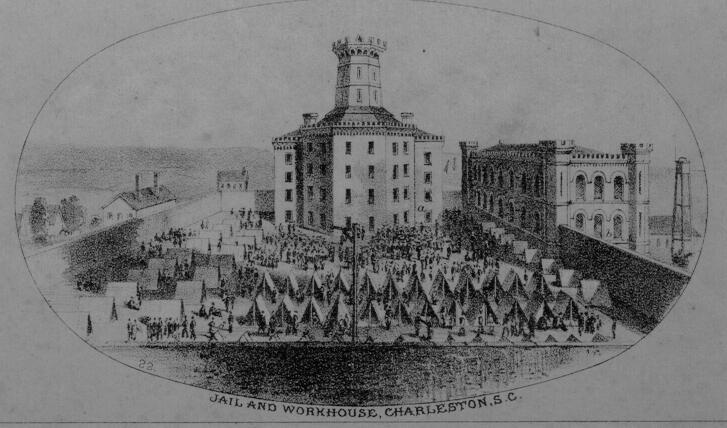

Charleston Work House and "Sugar House"

(CONTENT CONTAINS GRAPHIC DESCRIPTIONS OF TORTURE)

“I have heard a great deal said about hell, and wicked places, but I don't think there is any worse hell than that sugar house.”

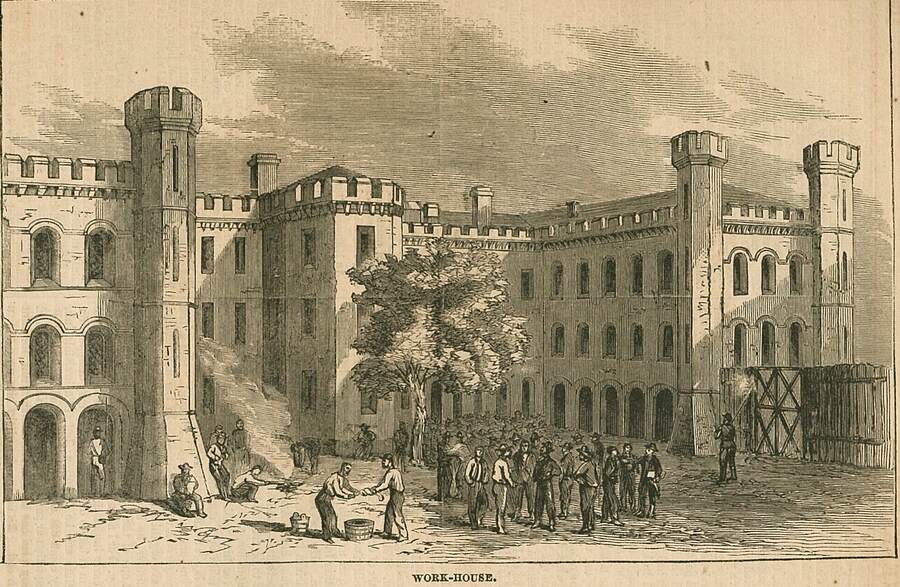

Before South Carolina became famous for its prized Carolina Gold rice, there were several agricultural experiments conducted to determine what would be the most lucrative crop to cultivate here in the Lowcountry; among the various citrus fruits, indigo, and even silkworms, there was sugar. As the coastal region of South Carolina owed its earliest colonists to immigration from Barbados and other English-occupied Caribbean islands that specialized in sugar production, many early colonists were hopeful that this region would prove to be equally acclimated to such a lucrative cash crop as well. When the city’s main workhouse, located at the intersection of Magazine and Mayzck (now, Logan) Streets, burned to the ground in 1780, the prisoners were temporarily housed in the defunct building on Broad Street that had formerly been the site for storing sugar until a new structure could be rebuilt. Once the structure had been rebuilt by the early nineteenth century, the conflation between the “sugar house” and the “workhouse” had become permanent.

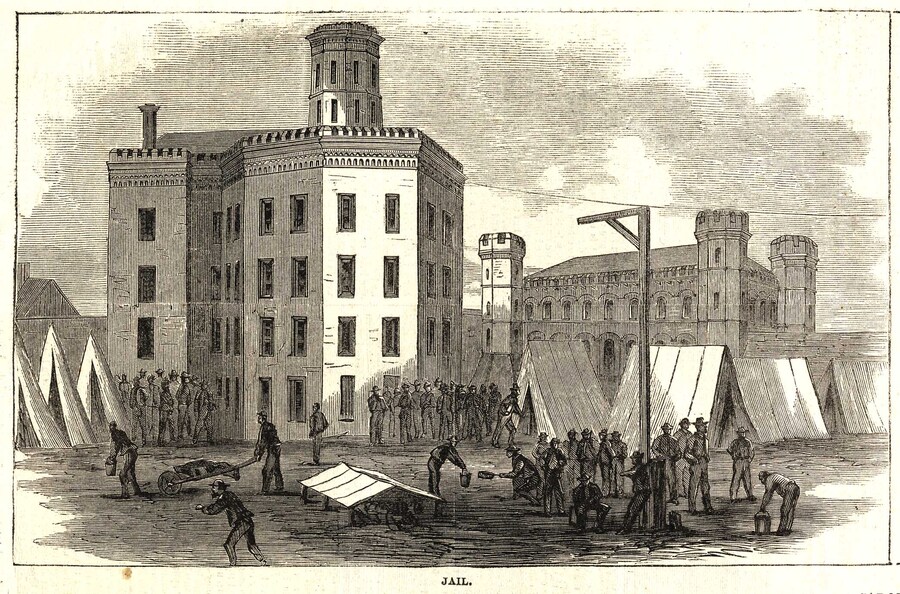

After several conspiracies of a slave revolt—most notably the plot Denmark Vesey led in 1822—the workhouse became a site for the nearly exclusive corporal punishment of enslaved people. It was located directly adjacent to the city jail. If enslaved people were thought to have overstepped their boundaries, they would be brought here (as the wry euphemistic phrase went) “for a bit of sugar.” Enslavers who did not want to sully their own hands by disciplining their slaves would pay a fee in order to have someone else commit this cruel act for them in their stead.

