Inheritance: Septima Poinsette Clark's Family, 1850s-1910s

Septima Poinsette was raised by parents who worked tirelessly to make sure their children were educated and successful, despite the obstacles facing Black citizens throughout their lifetimes.

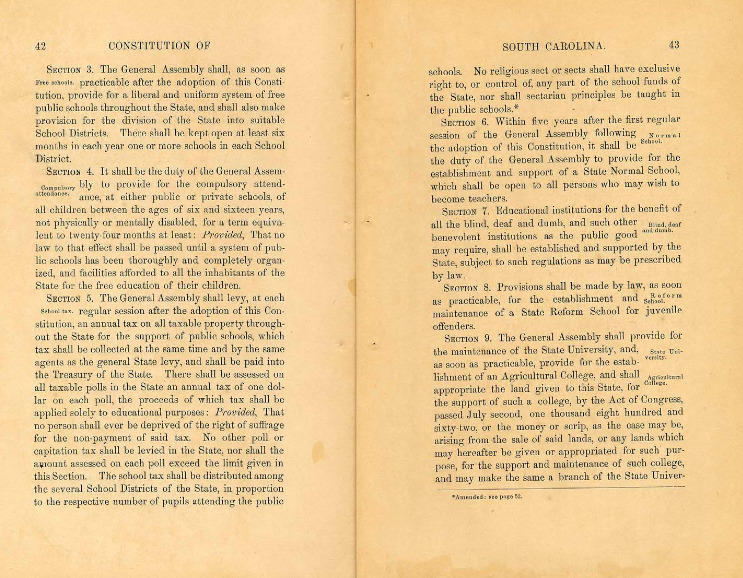

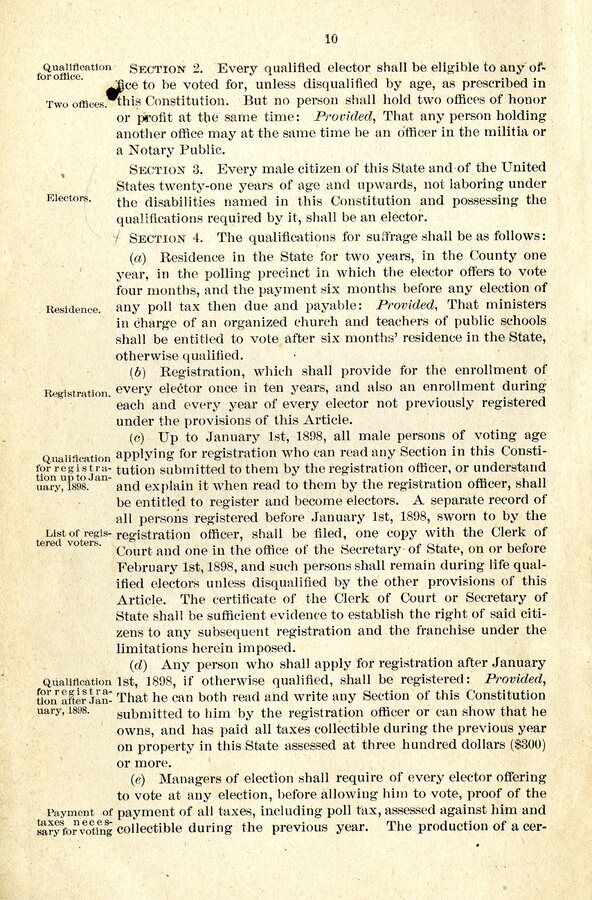

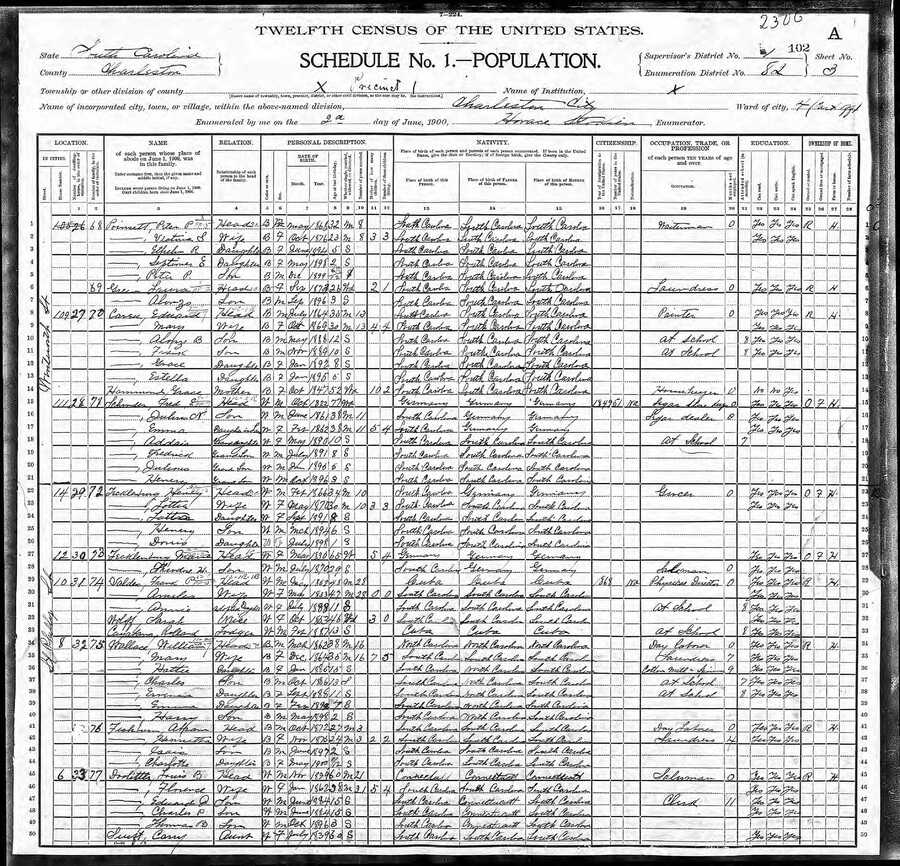

When Septima Poinsette was born in a house on 105 Wentworth Street in 1898, Black citizens had few legal rights and little opportunity to advance in American society. Virtually no Black people could vote; although Black men in South Carolina gained that right during Reconstruction (1865-1877), white South Carolinians rolled back Blacks’ civil rights in the late 1800s. Reconstruction had extended voting rights to all men and had implemented a free public school system, but South Carolina’s 1895 constitution excluded Blacks from voting and mandated segregated schools. Amid these repressive circumstances, Peter and Victoria Poinsette managed to create full lives for themselves and their children. They succeeded, not only through their personal efforts, but also with the support of Black schools, churches, clubs, and neighborhoods that surrounded the Poinsette family in Charleston.

