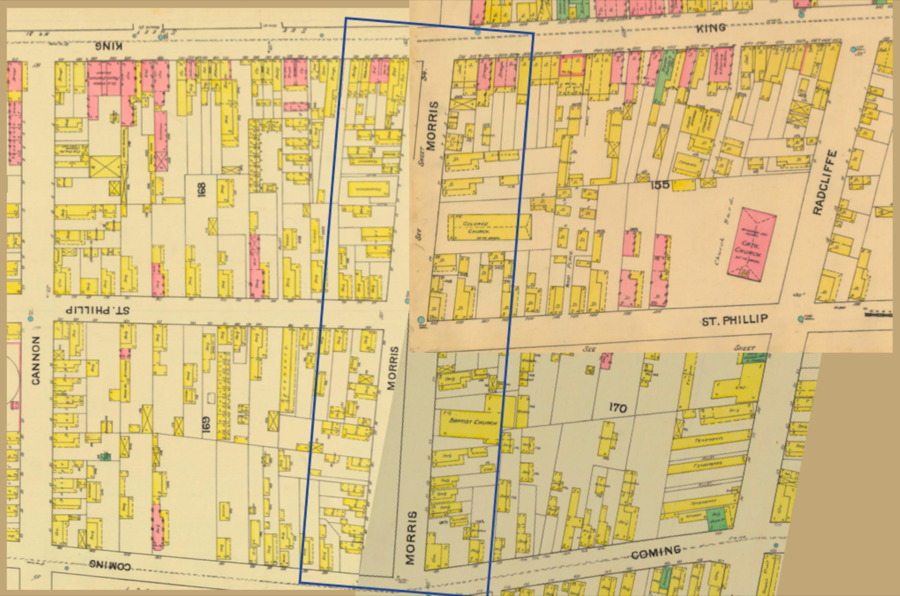

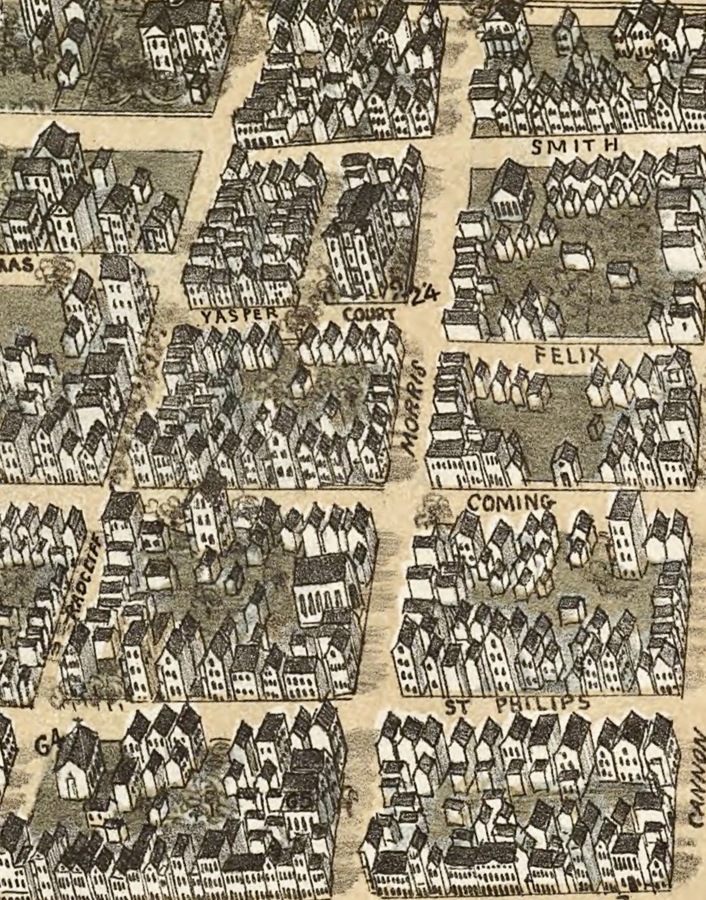

Realtors, newer residents, and tourists in Charleston usually include the neighborhood around Morris Street in the Cannonborough-Elliottborough or Radcliffeborough subdivisions. To do so, however, erases Morris Street’s individuality and distinctive story. Morris Street, bounded by King Street and Rutledge Avenue, has a unique history that illustrates resistance, vitality, and slavery’s legacies. Not only did a strong neighborhood and community develop along Morris Street, but the area also became an important business center for immigrants and African Americans. However, until the Antebellum era, the land that is today Morris Street was undeveloped and primarily used for agricultural purposes. In 1849, the Elliott-Morris family auctioned the land to brothers Joseph and Richard DeReef, two members of Charleston’s free African American population.

