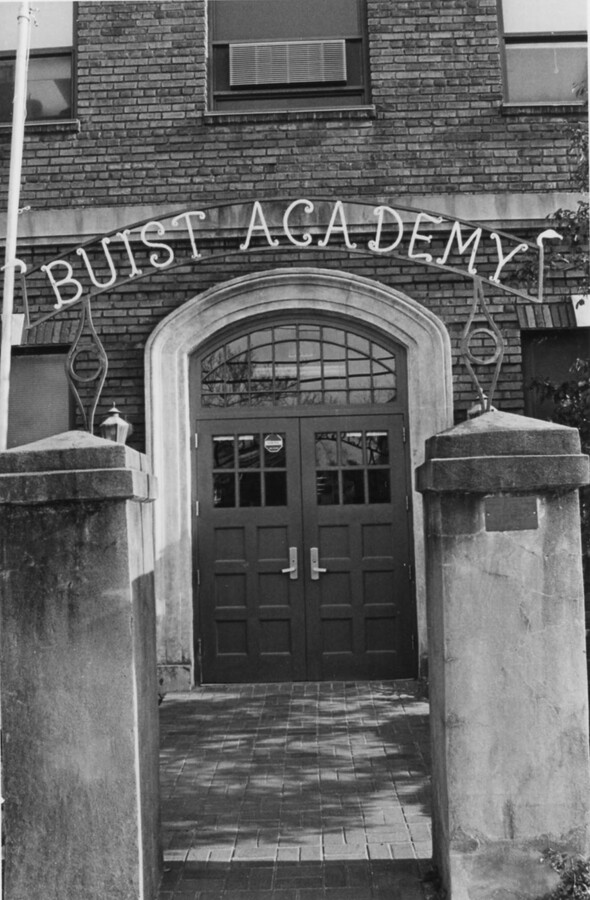

Buist Elementary School, 103 Calhoun Street

Buist Elementary School, a segregated school for Blacks, was located at 103 Calhoun Street in Charleston, South Carolina. It is now known as Buist Academy for Advanced Studies and is an academic magnet school

Buist Elementary School, a segregated school for Blacks, was located at 103 Calhoun Street in Charleston, South Carolina. It is now known as Buist Academy for Advanced Studies and is an academic magnet school. The school's history is rife with racial disparities, conditions that persist today.

The school was constructed in 1920 and opened in 1921. As noted, the school was an all-Black institution during the era of segregation; the entire staff and student body were African American. During the era of Jim Crow, the inadequate resource allocation for schools for Black youth resulted in overcrowding and a lack of standard quality school supplies. For example, in 1942, Buist Elementary held 1,073 students even though the maximum capacity was supposed to be 420 students. Furthermore, the school was deteriorating due to neglect from the Charleston County School District. In this way, Buist Elementary was the product of inadequate resources allocated for Black schools in the United States on a systemic level.

In 1950, Black parents in rural Clarendon County (SC) filed a lawsuit to demand equal school facilities, which was one the cases that was a part of the historic Supreme Court decision, Brown vs Board of Education. As a result, South Carolina as well as other states in the South tried to undertake projects to “equalize” the schools that served Black students as a way to slow down desegregation efforts. However, in 1954, the landmark decision was read and determined that state laws mandating racial segregation in public schools were unconstitutional. One can see the "separate but equal" status in schools such as Buist after the landmark decision was made. A lack of allocated resources to the school from Charleston County was a byproduct of this. A former student of Buist, Leonard Taylor, described the neglect of Charleston County as such:

I think we got all second-handed everything back then – second-handed schools, second-handed books, and whatever, and I think black people for some reason or other really got shortchanged.

One can read an oral history such as this and conclude that an equal education was not accessible to people of color. Buist Elementary has always been evidence of this. The importance of an equally funded school program for Black children was ignored by Charleston County.

Aside from the limited school supplies, another former student discussed the student-to-teacher ratio as a symptom of the district's underfunding. Lillian Green (1934) recalled that students went to school in shifts during this period in order to decrease the student-to-teacher ratio. Classes were taught in one shift from 7:00 in the morning until 12:30 in the afternoon, and then another shift from 1:00 in the afternoon until around 6:00 in the evening. Another issue with being a Black child in a segregated system was the humiliation one endured when walking to school. Green remembered her own experiences with this, having to take St. Philip Street or Meeting Street over to Calhoun Street because, as she recalled, African Americans were not allowed to walk on sections of King Street except on Sundays when the shops were closed. Freedom of movement is something that Americans take for granted, but it was denied to Black citizens for decades during the Jim Crow era.

The limited school supplies, lack of individual attention, and convoluted trips to school were obstacles that blocked equal education for young Black children in Charleston. Once the school transformed into the academic magnet school, some of that changed into more subtle forms of discrimination.

Created in 1985, Buist Academy Academic Magnet Elementary School was developed to attract white students to the all-Black Charleston District 20. After this change, Lillian, a nurse who was involved in the historic Charleston Hospital Workers Strike of 1969, explained that, "you could hardly get a Black kid into Buist School still because now it's Buist Academy.” The transition of Buist Elementary School to Buist Academy improved the school, but now for white students rather than Black ones.

Eventually, Federal court orders mandated Charleston County School District to comply with desegregation laws. However, in 2002, white Buist Academy parents filed a lawsuit to force the school district to eliminate the racial quotas that were created in 1998 to reintegrate the school. As a result of the suit, by 2016, less than 5% of students at Buist Academy were Black. According to civil rights expert, Elise Boddie, this is an example of "adaptive discrimination" - discrimination adapting to modern legal limits and laws set in place. Though modern constitutional law shifted after Brown v. Board of Education, adaptive strategies used by government officials include discriminatory structures to limit equal access to education, such as school privatization and "freedom of choice" plans that perpetuate segregation by giving whites priority at well-resourced institutions and schools such as Buist Academy.

Images