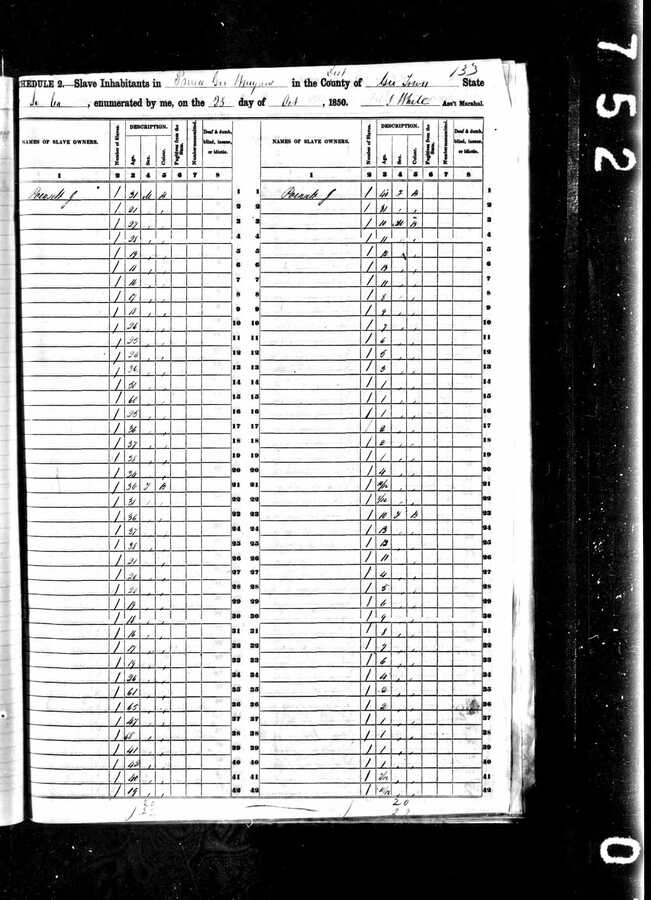

Records do not indicate how long Septima Poinsette Clark’s ancestors lived in the Americas. She believed her mother’s family had some Native American ancestry, which she and her cousin remembered as Seminole, Muskhogan, or Santee. As with many Black and Indigenous people, “official” records are not available to confirm all these family memories. Regarding her father, Ms. Clark told interviewers that his enslaved mother died while he was young, and that she knew nothing about her paternal grandfather. Her father, Peter Porcher Poinsette, was probably born in the late 1840s near Georgetown, SC. His enslavers were Mary Izard Pringle Poinsett and her second husband, Joel Poinsett, a diplomat, politician, and trustee of the College of Charleston.

As an enslaved child, Peter Poinsette had received no schooling. Like most Black South Carolinians (and over forty percent of whites), he was illiterate. His wife, Victoria Anderson Poinsette, was better educated. She was born in 1870 in Charleston, then spent part of her girlhood in Haiti, where she received some education. “That made her the proud soul she was all her life,” her daughter later said. As an adult, Mrs. Poinsette, who worked from home as a laundress, was active in Black women’s clubs and in her church, Old Bethel United Methodist, near the College of Charleston on Calhoun Street. (Old Bethel, a Black congregation, had originally worshipped with whites in this building, until the white members of Bethel United Methodist gave them the building and moved to a new church across the street.) Mr. Poinsette worked as a waiter, caterer, and custodian, and briefly co-owned a restaurant on State Street; he was a member of Centenary United Methodist Church. The Poinsette children attended both churches as well as Sunday school and services at Zion Presbyterian and Emanuel AME Church.

