Post & Courier Office, 134 Columbus Street

As the longest continually publishing newspaper in the South, the Post and Courier has offered well-respected journalism both within and outside of the Lowcountry for centuries, and continues to do so to this very day.

As the longest continually publishing newspaper in the South, the Post and Courier has offered well-respected journalism both within and outside of the Lowcountry for centuries, and continues to do so to this very day. Throughout much of the twentieth century, however, it was formerly known as the News and Courier prior to its merger with the Evening Post in the early 1990s. Many of its past and present editors have offered commentary on contentious social issues affecting not only the nation, but also local issues that directly relate to Charleston.

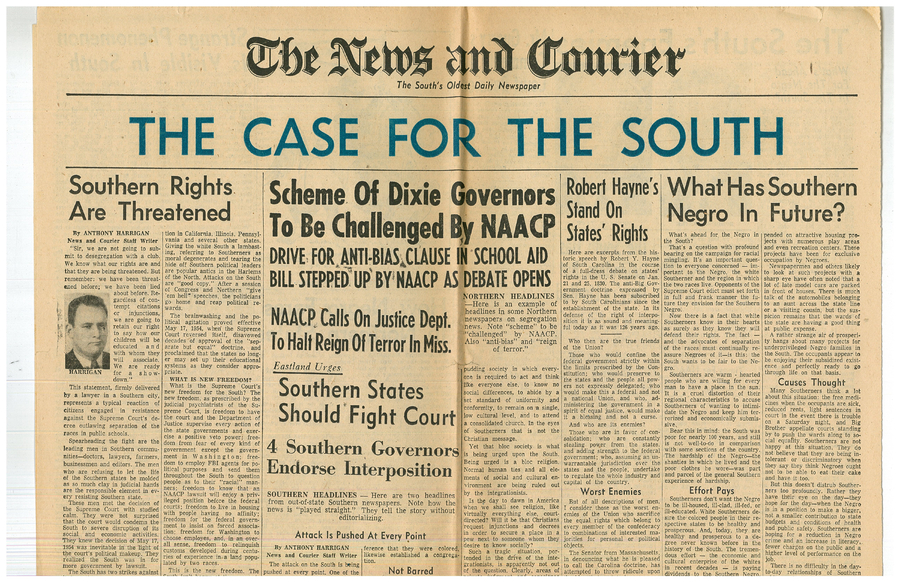

One such editor was Thomas R. Waring, Jr., a native of the Palmetto City and incidentally the nephew of prominent civil rights advocate Judge J. Waties Waring. While J. Waties Waring was a fierce advocate of desegregation, Tom Waring himself was an equally fierce advocate for segregation. Using his public platform as a well-respected journalist at the News and Courier, Tom Waring loudly trumpeted some of the most hateful and vulgar denunciations of the civil rights movement, and, in doing so, exposed another dimension of the throughline between slavery and segregation.

As the mouthpiece of rabidly unapologetic racism and with its wide readership, the News and Courier was a painful object of criticism to the civil rights advocates in Charleston. This was largely the reason why activists selected it as the symbolic endpoint of a public march to protest prejudice and injustice in July 1963. But, as the demonstrators proceeded onto Columbus Street towards the building late in the evening, the City strategically positioned police officers in front of the building. The officers began harassing the protestors and hauling them away in their patrol cars when, during what had up until this time been a peaceful demonstration, a brick flew from the crowd of aggrieved citizens and struck one of the policemen.

Pandemonium ensued. Fighting broke out between the protestors and the police, and, in an intimidating show of force, the fire department arrived with two of its vehicles and made it apparent that it would be more than willing to use its high-pressure hoses on the demonstrators—similar to what happened in Birmingham, Alabama earlier that year. Shortly thereafter the mayhem subsided. Sixty-eight people—mostly African Americans—were arrested that night. This was not the first confrontation between civil rights advocates and those who sought to enforce the status-quo in the city, nor would it be the last.

Upon further reflection, one notices that a striking parallel between the antebellum period and the post-war era, in that segregationists--not unlike slaveholders--argued that intimidation and violence were necessary measures in order to keep African Americans in a subservient position. Whereas during slavery the most common mode of punishment was the bullwhip, Waring threatened that “[i]f it were necessary to use machine guns, I’d use them.”

Paranoia reflective of the many rumored slave revolts is also echoed in the notion that the civil rights movement was somehow a conspiracy orchestrated by Communist agitators in an attempt to instigate domestic unrest in the United States. Even the fear of interracial sex, pejoratively referred to as “race mongrelization,” is invoked throughout many of Waring’s editorials. Sexual relationships between Black men and white women were also, as perceived by slaveholders, arguably the most insidious threat posed by the abolition of slavery. While many segregationists couched their opposition to the civil rights movement in the more “respectable” rhetoric of states’ rights, Waring shamelessly reveals that at its core such a supposedly principled position was in fact rooted in irrational, deep-seated fears that ultimately can be traced directly back to slavery.

While it is easy to dismiss an especially repugnant figure such as Tom Waring as an idiosyncratic individual whose ideas were not reflective of society as a whole, such excuses ignore the strong segregationist stances of many white people at the time, and the fact the paper enjoyed a large white readership. In fact, there were other journalists who contributed to such sentiments, most notably James J. Kilpatrick of The Richmond News Leader, who was one of the most influential figures in formulating the response of Massive Resistance in opposition to the Civil Rights movement, and whose columns were carried in the News and Courier. In this respect, while Waring may indeed have been only one person, he, along with a coterie of other like-minded journalists, fundamentally shaped others’—especially white Southerners’—attitudes and reactions to the Civil Rights movement. With this in mind, we would do well to ask ourselves how contemporary news coverage affects, and indeed sometimes distorts, our perception of the on-going civil rights movement today.

Images