In the early 1850s, the DeReefs established a lumber factory, prompting the land’s urban development; the DeReef brothers created DeReef Court—a residential block bordering Morris Street—for African American lumber workers. The Morris Street neighborhood itself was relatively diverse with a population comprised of free and enslaved African Americans, working and middle-class whites (many of whom were recent immigrants from Europe), and some elite individuals, such as the DeReefs.

Morris Street represented an area of privacy and autonomy for many enslaved Charlestonians as the area developed into a neighborhood and community. By the Antebellum era, many cities relied upon a modified version of slavery that included the “hiring out” and “living out” systems. These systems allowed enslaved people to increase agency over their lives, sometimes to the extent of living away from enslavers and employers. As the hiring out and living out systems became more prolific, the neighborhoods where enslaved people lived grew.

The city of Charleston—and its many neighborhoods—were all impacted by the American Civil War. Immediate effects included the liberation of thousands of enslaved Charlestonians, some of whom would call Morris Street their home. People formerly enslaved in rural areas flocked to urban centers and, according to census records, over 37,000 people were enslaved in Charleston county alone. The Morris Street neighborhood swelled with the influx of formerly enslaved people, who added to the community along Morris Street.

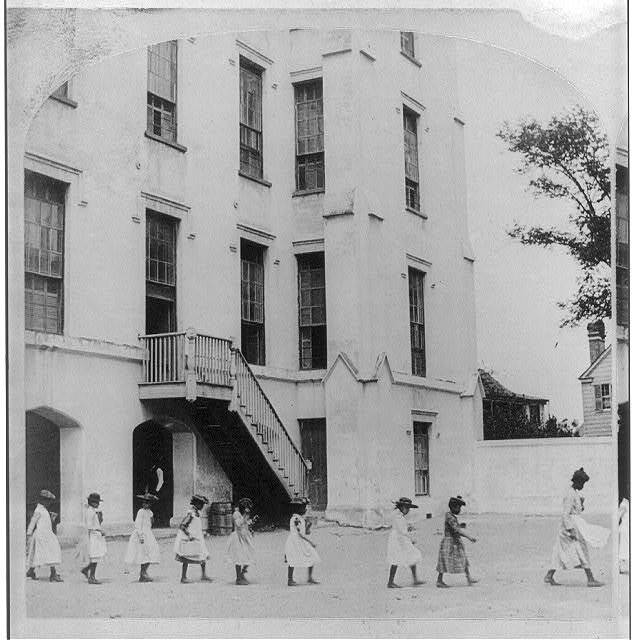

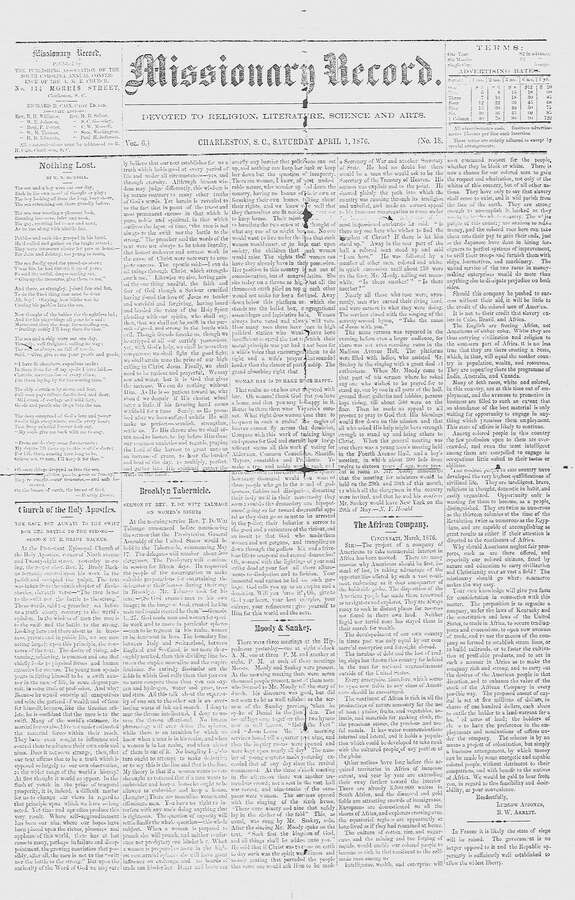

On Morris Street, new institutions represented some of the Reconstruction-era goals of the city’s Black population. For example, Freedman’s Bureau agents used buildings on Morris Street as offices and spaces to assist African American Charlestonians’ transition from slavery to freedom. The Freedman’s Bureau helped operate the Morris Street School (later renamed Simonton School), which opened specifically for African American children in 1865. The Missionary Record, an outspoken African American-owned newspaper, operated out of a building on Morris Street, publishing and circulating political, economic, and religious news for southern African Americans.

