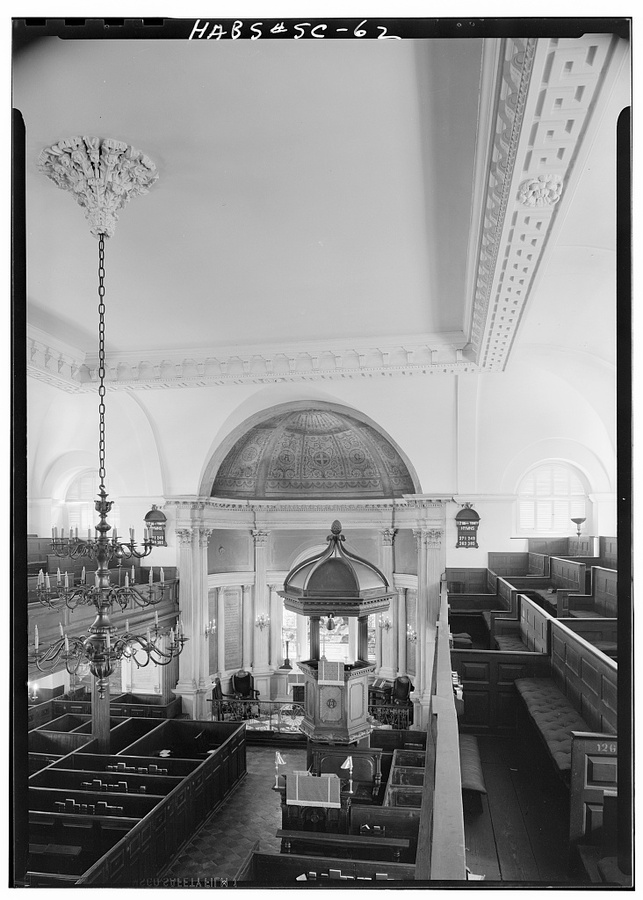

St. Michael’s Church, 80 Meeting Street

An Injustice on the Four Corners of Law

When Anglicanism was made the official religion of the Carolina Colony in 1703, only one parish was established in the city of Charleston: St. Philip’s. Less than fifty years later, the building became too small to adequately serve the numbers wishing to worship there, leading citizens to petition for the division of the parish.

