Cannon Street Hospital, 135 Cannon Street

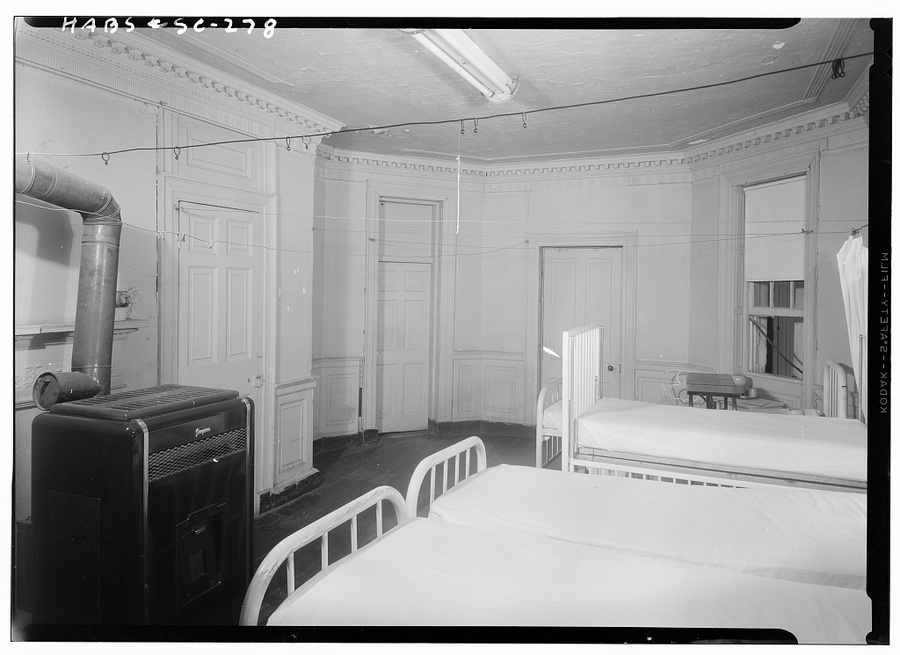

135 Cannon Street was home to one of the only African American hospitals in South Carolina during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Although it is no longer standing, Cannon Street Hospital, also known as the McClennan Hospital, is an important site of African American history. The hospital was originally named after its founder, Dr. Alonzo Clifton McClennan (1855-1912). Dr. McClennan was one of the first Black doctors in Charleston. He saw the need for such a facility due to segregation laws that barred Black doctors and nurses from seeing patients in white hospitals. The charter for the hospital was approved in 1897 by the City of Charleston. That same year, the building was privately purchased for $4,500 and it hosted twenty-four beds, nurses' dormitories, a dining hall, an operating room, a reception area, and an office space. The original hospital was razed in 1961.

Oral histories provide historians a glimpse into the lives of Black residents during Jim Crow in Charleston, South Carolina. A longtime Charleston resident, Anne Marie Gilliard (b. 1928), discussed her experiences of going to the Cannon Street Hospital when she was a young girl. She was a frequent visitor because of her sister's various illnesses. Every day, people crowded into the hospital to wait to be seen, similar to a modern walk-in clinic. As a result of segregation laws, African American patients came from as far as Awendaw, Mount Pleasant, Edisto, and Daniel Island because of the preponderance of both "whites-only" and segregated hospitals throughout the state. Though the hospital was considerably "old and run down", Anne Marie Gilliard preferred Cannon Street Hospital to other area hospitals that admitted African American patients such as Roper Hospital because Roper "treated poor black folk like lepers". Her description of the doctors and nurses at Cannon Street Hospital is telling:

The nurses at Cannon Street Hospital seemed to care . . . The doctors were very nice, too. There were plenty of people who couldn't pay either. My father used to bring fruit to pay the bill, and they took it. I don't know, it just felt like, I guess, you know, to be in a place where you were among your own, and they treat you like a person.

