East Side Neighborhood

The neighborhood known today as the East Side has a complex history that dates back to the 1760s and intertwines the stories of Black and white Charlestonians, working- and upper-class citizens, and a variety of different communities.

The neighborhood known today as the East Side has a complex history that dates back to the 1760s and intertwines the stories of Black and white Charlestonians, working- and upper-class citizens, and a variety of different communities. The creation of this neighborhood was directly linked to the institution of slavery, and its history continued to be impacted by the legacies of slavery. Even today, East Side residents resist twenty-first manifestations of slavery’s legacies. To understand how this neighborhood developed and the threats it currently faces, we must first go back to the neighborhood’s establishment.

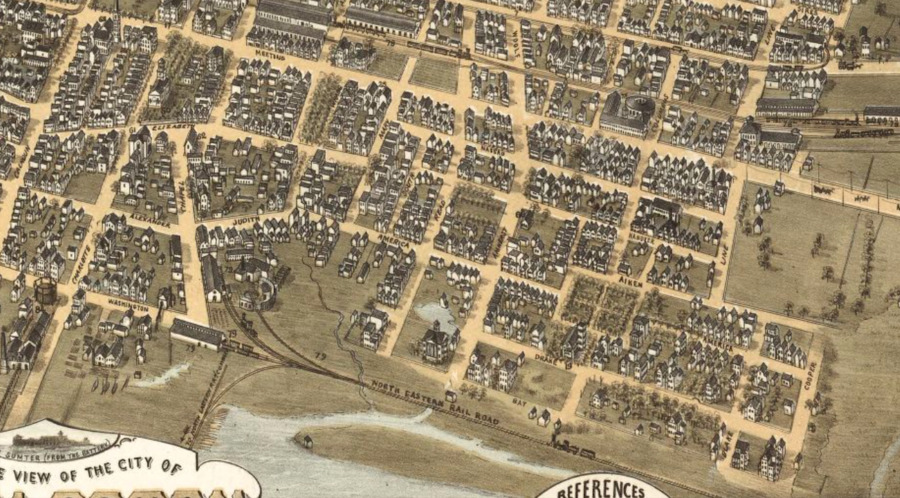

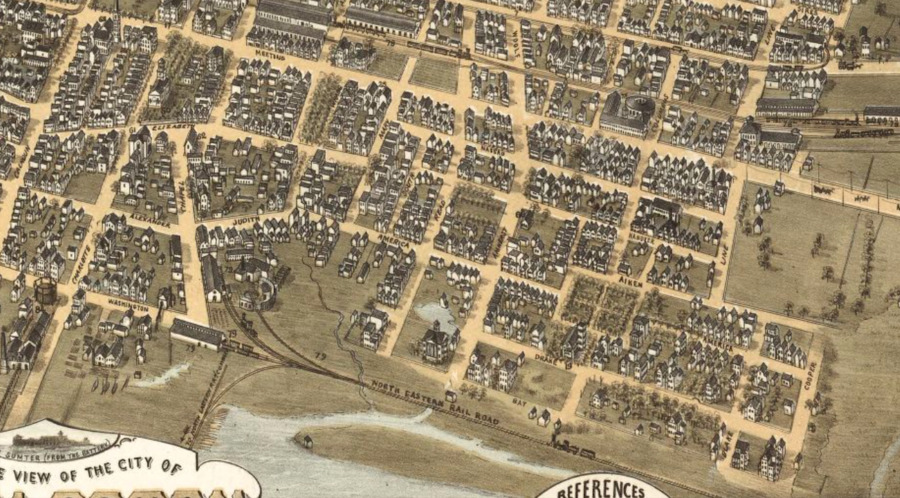

In 1769, Henry Laurens purchased undeveloped land on the outskirts of Charleston and created plans for a neighborhood he called “Hampstead Village.” Laurens’s partnership in a large slave trading corporation allowed him to amass the wealth required to make this purchase. Laurens advertised Hampstead Village as a wealthy suburb of Charleston where elites could enjoy waterfront properties along the Cooper River and public green spaces. Laurens and other shareholders attempted to entice other white elites—enslavers, elite merchants, and members of the slave trade—into buying lots in Hampstead Village, describing the neighborhood as “a Retreat either for a Gentleman or Merchant.”

