Thomas E. Miller House, 156 Smith Street

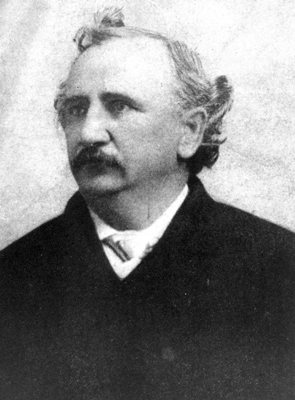

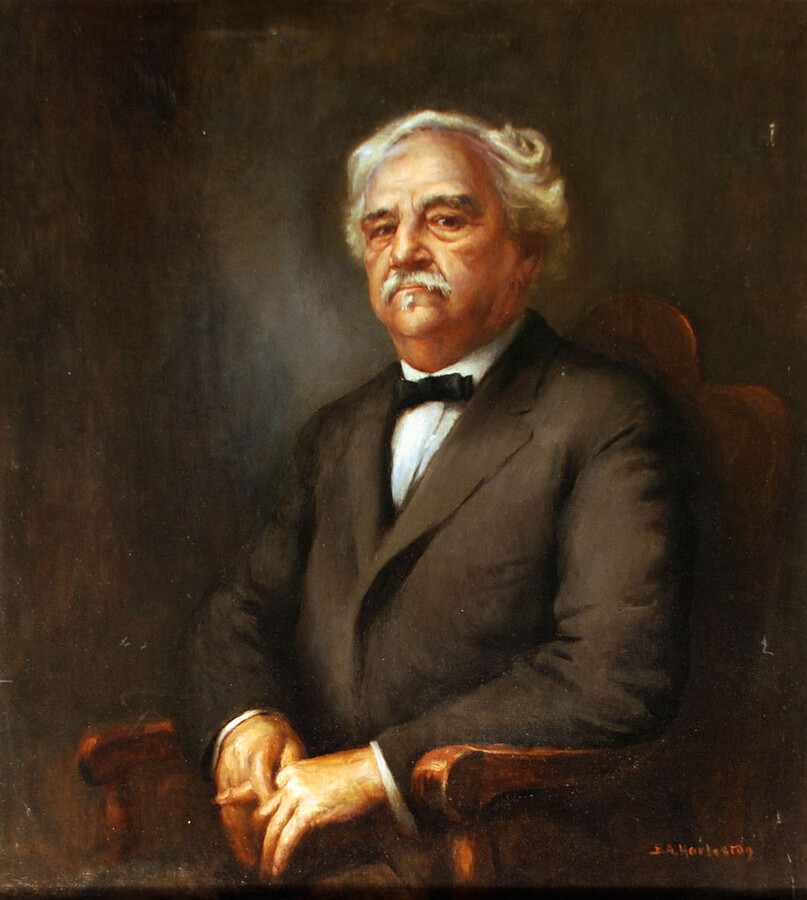

Thomas Miller was born on June 17, 1849 to free Black parents in Ferrebeeville, South Carolina. His family moved to Charleston in 1852 where he went to Black schools before moving to Hudson, New York.

Thomas Miller was born on June 17, 1849 to free Black parents in Ferrebeeville, South Carolina. His family moved to Charleston in 1852 where he went to Black schools before moving to Hudson, New York. He attended Lincoln University (PA.) on scholarship and graduated in 1872, continuing on to get a law degree from the University of South Carolina. Between 1874 and 1880, Miller served South Carolina’s general assembly as a member of the state’s Republican Party. He acted on the state party’s executive committee between 1878 and 1880 and would later serve as the party’s chairman in 1884.

