Education: Septima Poinsette Finds Her Calling, 1912-1919

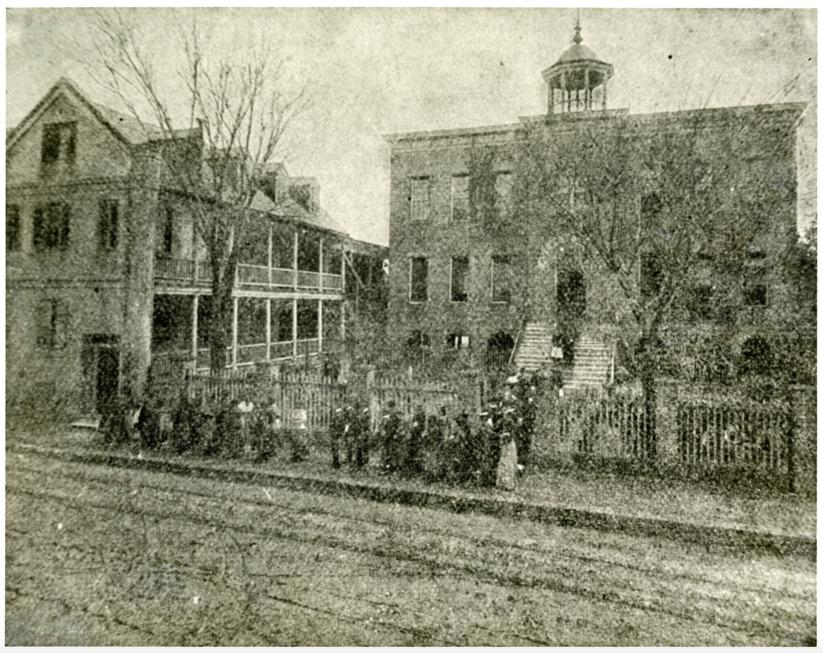

At the Avery Normal Institute at 125 Bull Street (now called the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture), Ms. Septima Poinsette studied, taught, and began participating in activism.

Septima Poinsette entered Avery Normal Institute as a high school freshman in 1912. Six years later, in 1918-19, she was teaching here, helping support her family, and becoming politically active. Her parents were successfully raising their large family, although their opportunities were limited by South Carolina’s racist laws and the Poinsettes’ working-class status. Septima Poinsette was restricted by these circumstances as well, but during her years at Avery, she broadened her intellectual horizons, boosted her earning power, and strengthened her desire to improve the lives of others.

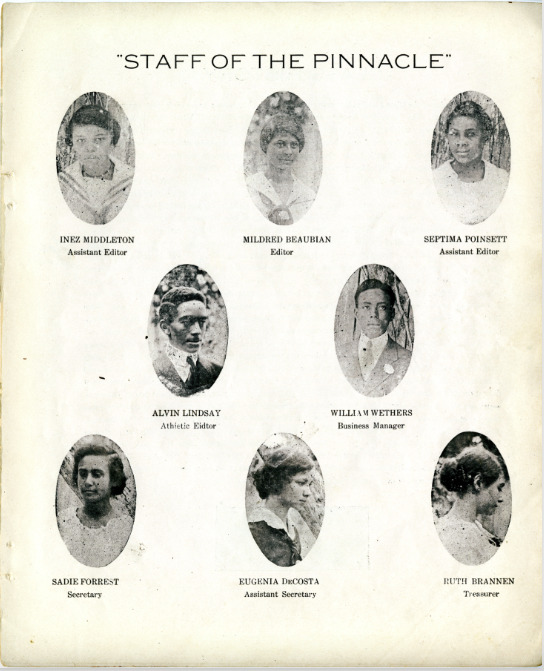

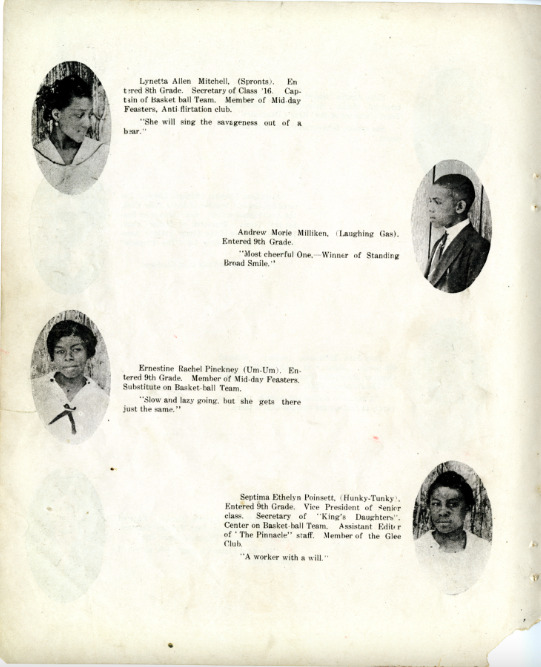

Avery was founded just after the Civil War to train Black students to teach. Septima Poinsette had wanted to be a teacher since grade school, when children in the neighborhood called her “Little Ma.” At Avery, she thrived under nurturing teachers and a rigorous liberal arts curriculum that included science, literature, history and government, and foreign language. She found time for extracurricular activities--editing the yearbook and performing in plays--while also fundraising for her church. Before and after school, she babysat to earn her tuition.