Hampstead Square’s development was quickly halted by the onset of the American Revolution (1775-1783). During the war, the neighborhood was destroyed and then rebuilt as a less elite and more diverse suburb. Only a few decades later, the neighborhood found itself in chaos once again. Anxieties grew as the War of 1812 swept through the United States. The British Navy targeted important ports and harbors in northern cities like Boston. Charleston residents, especially those in the waterfront neighborhood of Hampstead Village, felt they would soon be under attack. Many Hampstead residents abandoned the neighborhood as the city built fortifications to prepare for fighting.

In the years following the War of 1812, the neighborhood underwent a demographic change as the East Side increasingly became an area of privacy and autonomy for many enslaved Charlestonians. By the Antebellum era, many cities relied upon a modified version of slavery that included the “hiring out” and “living out” systems. These systems allowed enslaved people to increase agency over their lives, sometimes to the extent of living away from enslavers and employers. As the hiring out and living out systems became more prolific, the neighborhoods where enslaved people lived also grew.

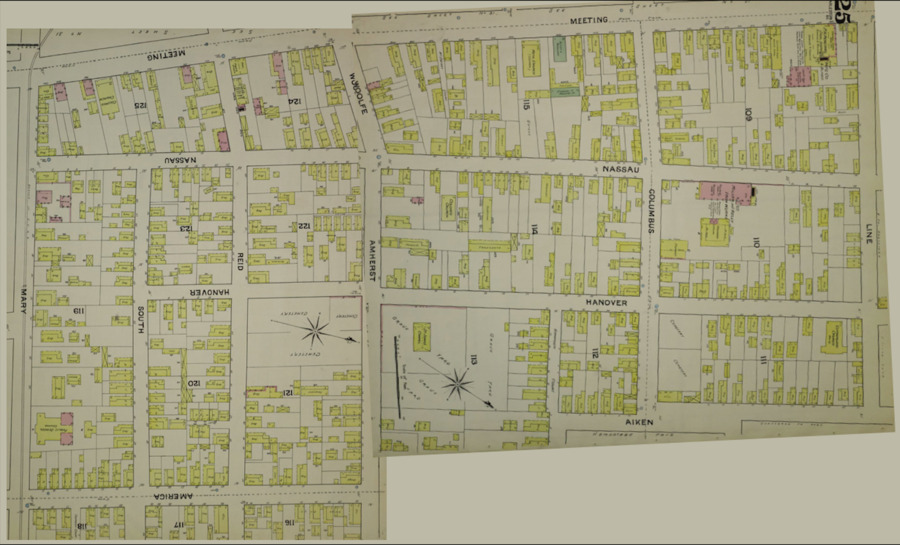

As its population changed, the East Side itself changed. The city of Charleston viewed the East Side as an undesirable subdivision and relocated the city’s incinerator and dump to the neighborhood. Railroad depots were established around the East Side, covering the area in a haze of smoke. The establishment of industry in the East Side with the opening of a cotton factory in 1848 further contributed to pollution. The factory almost immediately closed, and the city used the building to house Charleston’s destitute population, only reifying the city’s perception of the East Side as an undesirable eyesore. This perception was undoubtedly intertwined with white government officials’ racial biases.

The city of Charleston—and its many neighborhoods—were all impacted by the American Civil War (1861-1865). Immediate effects included the liberation of thousands of enslaved Charlestonians, some of whom would call the East Side their home. People formerly enslaved in rural areas flocked to urban centers joining, according to census records, over 37,000 people who had been enslaved in Charleston County alone. Neighborhoods that had housed enslaved people during the period of the living out system in the Antebellum era grew with the influx of formerly enslaved people who sought the safety and community of these neighborhoods. Following the Civil War, the East Side experienced a demographic seachange. Although considered predominantly white at its founding, in 1960, a majority of its residents were Black, and in 1980, 95% of the residents were African American. With a larger population came more development. Churches, businesses, education centers, and other establishments that catered to the Black community continued to open in the East Side.

