Overcoming: Septima Clark Meets Personal Challenges, 1920-47

Grieving the death of her infant daughter, a young Septima Poinsette Clark came to the Charleston Battery and almost succumbed to despair. Eventually she overcame her grief and weathered other personal challenges in the next two decades, growing more confident and determined.

Although she was a successful teacher, in her twenties and thirties Septima Poinsette Clark also experienced several difficulties and setbacks. At one point, she was discouraged enough to contemplate suicide. She did not realize, then, how much she had to offer her family and community, and she had no idea that someday, societal challenges she faced might also be overcome.

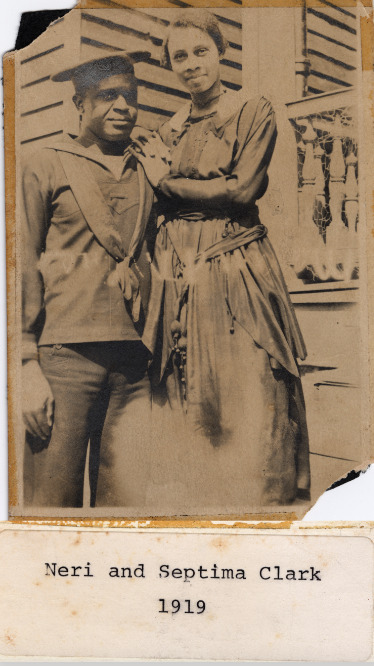

In 1920, Septima Poinsette went against her mother’s wishes to marry a Navy sailor from North Carolina she’d met while volunteering at a club that offered hospitality to soldiers (the “colored” Victory Club at 424 King Street). After the sailor, Mr. Nerie Clark, had asked for her mother’s blessing, but did not receive it, Ms. Poinsette accepted his proposal and married at age 22. “Since I had never fallen in love before, I thought this was my chance. This was my life, so I went ahead with it.”

Their first child was born in 1921. “I called her Victoria for my mother, but she didn’t live but twenty-three days,” Ms. Clark later recalled, decades later. “I felt sure that it was my sin that caused that. I had disobeyed my mother, and I thought that’s why this baby didn’t live. I went down on the Battery, and I thought so much about drowning myself. My mother must have thought about it, too, because she sent my brother on a bicycle to look for me. He found me sitting down there. I changed my mind, I guess, and came home.”

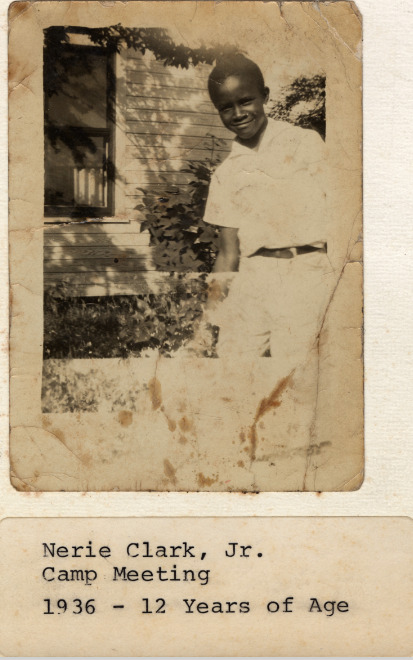

After her family’s intervention, Ms. Clark continued grieving. “My husband was at sea at that time. That’s what made me feel so terrible about it. We buried that baby, and when he came back I had to tell him about it, which was sad. There was nothing else I could do. Right after that we left and went to North Carolina to his people, and I got pregnant again.” The Clarks moved to Dayton, Ohio, where their second child, Nerie, Jr., was born in 1925. More heartbreak followed when she discovered her husband was having an affair. She and Nerie, Jr. moved in with her in-laws in North Carolina. Ten months later, she was called back to Ohio “to say goodbye to my deeply ashamed husband” who was dying from kidney disease. Decades later, "Ready from Within" disclosed how difficult this had been for Clark. “I took his body home for burial and pieced together all the sweet notes he had written me, so the minister could help the family feel good. The casket lay in his mother’s living room, and his ten-month-old son, just learning to walk, swung on the handles as if it were a toy.”