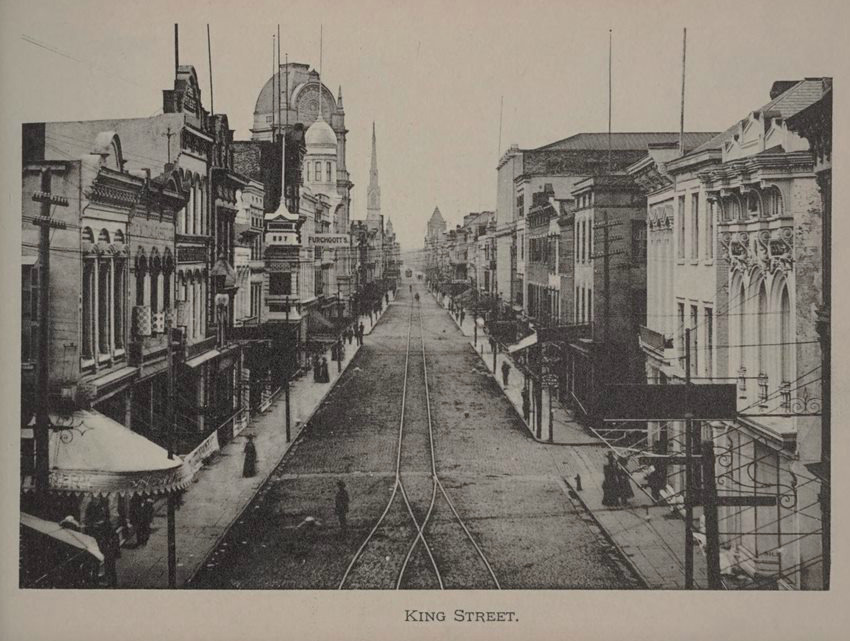

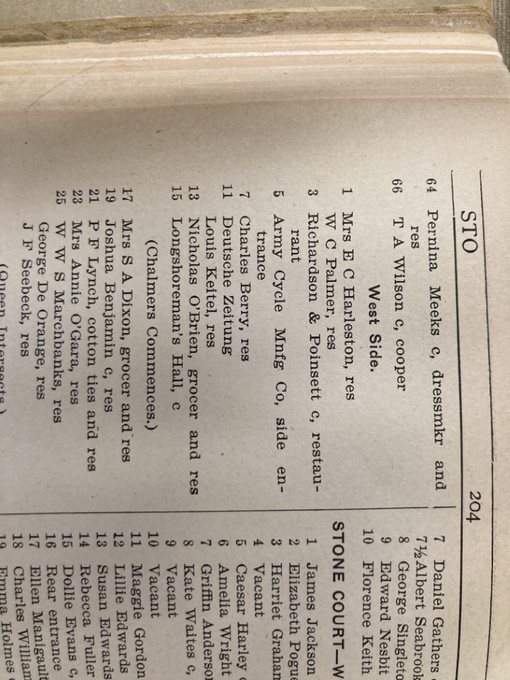

When Septima Poinsette was six, her family moved to a house on Henrietta Street. There the children helped their mother wash and iron her customers’ laundry, fetched buckets of water from the fountain in Marion Square, and on some Sundays, took walks with their mother down King Street and along the Battery. At home, Mrs. Poinsette enforced strict discipline, and she stood her ground with other people. Once when a policeman came through the yard, saying he was pursuing a suspect, Mrs. Poinsette shooed him away, saying, “I’m a little piece of leather, but I’m well put together, so don’t you come in here.” Mr. Poinsette had a more tranquil disposition. He often cooked for the family, and his daughter later recalled “sitting around that pot-bellied stove” and absorbing three important lessons from her father: always tell the truth, never “exalt yourself,” and “see others as Christ saw them. . . seeing that there is something fine and noble in everybody.”

Decades later, Ms. Clark reflected on her parents’ influence. “I always say that I stand on the platform that was built by both my mother and my father. My mother with her courageous philosophy, and my father with his non-violent philosophy. I think I have some of both in me.”

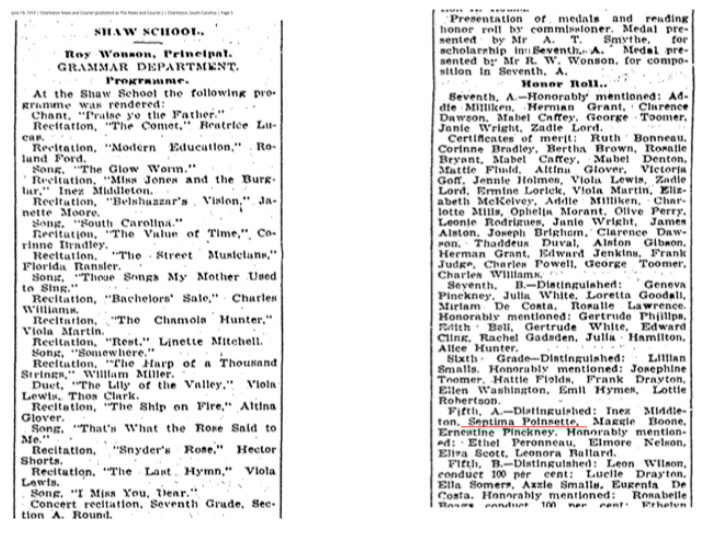

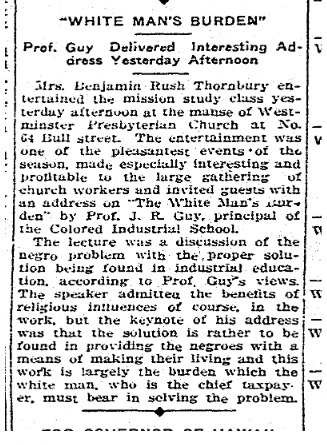

Both parents wanted the best possible education for their children. Mrs. Poinsette supervised the children’s homework and arranged for music lessons and, in some years, for private schooling. “There were lots of Black women who had little schools in their homes,” Ms. Clark later recalled, “and I really learned in that kind of school.” In other years, she attended segregated public schools, including Charleston Colored Industrial School (now Burke High School), which then ended at the 8th grade. There were no public high schools for Black students.

In 1912, eager to continue her education, the teenaged Septima Poinsette enrolled in the Avery Normal Institute, a private school founded in 1865 to train Black teachers. Encouraged by her family, neighbors, and Black educators in Charleston, she was on her way to achieving more than her parents had been allowed to do.

Images