As a private school, Avery’s student body included many students from Black families that had been free, well educated, and financially successful before the Civil War. Septima Poinsette felt she “was considered beneath a lot of the students there since my mother was a washerwoman and my father had been a slave.” Avery’s leaders, however, sought to create a more equitable atmosphere—for example, requiring students to spend no more than one dollar on the material and trimming for their prom dresses. Clark later recalled how much she appreciated the way the Avery teachers “came to your home, regardless of what kind of a house you had, and talked with your parents. And they wanted me to go to Fisk [University] when I finished.” Her parents wanted this for her, too, but she knew they couldn’t afford Fisk’s tuition, so when she graduated at age eighteen, she went to work, helping to support her family.

Laws prohibited Black teachers from teaching in public schools in the city of Charleston. Septima Poinsette’s first job was at Promise Land School on Johns Island, hours away by a small motorboat. There she taught over 100 Black children and earned $35 per month. Nearby, a white teacher with three white students earned $85 per month. Clearly, South Carolina’s educational system was separate, but not at all equal. From this modest salary, the frugal Ms. Poinsette earned enough to pay her board with a Johns Island family and send her family twenty dollars a month. She even saved money to buy a bicycle for her brother and fabric for her sister Lorene to make “a dress that she could sling around in.”

Teaching and living on rural Johns Island was challenging. It was worlds away from Charleston. Many residents were farmers who worked for white landowners. Children were often required to work with their parents, only attending school a few weeks per year. Even so, “Miss Seppie,” as she was called, taught all students, whenever they could attend and whatever their grade level. She also organized a PTA, taught sewing classes, helped tend gardens, attended church services, and assisted neighbors who couldn’t read and write. Building these community relationships made her a more effective teacher and leader.

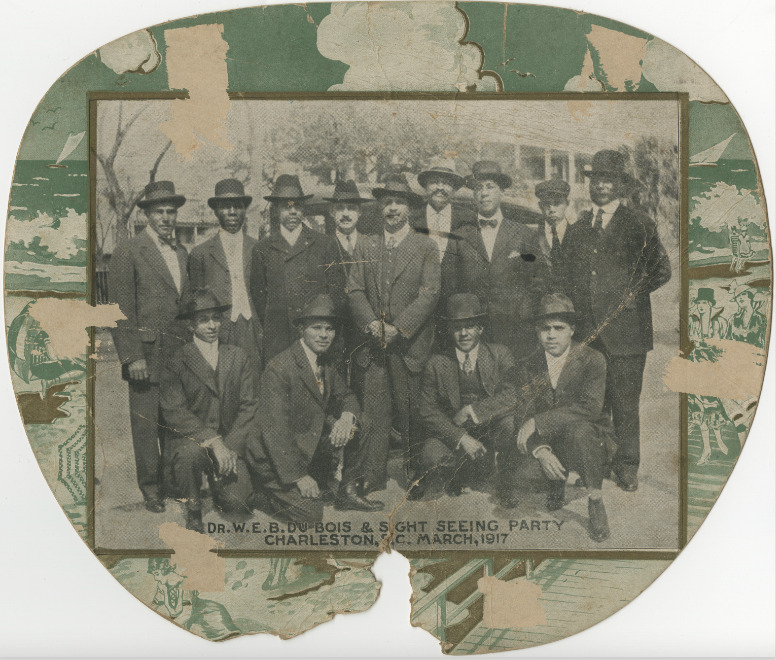

After two years at Promise Land School, Ms. Poinsette taught at Avery in 1918-19. She also joined the Charleston chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which had been formed in 1917; its president was Avery graduate Edwin “Teddy” Harleston. Publicly participating in NAACP activities required courage. Hostility to Black agency was on the rise. In many locations in the U. S. in 1919, white mobs attacked Black Americans, in a period known as “Red Summer.” In May 1919, a mob of whites attacked Black Charlestonians, killing two. The Poinsettes could hear the uproar from their porch.

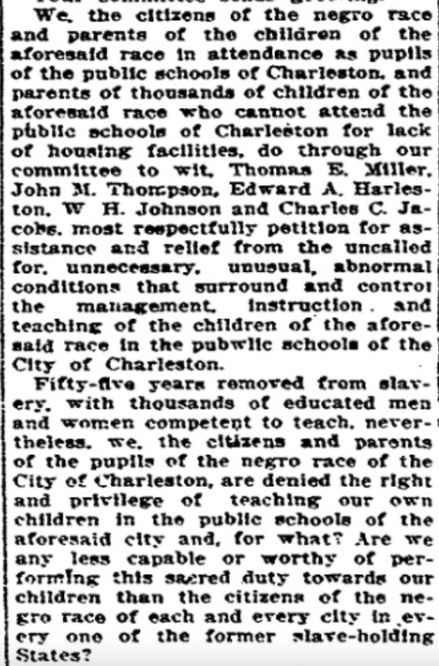

That same year, the Charleston NAACP had called for the city to hire Black teachers for students in its Black schools. Septima Poinsette supported this campaign, having attended Charleston’s segregated public schools where white teachers believed themselves racially superior to their students. She helped the NAACP collect signatures of support. “In 1919 we went door to door to ask people if they wanted black teachers to teach their children,” she later recalled, “because the lawmakers said that only the mulattoes wanted these jobs, and they didn't think that the domestic workers and the chauffeurs and the garbage people and the longshoremen wanted black teachers. So we had to do a door-to-door thing to get black teachers to teach their children. . . . I did Calhoun Street from King to the river with some of my students.”

During her years at Avery, Septima Poinsette grew, not only as a teacher, but also as a citizen. Not content with simply earning a better living than her parents and enjoying the benefits of Avery’s more privileged atmosphere, she was determined to make a better learning environment for all Charleston’s Black children.

Images