St. Peter’s Church, 34 Wentworth Street

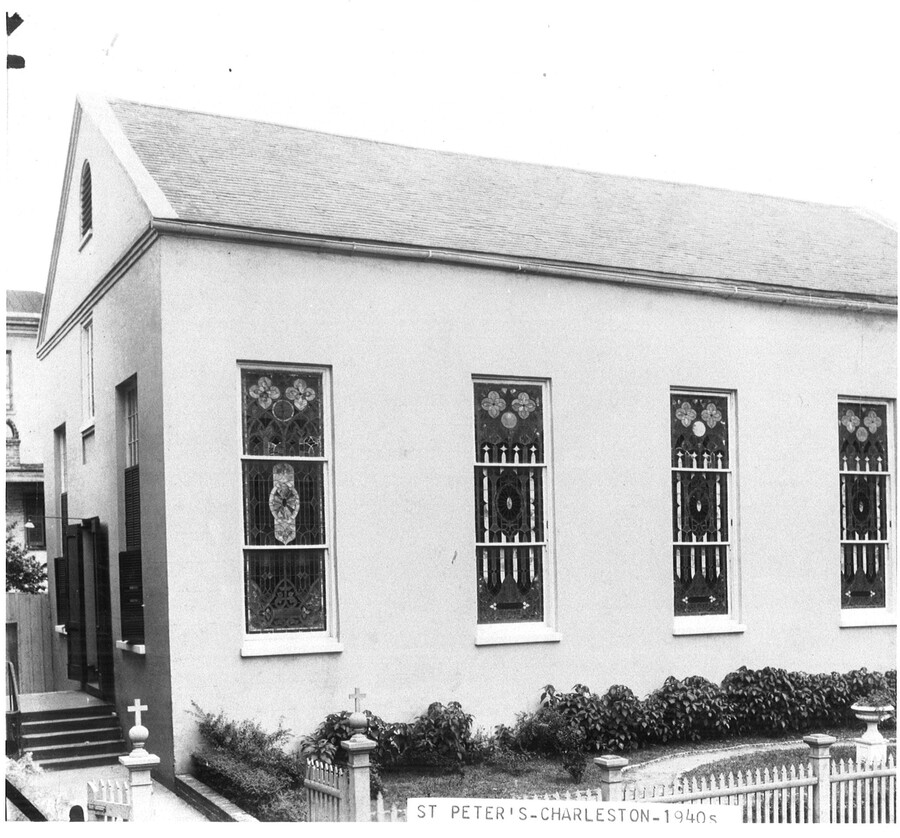

Here at 34 Wentworth Street stood St. Peter’s Catholic Church from 1867 to 1967. While a single church can be lost within the many steeples of Charleston’s “Holy City,” St. Peter’s Church illustrates an exciting chapter in Charleston history: Reconstruction.

Here at 34 Wentworth Street stood St. Peter’s Catholic Church from 1867 to 1967. While a single church can be lost within the many steeples of Charleston’s “Holy City,” St. Peter’s Church illustrates an exciting chapter in Charleston history: Reconstruction.

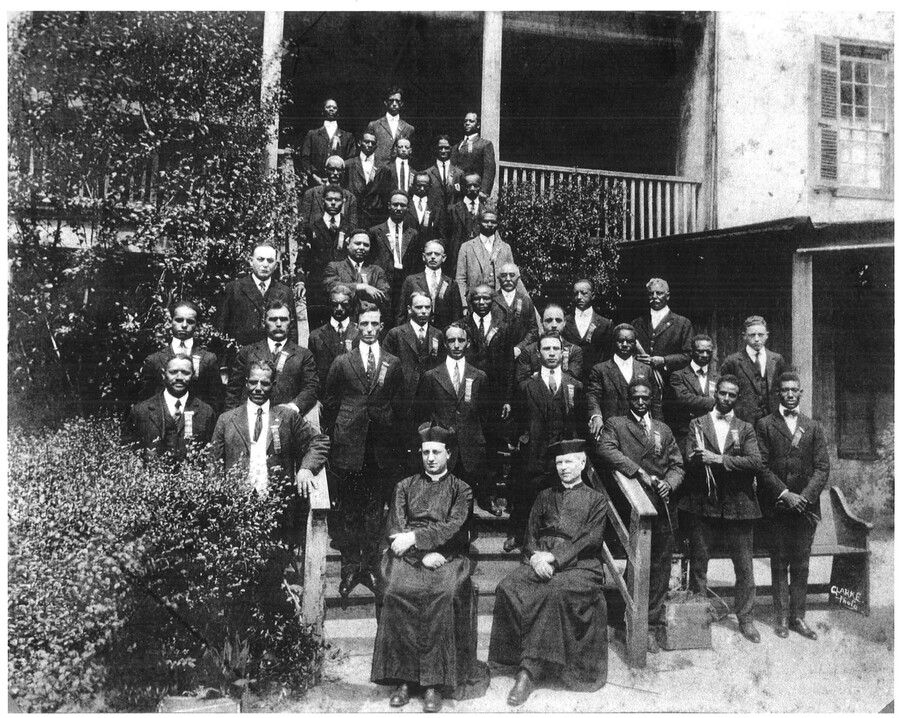

With the fall of the Confederacy, several institutions attempted to court the city’s newly freed population. Many times, the interested institutions were religious. Whether it was through pure goodwill or because of competition against rival churches, this era of religious expansion resulted in new schools, social networks, and communities among Black Charlestonians. One of these institutions was the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston.