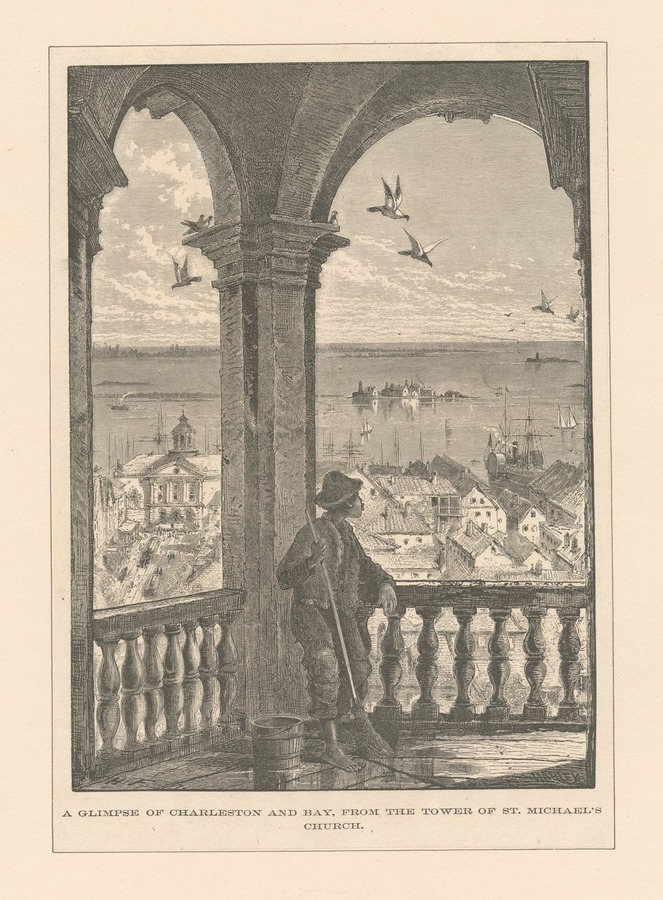

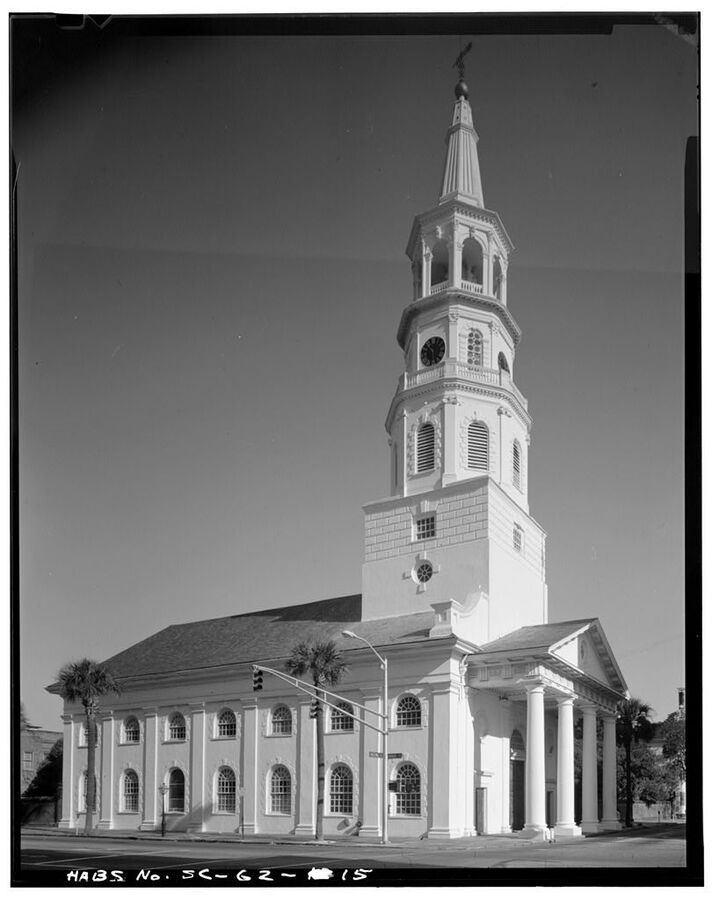

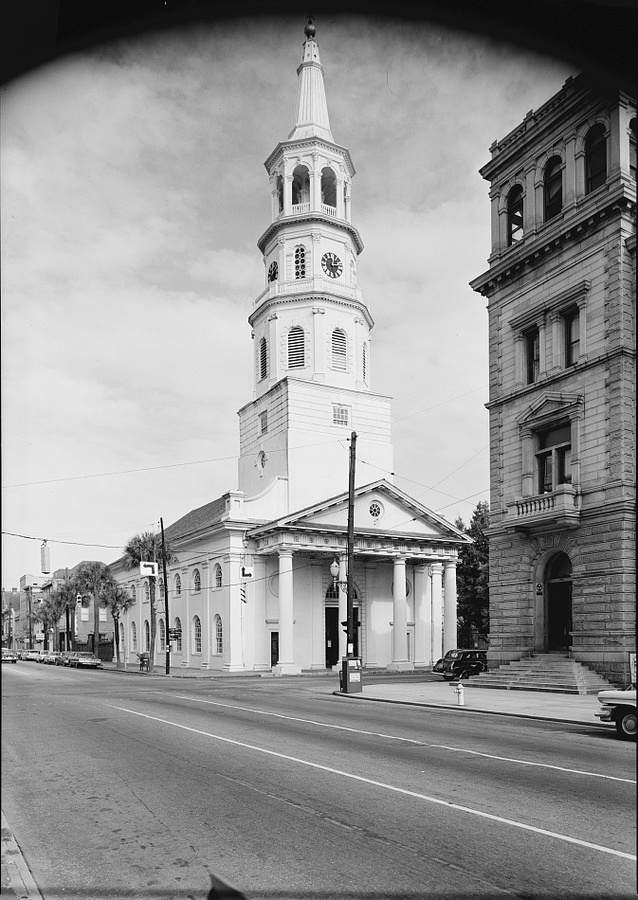

When Anglicanism was made the official religion of the Carolina Colony in 1703, only one parish was established in the city of Charleston: St. Philip’s. Less than fifty years later, the building became too small to adequately serve the numbers wishing to worship there, leading citizens to petition for the division of the parish. In June of 1751, the parish of St. Michael was established, and work quickly began on the construction of a new church.

Many of the skilled and unskilled laborers on pre-1865 construction projects in Charleston were enslaved. Due to the scarcity of primary sources, details about most of the building projects have been lost to time. St. Michael’s Church, however, is a rare exception. Still, those records were almost unknown until the South Carolina Historical Society conserved them in 2003.

