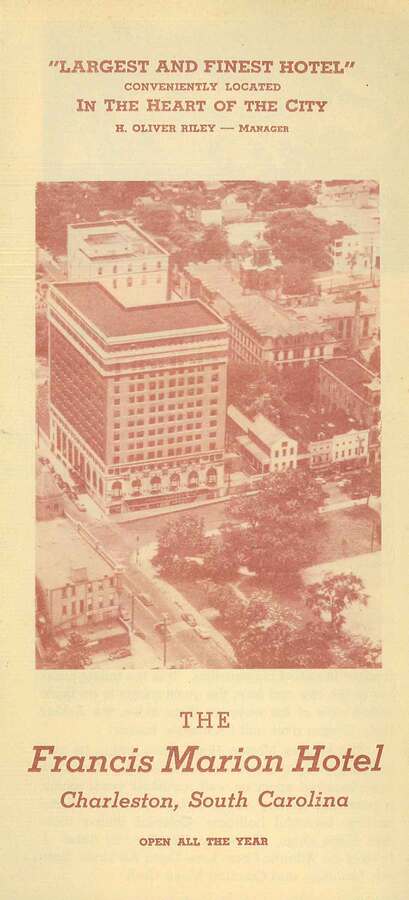

Francis Marion Hotel, 387 King Street

The Francis Marion Hotel presents another story of how Black Charlestonians fought against the legacy of slavery and white supremacy in their effort to establish a more equal Charleston and a more equal America.

The Francis Marion Hotel presents another story of how Black Charlestonians fought against the legacy of slavery and white supremacy in their effort to establish a more equal Charleston and a more equal America. Built during the era of segregation, the hotel joined other businesses in becoming a target of civil rights demonstrations that eventually forced the city’s Retail Merchants’ Association to lift their segregated store policies.

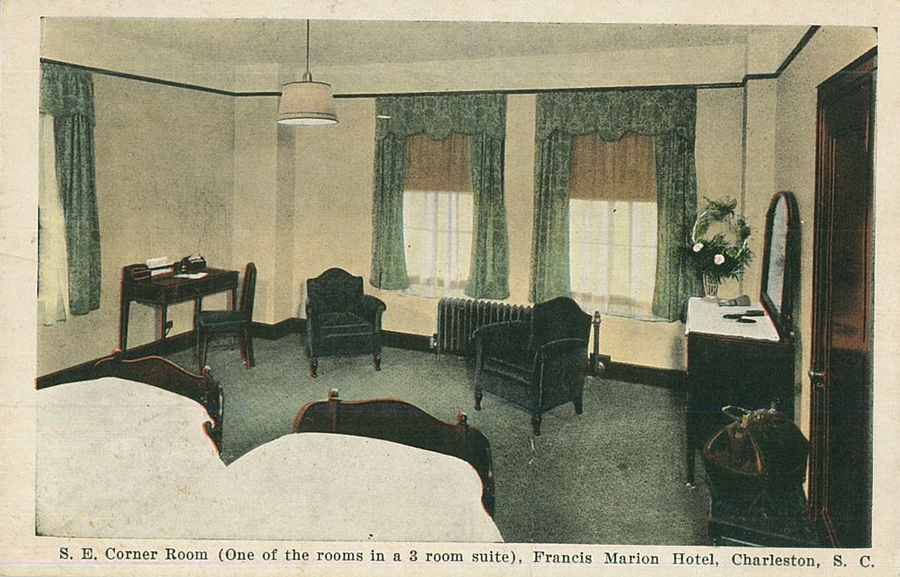

Built in 1924 across from Marion Square, the Francis Marion Hotel has been a Charleston landmark since its construction. The stately building, however, has a dark past—as many do in Charleston. The African Americans who helped build it—people like Harley Cunningham—were not permitted to stay in the hotel. Because of this, it would become another site where the Black community stood against racial oppression in the 1960’s, right in the backyard of the College of Charleston.

From its inception, as with S.H. Kress and many other businesses on King Street, the Francis Marion did not serve people of color. Even Black Americans who had achieved notable fame, including Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson, were unable to stay at the Francis Marion, or “any really nice hotels,” according to Norma Hoffman-Davis, a local resident. When they visited the city, they sometimes had to board with Black Charlestonians. For the Black community, it was a slap in the face that even nationally famous African Americans were unable to stay at hotels like the Francis Marion, relegating even powerful and wealthy citizens to secondary status.

This status quo would eventually change. The catalyst for this, just as with the Kress store, was the student-led sit-in at the Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina during the winter of 1960. The sit-in movement spread to Charleston in 1960 under James Baker, a leader of the youth chapter of the NAACP. James Baker’s planned Woolworth's protests spontaneously pivoted to the Kress building’s lunch counter. In these protests, Black Charlestonians engaged in direct action against white supremacy, standing up and demanding an equal place in Charleston.

