Allies: Crossing the Color Line with Septima Clark, 1947-1956

Black women were leaders at the Coming Street YWCA. After returning to Charleston, Clark tackled community problems, working with Black women’s clubs and white allies who opposed segregation. When fired from her Charleston teaching job for belonging to the NAACP, she became director of workshops for activists at Highlander Folk School in TN.

In 1950, Charlestonians were shocked by a speech made at the Coming Street YWCA, denouncing segregation. A well-known, affluent white woman named Elizabeth Waring delivered the speech. The ensuing backlash typified the growing resistance to a racially integrated society that Septima Clark and white allies encountered during the 1950s, within and beyond Charleston.

After returning to her hometown in 1947, Ms. Clark found a job teaching the morning session at Archer Elementary School. (Schools for Black students in Charleston, like those in Columbia, were so crowded they had to hold double sessions.) Her afternoons were devoted to community service. Ms. Clark became president of the Gamma Xi Omega chapter of the Alpha Kappa Alpha (AKA) sorority, a service organization of Black collegiate women. She served as president of the city’s Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs and was chair of the Coming Street YWCA, the city’s Black branch, which provided recreation, kindergarten, and services for working Black women.

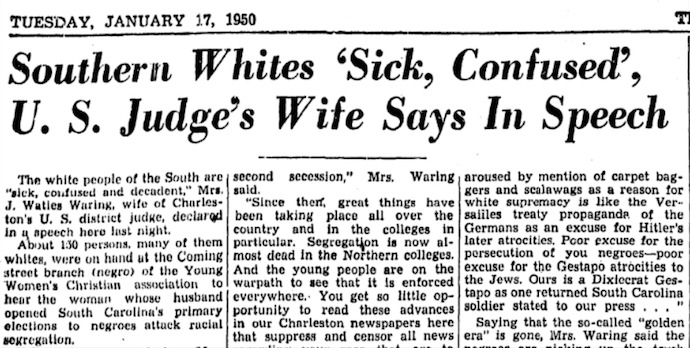

In 1950, the Coming Street YWCA invited Elizabeth Waring to speak at its annual meeting. Many white Charlestonians hated Elizabeth Waring and her husband, Judge Julius Waties Waring, because of his court rulings--that South Carolina schools should equalize pay for Black and white teachers, that Black students should be able to attend a state law school, and that Blacks must be allowed to vote in Democratic primaries. Additionally, the Warings had fallen in love while married to others; Judge Waring’s first wife was a prominent Charlestonian. The scandal gave most whites another reason to despise the Warings, besides the couple’s outspoken opposition to white supremacy.

When Charleston newspapers announced Elizabeth Waring would be speaking to a Black audience on Coming Street, members of the white Society Street YWCA were uneasy. Fearing controversy, the white Y members asked the Coming Street Y to disinvite Mrs. Waring. Instead of complying with this request, Septima Clark called on the Warings in their Meeting Street home and encouraged Elizabeth Waring to give the speech, which she did. Waring told the Coming Street Y audience that white Southerners were “sick, confused, and decadent people.” She urged Blacks to vote and stand up for their rights, saying, “You are building and creating. The White Supremacists are destroying and withholding.” Waring’s words seemed so radical that when Clark’s mother heard them at the event, she collapsed.

Newspaper coverage of the speech heightened the animosity most whites felt for the Warings, but Septima Clark and other Black leaders became friends with the couple, who frequently invited them to dine at their home. Clark later mused that the Warings’ invitations may have improved her own standing among more affluent Blacks. In any case, these social events crossed a color line, since Blacks were expected to enter whites’ homes only as servants, never as guests. Clark was pleased when Elizabeth Waring accepted Clark’s invitation to tea at her Henrietta Street home, even though Mrs. Poinsette, mistrustful of whites, refused to come out of her room during the visit. Meanwhile, elected officials and white citizens continued calling for the Warings to leave the state. They did leave in 1952, moving to New York after threats and physical attacks on their Charleston home, but they remained lifelong friends with Clark and other Black leaders.

Allies also were at work elsewhere in the South. In 1952 the director of the Coming Street Y, Ms. Anna Kelly, attended a workshop on school desegregation in Monteagle, TN at the Highlander Folk School, a training center for social activists. Kelly reported on the event to Clark, who went to Highlander in summer 1954. Clark was “really surprised” by this organization’s integrated workshops, at which “a white woman would sleep in the same room that I slept in, or eat at the same table.” Highlander’s grassroots approach to social change was in keeping with Clark’s philosophy of educating people to make their own decisions and fight their own battles. She recruited other Lowcountry leaders to attend Highlander, and in 1955, she was hired to lead summer workshops. At one workshop, two Black Lowcountry leaders, Esau Jenkins and Bernice Robinson, began planning an education center for illiterate adults on Johns Island--a “citizenship school” that would later become the model for programs across the South.