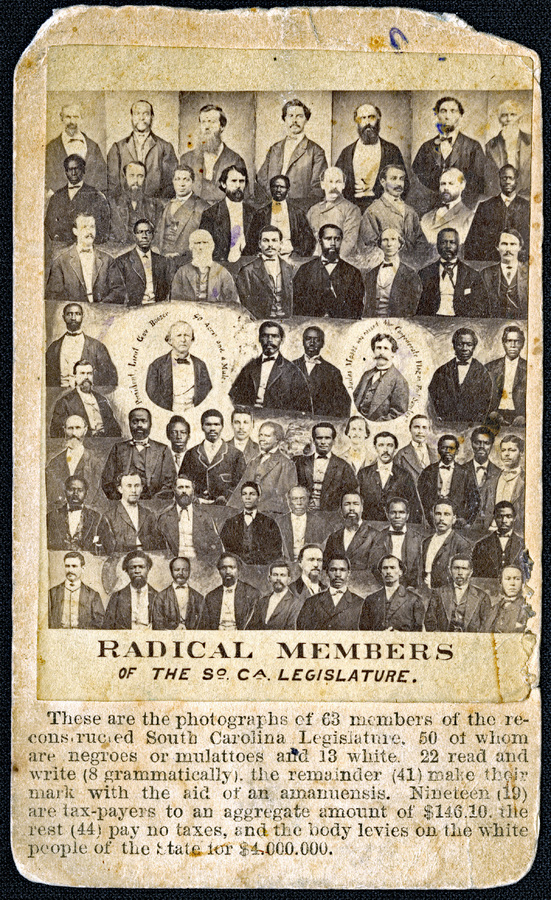

The tensions between Black Republicans and white Democrats during Reconstruction can be seen throughout Miller’s political career, especially in matters of election fraud. Thomas Miller ran against Democrat William Elliot in the race for Congressman for the Seventh District in 1888. The results showed that Elliot won, but Miller countered the results by arguing that most of the registered Black voters had not been allowed to vote. After reviewing the case, the House Committee on Elections announced Miller as the actual winner. He ran for re-election and faced off against Elliot again as well as the white Republican candidate, E.M. Brayton. The ballots for Miller were thrown out for minor discrepancies like the color of the paper or the wording on the ballot, and, because of this, Miller lost to Elliot. Miller protested the outcome, but the state Supreme Court ruled in favor of Elliot. The Democratic majority in the Congressional Committee on Elections also ruled that Elliot had won the election fairly when Miller brought the dispute to Congress’s attention. However, the Republican minority on the committee found that Miller should have actually won by over 3,000 votes.

In 1891, Miller spoke to the House of Representatives to support Representative Henry Cabot Lodge’s bill that let the federal government observe all federal elections and defend voters from any kind of violence or coercion directed towards them. He did this even at the expense of future re-elections into Congress, rejecting the Democrats’ claims that this was just a bill to let “incompetent and corrupt blacks” vote. Miller also went head-to-head with Georgia Senator Alfred H. Colquitt who propagated the lie that Blacks were the ones at fault for the South’s failure to recover from the recent economic downturn. Miller responded by saying that the whites in the South were the ones at fault by refusing Blacks their civil rights. He served as a state representative from 1894 to 1896.

Miller also was involved with the Constitutional Convention of 1895 of South Carolina that senator and former governor, Ben Tillman, organized to strip African American men of their right to vote. Miller, being a member of the delegation of nine Black lawyers and politicians during the Convention, protested against Tillman’s proposal to rewrite the state constitution that had been written during Reconstruction. Despite Miller’s efforts, as well as those of Representative Robert Smalls and Congressman George Washington Murray, the delegation was not able to prevent the implementation of the new constitution that made it harder for Black men to register to vote.

Miller later helped found the Colored Normal Industrial Agricultural and Mechanical College, in Orangeburg, South Carolina and served as its first president in 1896. While there, Miller advocated for the hiring of Black teachers for Black schools. The state governor, Coleman L. Blease forced Miller to resign in 1911 after Miller contested him in the 1910 election. In 1954, the institution was renamed South Carolina State University; and in 1965 it became one of the institutions of higher education that was designated Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).

After resigning from the College, Miller retired from politics and education, moving to Philadelphia in 1923. He returned to Charleston in 1934 and died there four years later. Miller’s descendants continued to live in the house at 156 Smith Street until 1950. The house was restored in 1987 and is still used as a residential home today.

Images