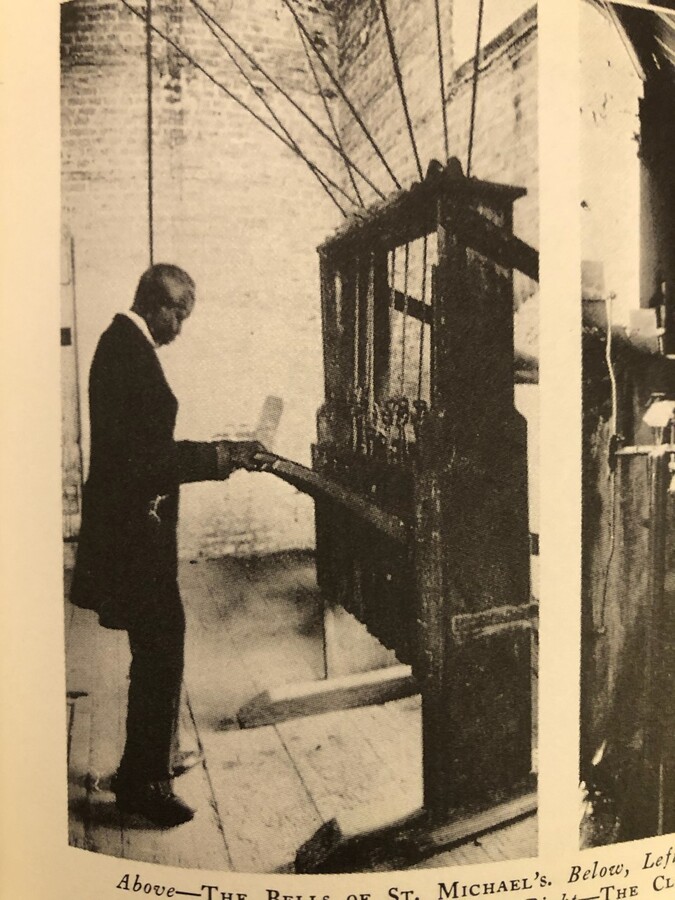

From the records, we learn that between October 1752 and November 1754, Samuel Prioleau Jr., secretary of the Commissioners to Build a New Church at Charles Town, kept track of the names of enslaved laborers and their owners. The purpose of his careful accounting was to enable him to pay owners for the work of their enslaved laborers he hired to build the church—a common practice referred to as hiring out. Southerners would hire the labor of the enslaved from their masters for seasonal or short term projects (like construction) or to supplement their enslaved labor force (typically at harvest time). Private individuals, churches, and the government used this system to acquire the labor required for a variety of projects without investing in purchasing slaves. Urban enslaved people who were hired out often lived in a state of quasi-freedom that angered many southern whites and undermined the slave system. The enslaved people who participated in the system took full advantage of the benefits of hiring out. Frederick Douglass, for instance, noted how he and others used it as a way to escape slavery. When they were allowed to keep some of the money they earned, they used it to buy their freedom. The hiring out system did not apply to just men; at least one woman is listed on the tally sheets for St. Michael’s.

The white workers and craftsmen hired to build the church likely had enslaved assistants or supervised the work of highly trained enslaved artisans and craftsmen. In Charleston, manual labor was often seen as work that was only to be done by the enslaved. In urban areas, this included construction and also more detailed work such as carving, plastering, and other decorative work.

The role of enslaved and free Blacks in the history of St. Michael’s stretches beyond the construction of the church. Many owners required the people they enslaved to attend church with them. The enslaved congregants would watch the services from the gallery or in a segregated seating area. By attending St. Michael’s with their masters, the enslaved were hearing scripture interpreted in a way that told them honoring their masters was their highest service to God. Owners, however, could not monitor the conversations engaged in before and after services in these churches.

The records kept at St. Michael’s and others reveal even more about the religious lives of those who attended. For instance, some contain the names of those who received private communion because they could not participate in regular services. It is noted in those records that “servants” received private communion as well. Black children also attended the Sunday School. These were likely the children of free Blacks since laws prohibited the education of enslaved people.

After emancipation, the role of Black congregants in white churches was hotly debated. Some Blacks chose to attend all-Black congregations. In contrast, others were forced to leave or denied membership in churches they had attended prior to emancipation. By 1870, only two Black people were eligible to participate in communion at St. Michael’s, and in 1908 the last was buried in the cemetery purchased by the parish for the express purpose of burying the Black members of the congregation. The leaders of St. Michael’s accepted Blacks as members, but when Blacks made an attempt to participate in the Diocese Convention in 1888, St. Michael’s denied them this opportunity. The church would not send Black representatives until the leadership changed in 1895.

St. Michael’s location on the corner of Broad and Meeting Streets makes it one of Charleston’s iconic Four Corners of Law. Despite the site's loose association with justice, the people who constructed the church building were denied their own freedom and justice. But, they were not nameless. From Samuel Prioleau Jr.’s careful accounting of the labor of enslaved people hired to build the church’s walls, we know who they were; we can find their descendants. Those names provide the content for a potential memorial that would finally give them some measure of recognition for the work they performed in building the cultural landscape of historic Charleston.

Images