Activism : Pay Equalization and Septima Clark's Home, 1929-48

The Clark family lived on this block of Henrietta Street for decades before Clark could afford to buy a house. Living in Columbia, Ms. Clark developed skills as a teacher-activist and participated in the NAACP’s pay equalization campaign. As a result, her salary grew, enabling her to buy her family a home.

Purchasing a house on Henrietta Street in 1948 was the fulfillment of a lifelong dream for the fifty-year-old Septima Clark. Since childhood, she’d wanted to give her parents a more comfortable existence. Clark would not have been able to buy this home, however, if court decisions in the 1940s had not changed South Carolina’s practice of paying Black teachers far less than their white counterparts. While in Columbia, Clark participated in the movement for pay equalization which would ultimately give her the opportunity to triple her salary.

Before the movement succeeded, Clark supplemented her income by occasionally teaching evening classes in Columbia, a job that made her more adept at teaching adults to read and write. She taught in Richland County’s progressive Adult Schools program and, at Fort Jackson, worked with Black soldiers who could not sign their own paychecks. Her professional skills were also enhanced by an organization for Black teachers, the Palmetto State Teachers’ Association, whose members shared ideas and practical techniques. Moreover, PSTA believed in teaching students to become active citizens—informed participants in local governments. This was a bold and visionary attitude in a time when few Black South Carolinians were able to vote. When Clark attended large meetings of the PSTA, as she later recalled in her memoir, “we teachers had a visible demonstration of our importance, of what we already were; it didn’t take much to imagine what we might be.”

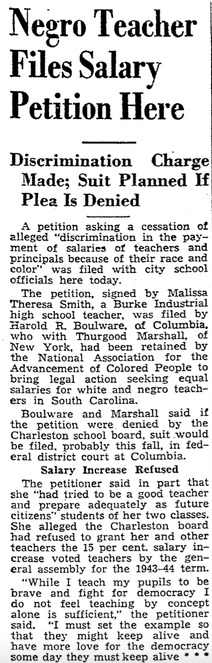

Most PSTA members, like many other Black professionals in Columbia, would not risk their jobs by protesting against state laws. But Clark eagerly supported the NAACP when it challenged the state’s practice of paying lower salaries to teachers who were Black. The PSTA and others did not believe the NAACP campaign for salary equalization could succeed. Clark, however, went door to door recruiting new NAACP members, trying to convince community members and colleagues that they should pursue the issue.

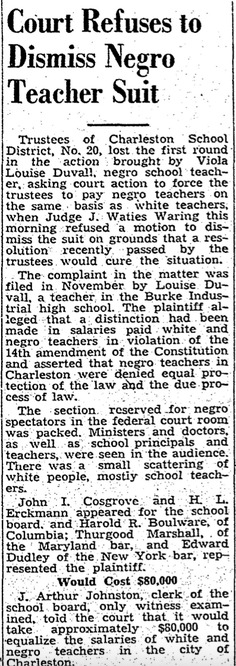

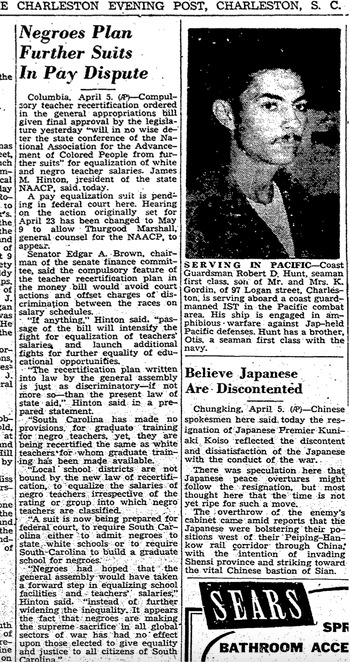

In a 1940 case (Alston vs. School Board of Norfolk), federal courts had ruled that “separate but equal” institutions must actually be equal. However, in South Carolina in 1942-43, white teachers’ average salary was twice what Black teachers earned ($1091 vs. $538). Clark helped document some of these inequities in Columbia. “I was able to get some affidavits from both white and black teachers about salaries and show the discrepancies.” In 1943, the NAACP sued the Charleston school board. Future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall argued for the NAACP; C of C graduate Harold Erckmann represented the school board. The Federal Judge hearing the case was C of C graduate J. Waties Waring, a prominent Charlestonian. He surprised everyone by ruling that the city must equalize its teachers’ salaries.

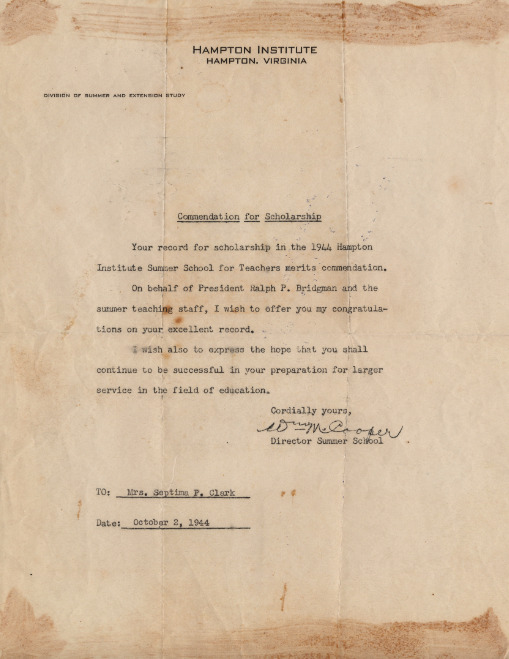

In another NAACP lawsuit in 1945, Waring ordered Richland County to set a new salary schedule to equalize pay. In response, the state created a rating system for teachers based on their years of education and score on a state exam. Many Black teachers objected to the exam, which they felt might disadvantage teachers who hadn’t had a chance to complete college or graduate school (in that era, a teacher’s license did not require a college degree). Clark, who had earned a licentiate of instruction, but not a B.A., from Avery Normal Institute, had been taking additional college courses, which helped prepare her for the state teachers’ exam. She had earned a B.A. (1942) and an M.A. (1946), and she’d received strong professional development training in the Columbia schools where she worked. She scored high on the exam, tripling her salary.

Clark’s political activism, along with hard work and talent, increased her earning power. Although not wealthy, she could now afford a house for her Charleston family. As a child, when her father “didn't have money enough to buy a number of things that we needed, he would talk about how he hated that.” Clark's mother often told her children about wearing nicer clothes before she had children to support. “I can remember her singing those blues so well, talking about the things that she had, she'd never have anymore. She hated it very much. But she did get to the place where she could have everything that she wanted. . . . I bought a house and I had it repaired, down on Henrietta Street, and the night that we had the opening, oh, she was most jubilant. . . . And she just threw her arms around me and said, ‘Nice, nice to do this.’” Clark had added a downstairs bedroom and bathroom so that her mother “wouldn't have to climb steps. . . That's what I did when I was able to. . . . She was too happy, but I was hoping that my father could have been alive. I would have liked for him to have been there at the time. But he was gone.”

Images