The methods of punishment took many forms. Stockades were a simple but brutal form of torture. Prisoners’ legs would be forced through a wooden plank, their hands would be tied by rope, and their necks would be fastened by a heavy chain to one of the beams in the damp, unlit cellar underneath the main floor of the building. Although he himself never was confined to the workhouse, William Pinckney, a former enslaved person, confirmed that, after having been confined for weeks at a time and deprived of any basic necessities, “sometimes the slaves died in [the] stocks.”

In between confinement to the stockades, whippings were especially common, and were typically employed by the use of a paddle, a whip, or even a cat o’ nine tails. One particularly gruesome implement was known as the bluejay, and whenever it was applied it would puncture holes into the flesh. In “Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave,” a serialized account published by the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, one former slave, named James Matthews, recounts his horrifying experiences in the workhouse. After having escaped from his owner, Mordecai Cohen, Matthews was captured and taken to the workhouse for his punishment, where he was whipped upwards of two hundred times over the course of a two-week period. After suffering such brutal treatment, Matthews recalled that his back “would be full of scabs, and they whipped them off till I bled so that my clothes were all wet. Many a night I have laid up there in the Sugar House and scratched [the scabs] off by the handful.”

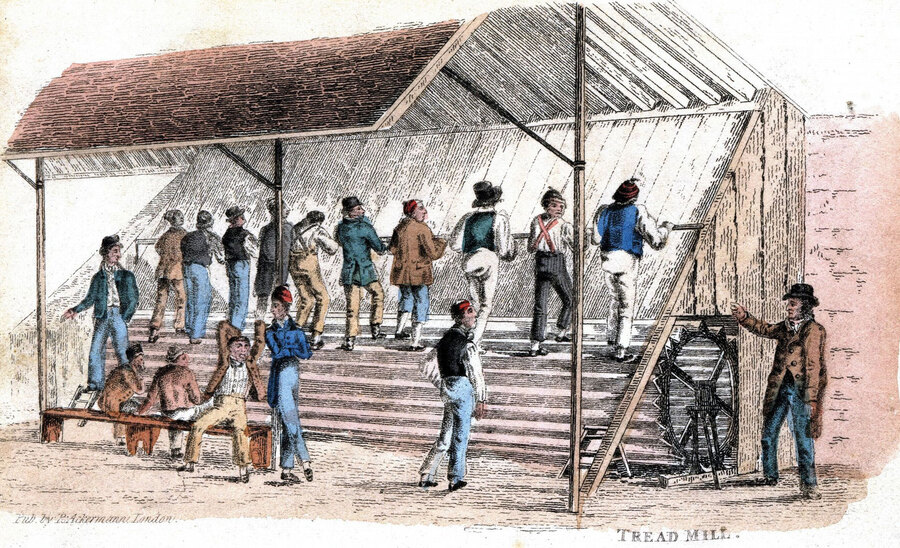

Another form of torture employed in the workhouse was the treadmill. With its origins in humanitarian prison reform of the early nineteenth century, the treadmill was a device that sought to instill the proper work ethic within the inmate, supposedly to bring about their moral rehabilitation. The treadmill consisted of a cylinder that had a series of steps that the prisoner would step onto in order to keep the machine turning in order to grind corn down for further processing. Each step required one to exert a considerable amount of pressure in order to keep the cylinder rolling. After having been “stripped entirely naked,” enslaved people would be expected to do this for days on end wearing only “a small piece of cloth round the body, and a cap was drawn over their face.” Those who were considered to be too sluggish would have the backs of their legs beaten or whipped and with each step the enslaved person ran the risk of falling and breaking a limb.

Another form of punishment practiced at the workhouse as well as elsewhere throughout Charleston were public punishments, such as whippings. Public punishments such as these were intended to reinforce the social mores of the time period. It should be noted that both races and sexes endured public whippings well into the antebellum period; however, as the decades wore on many aristocratic whites grew concerned that this practice—meted out to Blacks as well as to whites—effectively undermined white supremacy, as a “crowd of our colored population” that congregated to view such a display could secretly relish in the “degradation of the white by the same punishment” that their own race bore. Consequently, all whippings of white criminals would be held behind closed doors (such as within the confines of the city jail) while the whipping of Blacks would continue to be exposed openly for all to see.

In our day and age, we should note that we are continuing to grapple with a discriminatory criminal justice system that metes out longer and harsher sentences to racial minorities than to white people—similar to how punishments given to enslaved people in the workhouse differed greatly from those to white criminals in the adjacent city jail. The workhouse continued to be used as a house of corporal punishment after emancipation, until the building was razed after the disastrous earthquake of 1886. Tucked away out of sight and out of mind from the hustle and bustle of downtown Charleston, the suffering wrought at this site so many years ago proves to be an all-too-eerie analog to the fact that the pain and suffering of Black and Brown people in our twenty-first century criminal justice system remains equally absent from our attention today.

Images