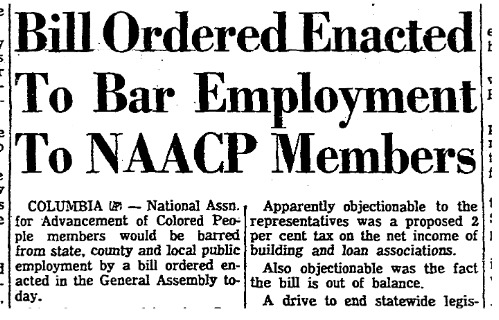

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled school desegregation unconstitutional in Brown vs. Board of Education, a case that included an NAACP lawsuit against a South Carolina school board. Few whites in the South supported this ruling; instead, most were horrified at another attack on segregation and white supremacy, which they called “the southern way of life.” South Carolina KKK chapters gained hundreds of new members at meetings patrolled by state troopers. Southern communities also formed all-white “Citizens’ Councils” to maintain segregation, albeit in less overtly violent ways. To the Charleston News and Courier, the Charleston Citizens’ Council contained “the best people,” but Charleston’s NAACP president Joe Brown called it “the tuxedo gang of the Ku Klux Klan.”

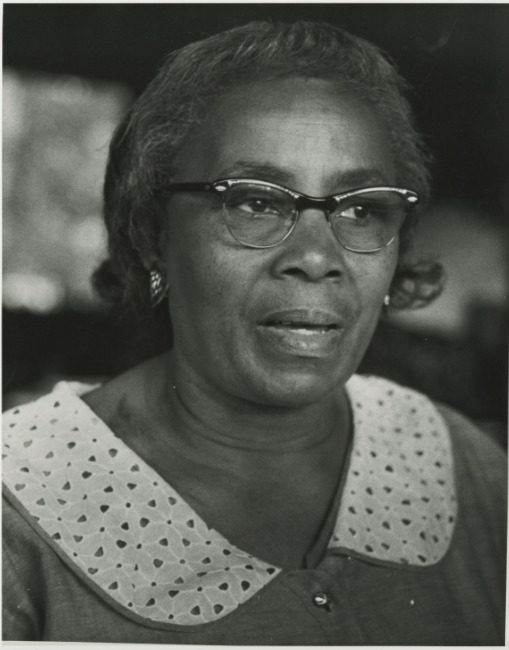

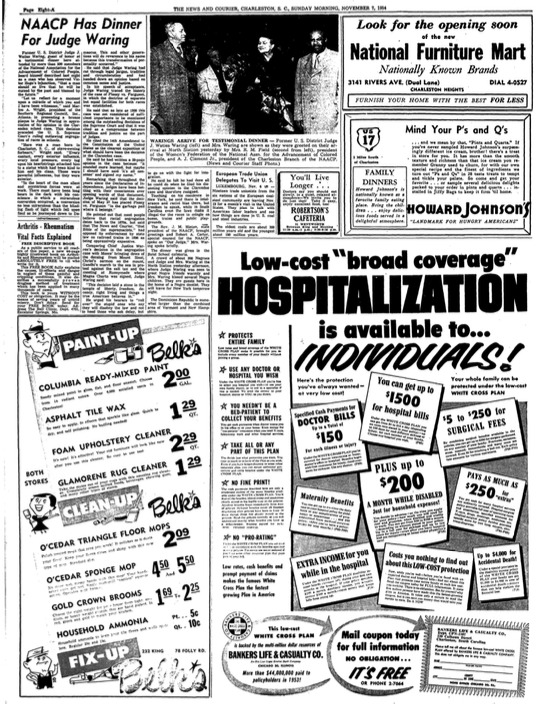

In 1956, South Carolina barred city, county, or state employees from belonging to the NAACP. Many Black educators felt they had no choice but to withdraw their NAACP membership, but Clark and a handful of other teachers refused to do so. In May 1956, she was fired by the Charleston school district. She contacted hundreds of colleagues, asking them to protest, but only five showed up for a meeting at the superintendent’s office. Years later, Clark reflected, “I think I tried to push them into something they weren’t ready for. . . .You always have to get the people with you. You can’t just force them into things.” Other Black Charlestonians feared backlash if they supported Clark publicly. That December, when her AKA sorority held an appreciation dinner for Clark, only a few members would pose for a photograph with her. “If they had, they would have lost their jobs,” she recalled.

Highlander hired Clark to work full-time as the center’s director of workshops in 1956. White allies at Highlander also faced opposition. State officials in Tennessee opposed the center because of its interracial, pro-integration gatherings, and they temporarily shut down Highlander in 1961. This setback did not stop Clark’s work. Instead, she began implementing another citizenship education program on behalf of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Images