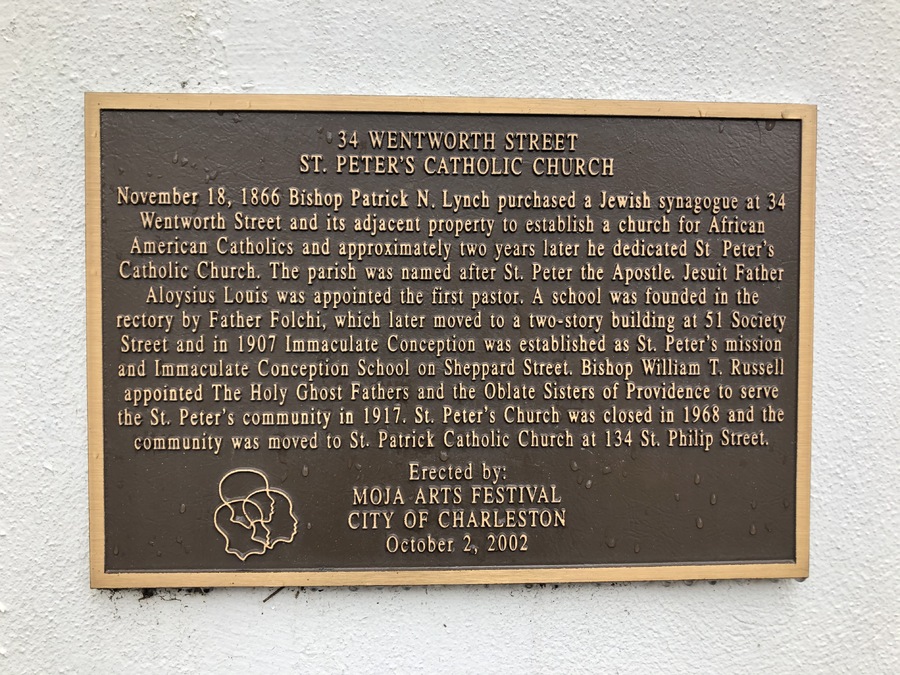

Although the Reconstruction era saw a new wave of attention towards African Americans in Charleston, the Diocese of Charleston had officially included African Americans since its creation in 1835. For years, Black Catholics, usually originating from French and Spanish colonies in Louisiana or the Caribbean, worshipped in the same space with their white Catholic neighbors, but were relegated to sitting in the galleries. The first separate church for Charleston's African American Catholics was St. Peter's, located at 34 Wentworth Street. Purchased by Bishop Patrick Lynch on January 12, 1867, the structure on the site was a former Jewish synagogue that was converted into the new St. Peter’s Church. Although Bishop Lynch first planned to act as the new parish priest himself, he instead appointed the Italian Jesuit priest Reverend Louis Folchi. One year later, Father Folchi and Bishop Lynch opened St. Peter's school in space formerly used as a dining room in the church.

While St. Peter’s saw initial growth under the leadership of Father Folchi, the church’s early success soon began to wane. In an 1869 letter to Lynch, Folchi stated that the decline in membership was due to the many Protestant churches that surrounded St. Peter’s. Folchi explained that Protestant congregations such as the Baptists and Methodists provided the raw energy that Roman Catholicism lacked. The Roman Catholic Church did not allow African American leadership in the church and discouraged the expression of emotions during mass, all aspects that Methodists and Baptist churches encouraged. The Catholic Church in the United States would not change this doctrine until the 1930s, with the integration of seminary schools and the Church’s first wave of African American priests.

Simultaneously, the Diocese of Charleston had difficulties keeping white Catholics out of St. Peter’s church. As in other Catholic Churches founded for Native Americans and African Americans, the parishioners at St. Peter’s did not have to pay a pew tax or rent. The Catholic Church’s goals were to increase conversion within the world’s disfranchised. While this strategy did attract some local African Americans, it also attracted the surrounding white Catholics who did not want to pay for a place in a pew. In many masses, whites outnumbered Blacks by four-to-one. This imbalance eventually led to even more African Americans leaving the Catholic Church due to the lack of space in churches explicitly made for them.

While the decline of St. Peter’s appeared outside the Catholic Church’s control, many within the Diocese saw Father Folchi as the problem. Several Charleston priests believed Folchi was deliberately sabotaging the mission he led. Reverend Claudian Northrop, the priest of St. Mary’s, one of the churches whites were fleeing, wrote to Bishop Lynch boldly claiming Folchi was intentionally luring whites from other churches to St. Peter’s. By doing so, Folchi was attempting to replace one group of Catholics with another group that he preferred. Reverend Claudian Northrop’s claim is supported by Folchi’s acknowledged racial prejudice. In letters to Lynch, Folchi openly voiced his disgust calling his parishioners and students “apathetic and indolent.” Instead of embracing African Americans’ cultural heritage, Folchi outright banned traditions such as dancing in church gatherings.

Eventually, Reverend Louis Folchi retired from St. Peter’s and left Charleston in 1875. He was replaced with Father Ward F. Cleary a member of the Josephite Fathers, who specialized in aiding African Americans. This pattern of cycling religious orders and priests would continue through St. Peter’s Church’s entire existence. This lack of steady guidance from a religious organization led to the parish’s failure. Father Phillip J. Haggerty was the last pastor appointed to St. Peter’s in 1961. The church closed in 1967, and the community moved to St. Patrick's.

In its place, St. Katherine’s Convent was established for the Oblate Sisters at the site of the old St. Peter’s. The Oblates would use this site for 31 years until they departed from South Carolina in 1999. Today, the site is home to the Drexel House, a home for young Catholic missionaries.

Images