One of the doctors that Anne Marie Gilliard used to go and see at the facility was Dr. McFall, the first African American appointed to the South Carolina State Hospital Advisory Council to the State Board of Health in 1949. In 1956, the city began to discuss moving the hospital and modernizing it by merging it with the Medical College of South Carolina, Roper Hospital, the Tuberculosis Sanitorium, the Medical College Teaching Hospital, and St. Francis Xavier Hospital. These changes intended to add up to fifty beds to Cannon Street Hospital. The facility was replaced by then-new "McClennan-Banks Negro Hospital".

Another example of how precious oral histories are to the preservation of history of sites like Cannon Street Hospital is that of Norma Hoffman Davis. Her father was Dr. Joseph Irvin Hoffman, an Avery Institute graduate who attended Howard University. After graduation, Dr. Hoffman attended Meharry Medical College in Nashville for medical school. Once finished, he had an internship in Washington state, and then returned to Charleston in 1929. Norma's story about her father is unique because she also discusses the role of religious and spiritual beliefs held by members of the Gullah community in Charleston. She remembered her father talking about patients who believed they had been cursed, and in order to convince them to try conventional medicine, he listened to their stories and respected their beliefs. The relationship between Dr. Hoffman and his patients opened a door to trust, which rarely existed between Black patients and white doctors.

It is understandable that people of color had a serious mistrust of the white establishment and medical system, particularly in the South. The history of racial violence and enslavement of African Americans, combined with medical experiments done without consent, is a dark legacy that historians continue to uncover today. Some aspects of contemporary medical practices have roots in the antebellum period when certain doctors experimented on enslaved people, experiments that often resulted in death. In order to understand the discrimination that people of color faced in medical practices at the end of slavery and throughout the Jim Crow period, one must view it in a broader historical context.

A white gynecologist by the name of J. Marion Sims, who began his education at the Medical University of South Carolina in 1833, invented the vaginal speculum - a tool that is used to open the walls of the vagina. However, there is ample evidence of Sims' barbaric treatment of enslaved women while seeking to cure vesicovaginal fistulas. J. Marion Sims "acquired" eleven enslaved women who suffered persistent vesicovaginal fistulas, repeatedly operating on them over the next three years. Some of these women endured as many as thirty surgeries individually. While many scholars throughout early-American history have praised Sims' efforts because of the need to find a cure for such a horrific condition, more scholars today insist that the women Sims used in his procedures were nothing more than guinea pigs who were not allowed to give legal consent due to their status as enslaved women. Furthermore, his choice not to use anesthesia for his procedures on these women is the most controversial aspect of his horrendous practices.

Mistreatment, malpractice, and discrimination towards people of color throughout the nineteenth century persisted in the medical field during the twentieth century. This legacy of slavery can be connected to the oral histories of Black patients in Charleston over the years. Former patients like Norma Hoffman Davis illustrate the significance the Cannon Street Hospital held for Black Charlestonians during the early twentieth century when she explained that people of color only had two choices: Roper, in the segregated section where the white nurses and doctors often dismissed their Black patients' grievances as a result of negligent malpractice; or Cannon Street, where people gave the best treatment they could, but the facilities were "dirty and old" as a result of lack of resources. Sometimes patients chose neither option; Norma's mother decided to give birth to her at home because of both of these reasons.

The fact that Cannon Street Hospital was privately owned and operated and received a clientele that was gravely underprivileged in Charleston explains why the facilities did not have the amenities that Roper could boast about in the early twentieth century. Anne Marie Gilliard's oral history about how patients would trade goods for the doctors' services is direct evidence of the underfunding of Black medical care. Additionally, there were long lines outside of the hospital until closing hour each day. What is known about Cannon Street Hospital and the experience of Black Charlestonian patients during the Jim Crow era allows historians to pursue research that sheds light on the relationships between African Americans and modern practices, which is fundamental to understanding how to create a more equitable system in the twenty-first century.

Images