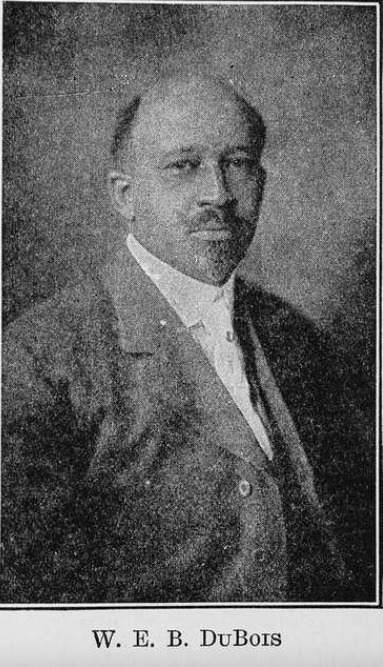

Dedicated to her son, Ms. Clark kept going. She returned to Promise Land School to teach in 1927. Nerie Jr. became ill while living on Johns Island, and Ms. Clark sent him to her in-laws’ to live. In 1929 she moved to Columbia, SC. “I hated to give up my work on Johns Island, but I was a widow with a young son, and I knew I must look ahead. I had been attending summer school in Columbia during the vacation months, and I knew that salaries for teachers there were $65 a month.” There, she taught while continuing to pursue a bachelor’s degree. “You know, segregation caused us to have double sessions [in overcrowded Black schools]. And I taught from twelve o'clock in the day till five in the afternoon. And in the mornings I could take two or three classes at one college, because I was in a college town, and at night I could take two or three more.” She also took summer courses, even though that limited the time she could spend with Nerie, Jr. “It caused me a lot of sorrow to decide to leave my son with his grandparents. I hated it so much. But I had to go teach, and I used to cry every time. When I went to summer school, pulling up my credits, it was hard for me to leave him.” She took a memorable summer course at Atlanta University with Black intellectual and activist W. E. B. Du Bois. During a class discussion, she described having come to class on a streetcar and seeing a Black mother having to tell her young son he could not sit in the front . Du Bois responded to Ms. Clark’s story by telling the class that “there will come a time when this will be changed.”

While living in Columbia, Ms. Clark became more self-confident, feeling that she “could mix with people that I couldn’t in Charleston because my father was a former slave and my mother took in laundry. Columbia was more democratic. There I learned to feel comfortable with middle-class people, even though I never really considered myself a middle-class person.” Wishing to provide more for her son, and “to buy a house for my parents,” she continued to work extra jobs; even in Columbia, Black teachers made far less than their white counterparts. One summer she worked at a camp in Maine, “and it cleared my money that I made in the winter.”

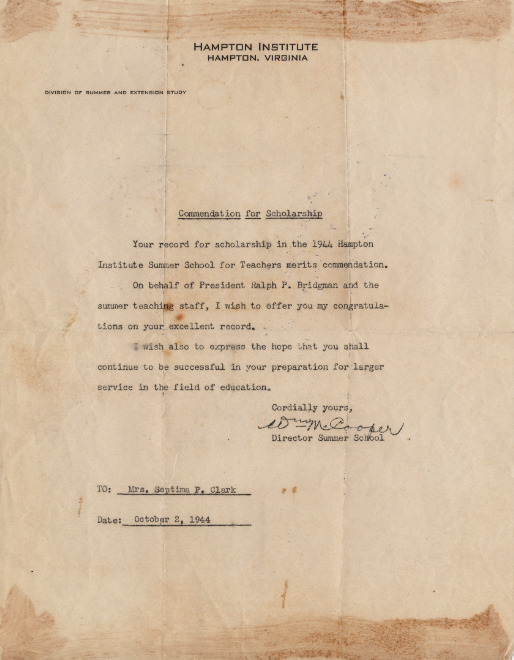

Clark earned her bachelor’s degree from Benedict College in Columbia in 1942, and in 1946, earned an M. A. from Hampton Institute. During eighteen years in Columbia, she improved her financial position greatly. “When I left . . . my salary had advanced from $780 a year to almost $4000 a year,” she recalled.

She decided to leave after her mother suffered a stroke. For months, Ms. Clark traveled to Charleston every weekend to care for her before deciding to move back. “Coming down from Columbia at that time on the bus was hard. Segregation was at its height. I would get on a bus in the afternoon, and no matter how long the trip you could never use a bathroom. . . . I said to myself, ‘Now, we’ve got to do something about these things,’ and that’s what I did for the next twenty-four years.” Having moved away from Charleston as a grieving young wife, Ms. Clark returned in 1947 as a loyal daughter and an accomplished, determined woman.

Images