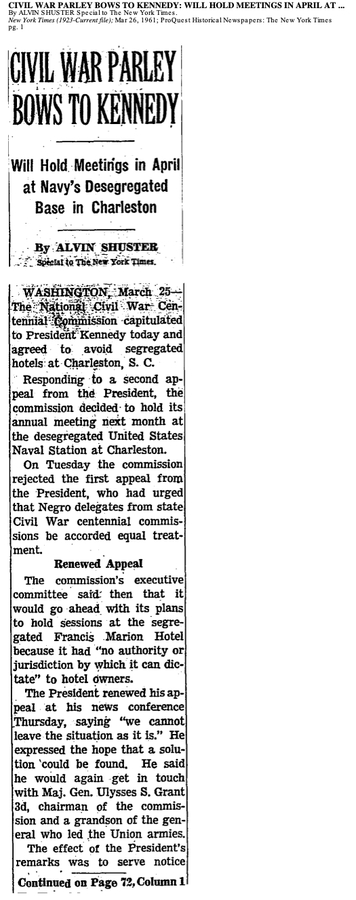

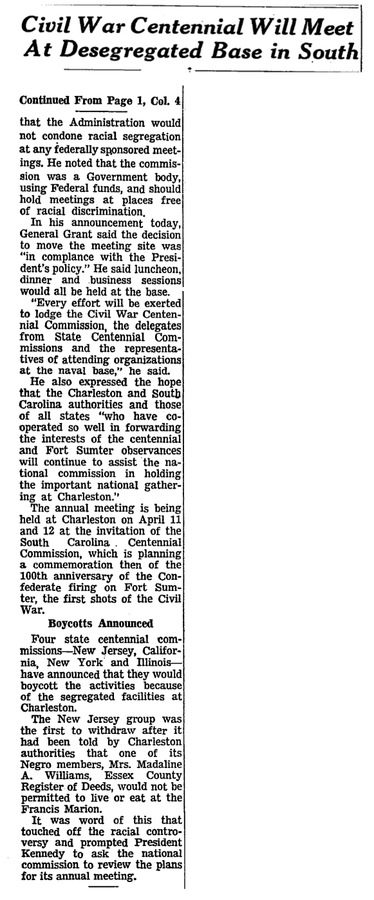

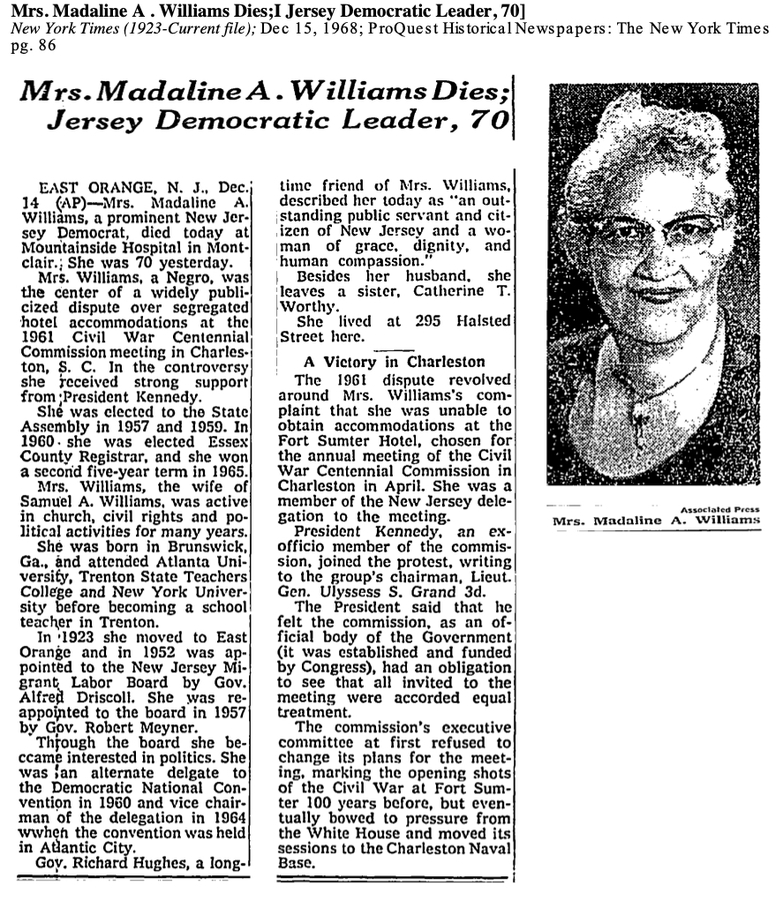

In the midst of this movement was the centennial commemoration of the Battle of Fort Sumter and the beginning of the Civil War. The United States Civil War Centennial Commission planned to commemorate the centenary of the Civil War with a commission from each state, and the Commission accepted an invitation by the South Carolina branch to meet at the Francis Marion. It intended to stress “reconciliation, shared unity, and shared honor.” One of the major obstacles to this, however, was the policy of segregation. This was because one of the members of the New Jersey commission, Madaline Williams, was Black. She was therefore not allowed to stay in the Francis Marion, and had to find lodging elsewhere. By the early 1960s, however, this refusal would not go quietly unnoticed.

Madeline Williams herself was familiar with breaking barriers, being the first Black woman elected to the state legislature of New Jersey as well as an “executive member of her local NAACP branch.” She and the director of the New Jersey Centennial Commission requested that the meeting be moved to “a location which will respect the fundamental Constitutional rights of persons of all races.” This activism even prompted Governor Ernest F. Hollings of South Carolina to accuse Williams of being an agitator, sent to rub in the Civil War defeat. However, the message was plain: not only was the Black community of the city itself fighting segregation on King Street, but also so was the rest of the country.

Such pressure meant segregation couldn’t last on King Street. Some of the first cracks were showing when, in June 1963, the King Street locations of S.H. Kress, Woolworth’s, and W.T. Grant began desegregating their facilities. By July, this had expanded to over ninety merchants on King Street who bowed to the immense national and state pressure to desegregate. While far from the last legacies of slavery to be demolished, this was the death knell for legal segregation in Charleston.

Images