Lincoln Theater, 601 King Street

The Lincoln Theater (601 King Street) was once an important center for community, culture, and entertainment for African Americans in the Charleston area.

The Lincoln Theater (601 King Street) was once an important center for community, culture, and entertainment for African Americans in the Charleston area. While the building that once housed the Lincoln Theater no longer exists, it is nevertheless crucial to remember the theater’s important role in providing a site with many meanings to African Americans during the Jim Crow era. The Lincoln Theater’s history is also interesting because it reveals an intertwined story of twentieth-century interactions between African American Charlestonians and Jewish European immigrants.

As early as the 1690s, the first Jewish European families made Charleston their home. They established residences and businesses in downtown Charleston and, by the 1880s, began to create a thriving Jewish social and economic corridor on King Street above Calhoun Street. Upper King Street was commonly referred to as “Little Jerusalem” and was home to a variety of families and businesses, including doctors’ offices, delis, kosher meat markets, religious centers, and retail shops.

Beginning in the late 1870s, Jim Crow legislation enforced segregation in public places such as stores, schools, libraries, and entertainment centers. In Charleston, this segregation also led to the creation of majority African American neighborhoods and communities in areas surrounding Upper King’s “Little Jerusalem.” Some Jewish business owners took advantage of their proximity to African American neighborhoods and created a space for African American clientele—a decision considered radical in Jim Crow Charleston.

In the late 1910s, local residents approached Samuel Banov who owned a storefront and residence near the corner of King and Spring Streets. They convinced Banov to purchase the adjacent property, 601 King Street, and convert the building into a theater for African Americans. Banov immediately made preparations for the opening of the Lincoln Theater, hoping to attract African American investors and shareholders by advertising in the News & Courier, “Let the Lincoln Theater be for the Colored People and by the Colored People.”

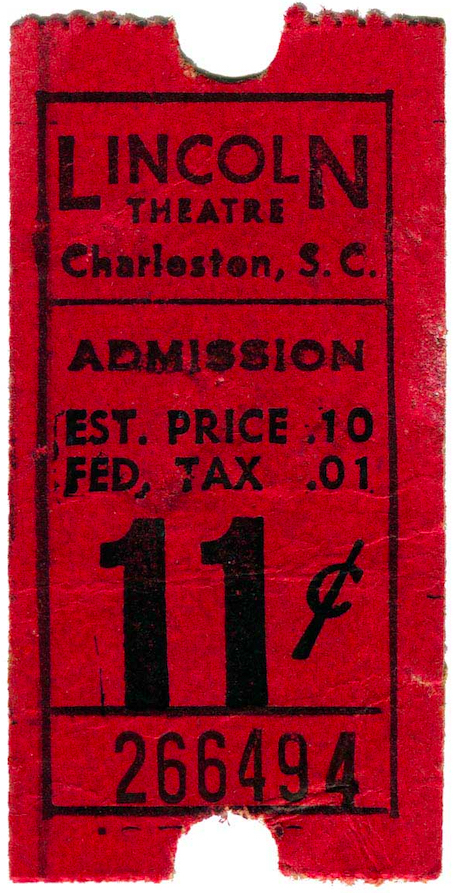

After a period of remodeling, the Lincoln Theater opened in November of 1919, joining over thirty other theaters in downtown Charleston. Of those theaters, only one other catered exclusively to African Americans—the Dixieland Theater. The Lincoln Theater joined this short list of theaters for African American patrons but outlasted Dixieland, which closed in 1923. From 1923 to 1972, the Lincoln was the only theater that catered solely to African Americans in Charleston.

Although the property was owned by Banov, the Baijou Amusement Company—an African American theater chain based out of Nashville, Tennessee—managed the Lincoln Theater. The Baijou Amusement Company appointed Damon Ireland Thomas as head manager of the Lincoln Theater in 1922. Thomas was born in 1871 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Before managing the Lincoln Theater, Thomas successfully managed theaters along the East coast. In addition to managing theaters, Lincoln also wrote a weekly column in the Chicago Defender advocating support for Black films and theaters.

Under Thomas’s leadership, the Lincoln Theater prospered not only as a site of entertainment for African Americans in a strictly segregated Charleston, but also as a center of community. The majority of entertainment offerings at the Lincoln Theater included vaudeville shows and films but Thomas offered community lectures, too. Thomas also scheduled live music, hiring African American singers, bands, and performers. The Lincoln Theater offered entertainment and community for many patrons and economic opportunity for others—a number of local African Americans found employment and entertainment at the theater.

In addition to contributing to the Lincoln Theater’s importance as a center for Black culture, entertainment, and community, Thomas went one step further in supporting African Americans in Charleston. Thomas shared his economic success through philanthropic activities. For example, in 1942, Thomas donated land to build an African American fire house in a segregated neighborhood near the theater. Station 15 still stands today at 162 Coming Street.

Thomas continued to manage the Lincoln Theater until his death in 1955. Less than a decade after his death, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was enacted, outlawing discrimination and segregation of public spaces. In southern cities like Charleston—a city built upon white supremacy—elite whites vehemently resisted integration; the Lincoln Theater remained open throughout this period. In Charleston, local high school students, faculty, workers, and local activists led civil rights movements throughout the 1960s with demonstrations like the Kress sit-in (1960). By the 1970s, Charleston was considered desegregated. The Lincoln Theater lost relevancy and popularity after Thomas’s death and the Civil Rights Act, ultimately closing in 1972.

After sitting abandoned for nearly a decade, tentative plans to turn the theater into affordable housing for the elderly circulated in the early 1980s. Unfortunately, these plans were halted by Hurricane Hugo, which significantly damaged the Lincoln beyond repair. The building was demolished in 1989. Although the Lincoln Theater no longer stands today, its history represents African American solidarity, community, and strength in the face of Jim Crow segregation and hostility

Images