Marion Square and the “The 1869 Baseball Riot,” 329 Meeting Street

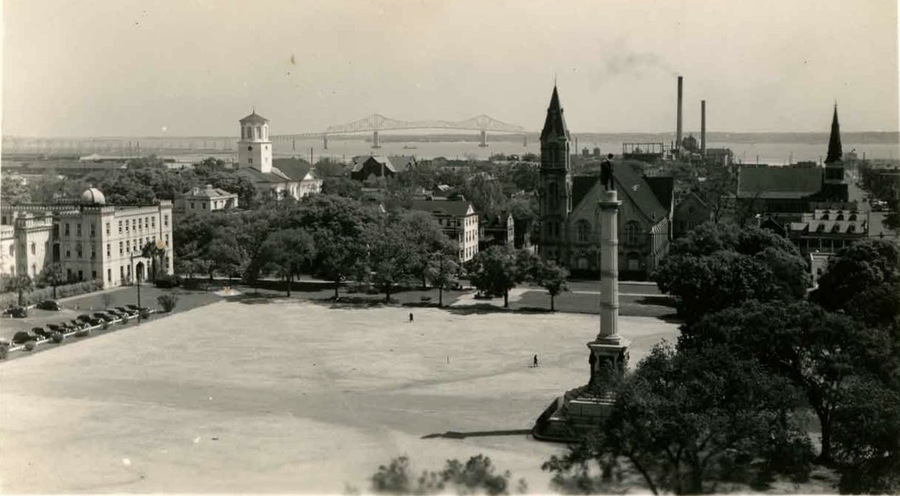

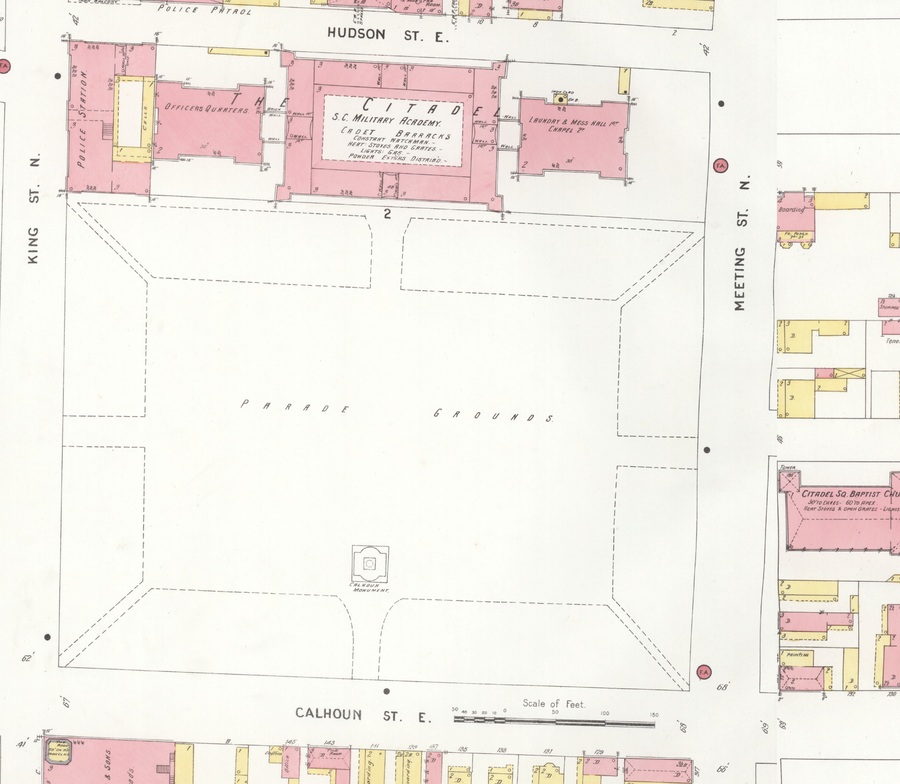

Marion Square is located in the heart of downtown Charleston. Named after Francis “Swamp Fox” Marion, the square is physically bounded by Calhoun, Meeting, Tobacco, and King Streets. The space today is what remains from a 10-acre parcel once owned by the Wragg family, given to the colony of South Carolina in 1758.

