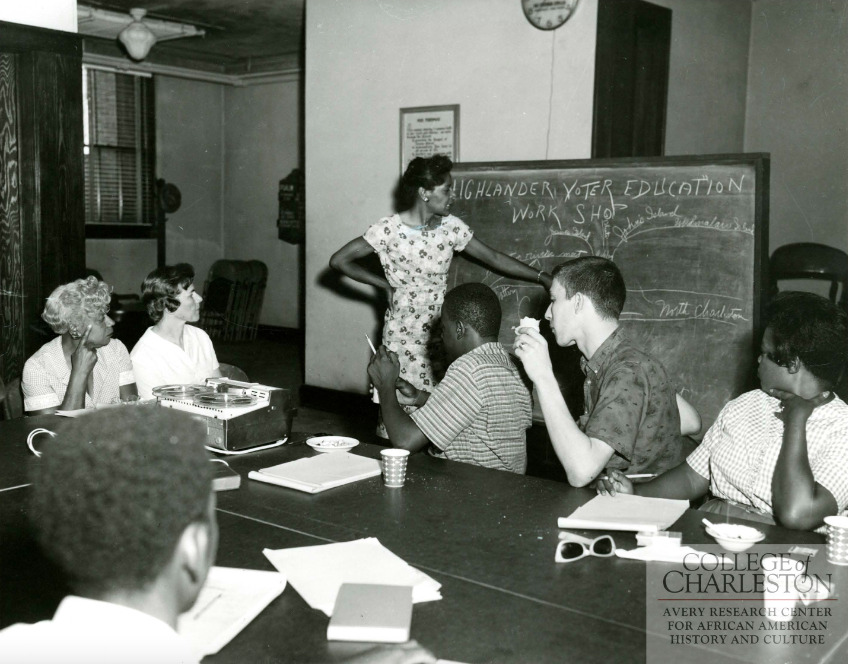

Leadership : Septima Clark's Faith Helps Change the Lowcountry, 1954-1964

Inspired by her faith, Clark worked with Bernice Robinson and Esau Jenkins to develop a “citizenship school,” teaching Black adults on Johns Island to read, register to vote, and become active citizens. The program spread across the Lowcountry.