Many churches were also formally established following the end of the American Civil War. Previously, strict laws prevented free and enslaved African Americans from gathering in large groups and having religious services with no white supervision. Laws tightened following the 1822 attempt to liberate enslaved Charlestonians, which was led by Denmark Vesey. After this, white mobs destroyed some churches and Black congregations were forced to meet in secrecy throughout the Antebellum and Civil War years. However, beginning in 1865, African American churches reopened all over Charleston. Two churches—Morris Brown AME and First Baptist—still offer services and community assistance through food pantries on Morris Street.

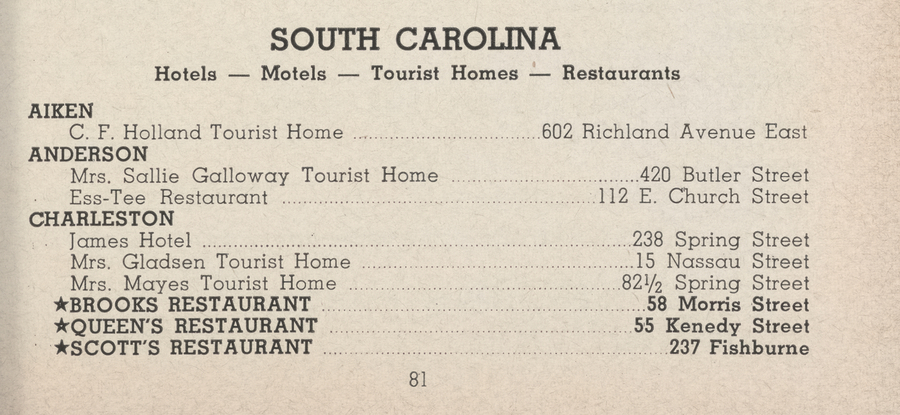

As Reconstruction ended and the restrictive Jim Crow era began, the Morris Street neighborhood was a beacon of African American community and resilience in a sea of white hostility and segregation. A variety of African American-owned businesses continued to thrive as the community strengthened. Barbershops, groceries, laundry services, and restaurants opened. Motels also made an appearance. The Brooks Motel and Restaurant (non-extant), once located at 56, 58, and 60 Morris Street, was an important stop for many African American tourists. The restaurant was featured in the Travelers’ Green Book, a travel guide for African Americans during the era of segregation, and was well-known in and outside of Charleston. The Brooks Motel gained even more recognition during Charleston’s civil rights movement when notable African American leaders—including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—stayed at the motel.

Morris Street’s twentieth century demographics followed the trends of the previous century. The neighborhood continued to consist primarily of African Americans, but a few immigrants also called Morris Street their home. During the nineteenth century, most of these individuals were from Western Europe. Some European immigrants and their descendants continued to live along Morris Street in the twentieth century, but their numbers shrank. Also, other immigrants from Eastern European and Asian countries accompanied Western Europeans. For example, Charlie Lum owned and operated “Chinese Laundries” at the corner of King and Morris Streets in the 1910s. However, due to segregation and white flight, the overall population of Morris Street was predominantly African American for much of the twentieth century.

Morris Street’s relatively diverse population became threatened as early as the 1970s by a different legacy of slavery: gentrification. Zoning laws forced many economic establishments out of business. Growing rent and property taxes are also culprits in heightening gentrification. Some may argue that gentrification is not a legacy of slavery but a way to “better” neighborhoods, eradicate crime, and increase an area’s wealth. This argument fails to see the full story. Gentrification is a tool used by white elites to continue to suppress historically Black neighborhoods and their residents. Anthropologist Shea Winsett argues that “gentrification is a threat to Black American economic survival [since] economic instability has historically been a way to marginalize Black Americans in society.” Morris Street’s identity as a African American and immigrant business district has been all but completely wiped away by late twentieth and twenty-first century gentrification practices.

Understanding the historical significance of Morris Street is important for a number of reasons. Its story reveals how African Americans in Charleston were able to resist slavery and its legacies during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through community and economic development. Buildings on Morris Street stand out as important sites of twentieth century civil rights organization. But the legacies of slavery continue to persist along Morris Street as gentrification ravages this historically important neighborhood and community.

Images