Marion Square is located in the heart of downtown Charleston. Named after Francis “Swamp Fox” Marion, the square is physically bounded by Calhoun, Meeting, Tobacco, and King Streets. The space today is what remains from a 10-acre parcel once owned by the Wragg family, given to the colony of South Carolina in 1758. In the 21st century, Marion Square serves as a central community gathering space, providing opportunities for recreation and relaxation while simultaneously serving as a space for social activism.

When Joseph Wragg died, his son John Wragg received 79 acres along King Street. In 1758, John Wragg sold 8.75 acres to the provincial government for £1,230 for use in the construction of a defensive wall to keep the city safe from Indigenous tribes and, later, the British. By 1783, on the assumption that there was no longer a need for defense, the 8.75 acres were transferred to the city government. In 1789, the state reacquired a portion of the land along the northern edge to build a tobacco inspection complex.

Marion Square is situated directly across from the historic Citadel Square Baptist Church and the South Carolina State Arsenal or the “Old Citadel.” The square is currently co-owned by the Washington Light Infantry and the Sumter Guards. Their objections prevented city officials from paving the park as a parking lot in the 1940s and also prevented its development as a shopping center. Currently, it is operated as a public park under a lease to the city of Charleston. Under the terms of the lease, the center of the square is kept open as a parade ground for the current Citadel cadets. Marion Square has also been a home plate for demonstrations in Charleston; examples range from recent protests of those demanding the removal of the John C. Calhoun statue, to vigils for victims of mass violence. It also was the site of significant historical events such as the largest riot in the city prior to the twentieth century.

On July 26, 1869, just four years after the end of the bloodiest conflict on American soil, Marion Square became the setting for a massive riot, which is referenced in newspapers as the “Base-ball Riots.” Two baseball teams from Savannah and Charleston played against each other and after the game the Washington Cornet Band - an all African American band - was asked to play “Dixie.” In the vicinity of the band, a large portion of spectators were formerly enslaved African Americans. They immediately started to yell at the band demanding that they not play that song--an aural reminder of the antebellum days of enslavement. A member of the freedmen threw a brick at the band and ordered them to cease playing. Local policemen and federal troops who were stationed at the Old Citadel, fixed their bayonets and charged the angry crowd in order to suppress any violence. The Washington Cornet Band and baseball teams were able to escape to their hotels, but still faced an angry group of African Americans who were still incensed at being subjected to hearing “Dixie.” The riot lasted well into the humid July night. Accounts suggest a fair amount of property damage and no loss of life.

Days after the riot, many African Americans who were under suspicion by white authorities were immediately jailed. The Charleston Baseball riot set the tone for how Freedmen would respond to overt actions of racism, which continued well into the 20th and 21st centuries. As of late, Marion Square has served as space of consciousness. Since the murders at Mother Emanuel A.M.E. in 2015, community members have demanded that the city of Charleston take action and remove the infamous John C. Calhoun statue. Calhoun was the vice president of the United States under Andrew Jackson and was also a state senator. He was a staunch supporter of slavery and described the insitutition as “a postive good.”

On the fifth anniversary of the Mother Emanuel A.M.E. murders, city mayor John Tecklenburg announced that the city council would vote to remove the statue and to place the statue inside a museum. Immediately after the announcement, some protested that placing the statue inside a museum was “not enough”. Protestors demanded that the statue not be considered for any potential display. Protestors soon climbed the statue to place signs on the statue, again demanding that their voices be heard. Soon after the statue became the target for eggs and vandalism. These protestors followed in the footsteps of Freedmen and women who vandalized the first version of the Calhoun statue after emancipation (the most recent version of the statue was redone in 1898 and raised over 100 feet to keep it safe from vandalism). This all followed the failed attempt in 2017 to add signage inorder to provide more “historical context” to the statue. But, opponents of the statue finally succeeded; on June 23, 2020, the Charleston City Council voted unanimously to remove the statue from its pedestal.

Marion Square will always live in duality. Whether it be the presence of statues of enslavers or freedmen celebrating their emancipation at the end of the Civil War in 1865, the landscape of Marion Square will always serve as an opportunity for new histories to be made.

Images