Charleston Branch of the NAACP, 81-A Columbus Street

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was originally founded in 1909.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was originally founded in 1909. Through its quarterly magazine The Crisis, this organization pursued a civil rights agenda that included, organizing labor campaigns and hosting vocational training workshops for Black workers; pressuring the federal government to pass anti-lynching legislation; financing legal challenges to discrimination in employment; and providing education across the nation. Community-oriented local chapters were especially important to this organization and were largely where most of the organizing took place.

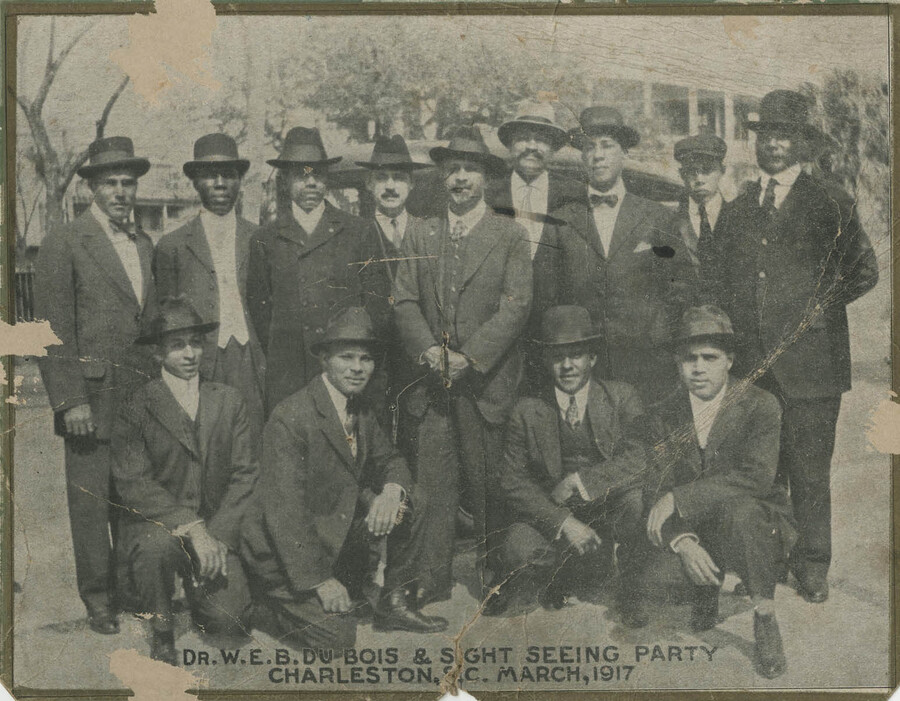

The founder of the Charleston branch of the NAACP, Edwin “Teddy” A. Harleston, was a man of many talents. After having graduated from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts with a specialty in painting, he returned to his hometown of Charleston in 1913. He also proved his political bonafides by organizing the local NAACP branch on February 23, 1917. In fact, shortly thereafter none other than one of the original co-founders of the national organization, W.E.B. Du Bois, visited the city of Charleston and encouraged members to strive towards self-improvement and civil rights. Championing the same ideals and aspirations of the national organization, the local branch cooperated extensively with Local 1422 of the International Longshoreman’s Association —an exclusively African American labor union in the city—and challenged segregation in workplaces and educational institutions throughout the city.

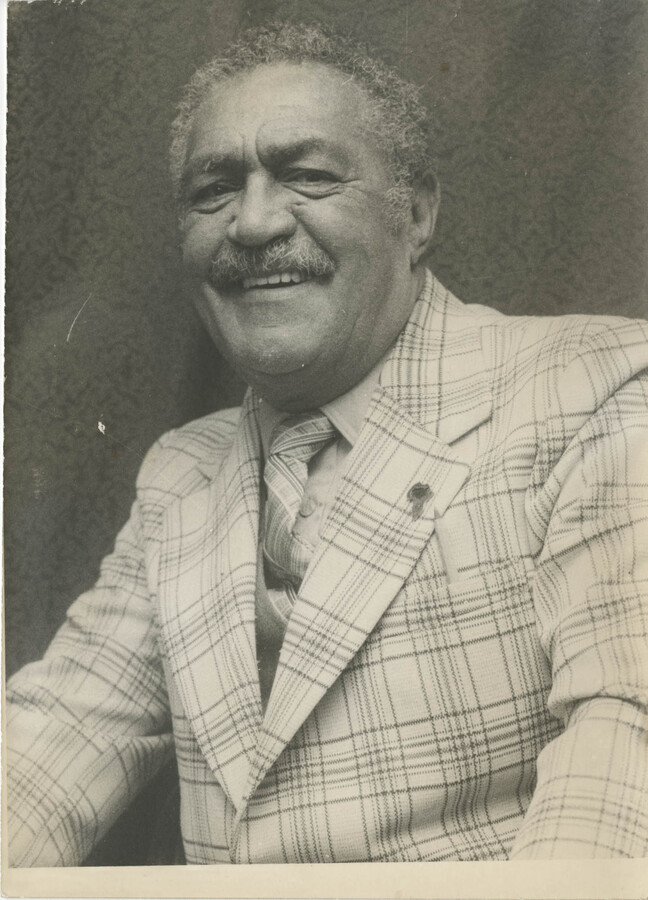

In 1955, in the midst of the modern phase of the civil rights movement, J. Arthur Brown became president of the local chapter and continued to carry the initiative of civil rights forward by leading class action lawsuits to desegregate public accommodations, initiating civil demonstrations against discriminatory employment practices, and collaborating with other civil rights leaders on a nation-wide scale.

In 1962, the College of Charleston did not admit prospective student Gretta Middleton despite segregation in education having been declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court nearly a decade prior. In a letter addressed to Middleton, Dean and Director of Public Admissions for the college, E.E. Towell, explained that she had been denied entry to the school on the grounds that her high school—an all-Black, privately funded Catholic academy—was “not accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools” and consequently she was “not eligible for admission to this College.” This, of course, was just one ruse of many that institutions of higher learning across the South used to continue to keep schools segregated well past the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision in 1954.

In fact, it wasn’t until thirteen years after the Brown decision that the College of Charleston admitted its first Black students: the first Black man to graduate was Eddie Ganaway in 1971 and the first Black woman to graduate was Linda Dingle Gadson in 1972. The integration of the College of Charleston would have been impossible without the indefatigable efforts of the local chapter of the NAACP.

The travails of Gretta Middleton and other unsung heroes like her remind us about how systems of oppression like that of Jim Crow segregation in the South often resort to circuitous legal subterfuge as a manner of dismissing dissent. By enforcing conventions, rules, and laws that at first glance are not explicitly racially motivated but nevertheless surreptitiously serve such purposes in order to bring about the same unfortunate outcomes, the perpetrators of these systemic acts of violence have shrouded themselves in an aura of plausible deniability in an attempt to preemptively exculpate themselves for their racist actions. In exposing how people continue to use this duplicitous veneer to arrest any progress towards racial justice, we can begin to identify and deconstruct other hidden modern-day iterations of oppression. As illustrated by this one example of activism by the NAACP over half a century ago, it isn’t easy: it’s tireless, often thankless work, filled with setbacks and false starts; but, if we are truly committed to creating a truly just and equal society, we will follow the guiding example of those—like Gretta Middleton, Eddie Ganaway, and Linda Dingle Gadson—who came before us.

Images