Throughout the twentieth century, the legacies of slavery impacted African American East Side residents. The neighborhood’s predominately Black population stirred white anxieties. Police profiling and violence against African Americans dramatically increased, leading to brutality and the death of civilians. The city of Charleston neglected to supply adequate municipal services to the East Side’s predominantly Black residents. The legacies of slavery also combined with environmental issues, leading to massive flooding concerns in this waterfront neighborhood.

The twenty-first century poses new threats that tie back to the legacies of slavery. The rising gentrification of this area has pushed out individuals, families, and businesses that have called the East Side home for generations. Some may argue that gentrification is not a legacy of slavery but a way to “better” neighborhoods, eradicate crime, and increase an area’s wealth. This argument fails to see the full story. Gentrification is a tool used by white elites to continue to suppress historically Black neighborhoods and their residents. The College of Charleston’s Race and Social Justice Initiative argues that “gentrification is rooted in the history of segregation, redlining, suburbanization urban renewal programs, and redevelopment schemes…that kept Black people stranded in concentrated poverty with few job prospects.” Therefore, the East Side’s economy and community are both threatened by gentrification.

The East Side’s history reveals how Black Charlestonians have faced and fought against slavery and its legacies by forming community and demonstrating resistance. The future of the East Side is uncertain as gentrification continues to increase. However, there are still a number of businesses, churches, and other important places in the East Side today. Some trace their history back to the 1800s while others opened more recently. However, all of the places in the following list have important similarities. The following East Side establishments represent unity, Black entrepreneurship, and community aid:

- Hannibal’s Kitchen

- Fair Deal Grocery/The Spot 47

- Mary’s Sweet Shop

- Knight’s Super Market

- Laundry Matters

- Top of the Line Barbershop

- The Charleston Branch NAACP

- Phillip Simmons Museum Home and Workshop

- Eastside Community Development Corporation

- St. Barnabas Lutheran Church

- St. Luke’s Reformed Episcopal Church

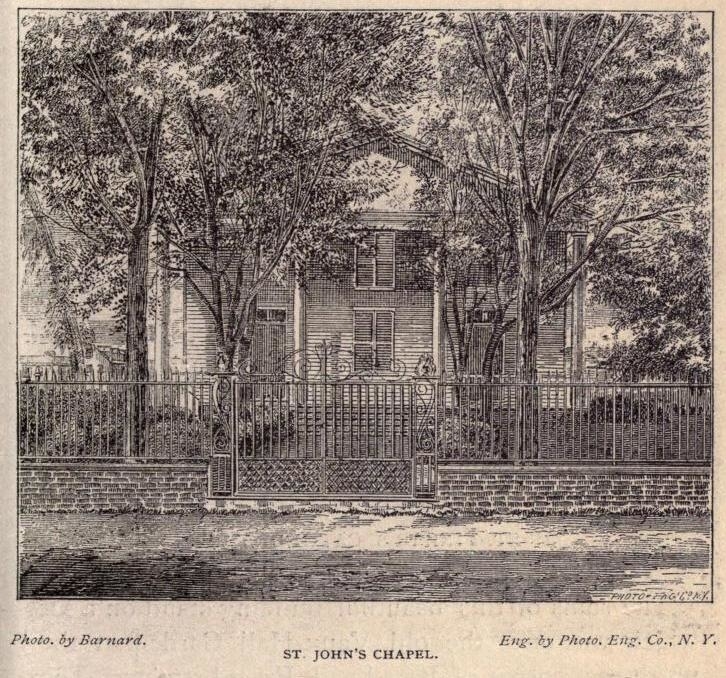

- St. John’s Episcopal Chapel

- Vanderhorst Memorial Christian Methodist Episcopal Church

- Ebenezer African Episcopal Church

Images