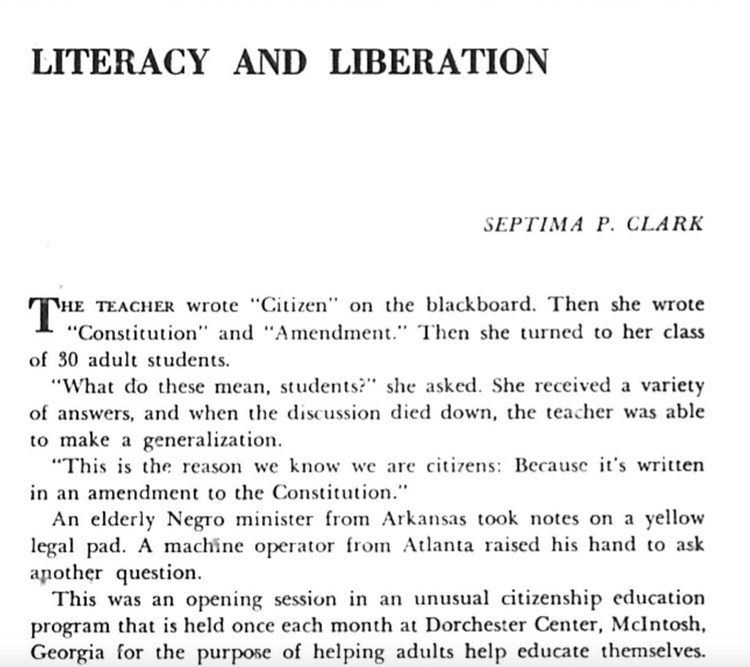

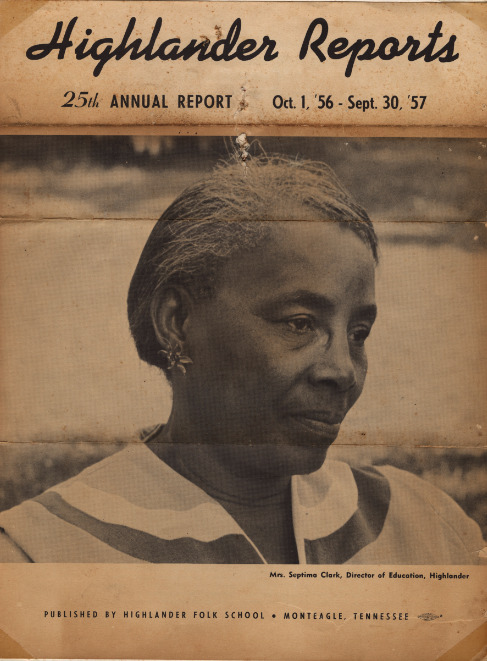

In 1956 Septima Clark began working full-time at Highlander Folk School, and in 1961, took a job with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. During these years she maintained her membership at Old Bethel United Methodist Church, a few steps from the College of Charleston. Clark regarded her activism as an extension of her Christian faith. As she stated in a 1964 essay, “Where there is obedience to the gospel, there will be concern for the less fortunate. . . The Christian can never be content with token progress by a fortunate few.”

While her activism now extended across the South, Clark continued to support her Charleston congregation. A 1964 letter to Bernice Robinson closes, “Please put this contribution in church for me next Sunday.” The rest of Clark’s letter reported on the progress of an innovative program teaching Black adults to read, write, and register to vote. “I’m enjoying the work. It’s challenging,” Clark wrote Robinson.

The work was a “Citizenship School” program that changed the Lowcountry and eventually, the South. It was begun in the 1950s by Clark, Robinson, and Johns Island native Esau Jenkins. The school was an outgrowth of the Progressive Club, a Black mutual aid society that provided community support, including legal aid for victims of racial violence. Throughout the South, white violence against Blacks often went unpunished, as in the notorious case of Emmett Till’s murder in Mississippi in August 1956: an all-white jury swiftly acquitted his killers, who later confessed to Look magazine. Violence also occurred in the Lowcountry; on Johns Island in the 1930s, a white man, after shooting a Black man for accidentally running over his dog, was not held accountable. The Progressive Club formed in response to this incident and other inequities on Johns Island. Government services available to whites, such as school bus transportation or access to a local high school, were not available to Black Johns Islanders. Those who could not read and write could not tell whether they were being cheated while making purchases or paying their taxes or insurance premiums.

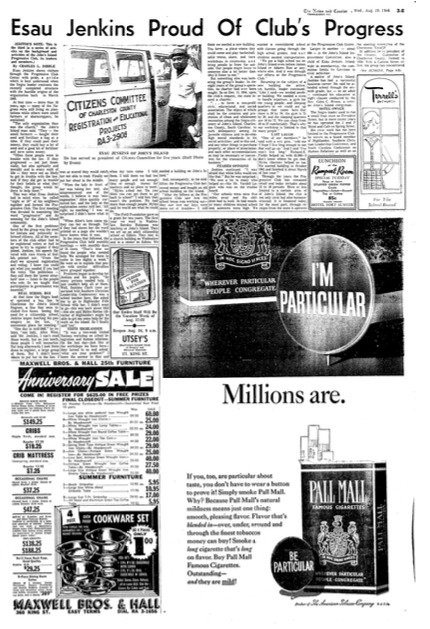

Esau Jenkins was determined to change things for his community. Few Black residents could vote and influence public policy; white officials controlled the voter registration process and would not let Black citizens register if they could not read or explain the state constitution. Jenkins and his wife Janie Jenkins ran a service transporting people to downtown Charleston, and as he drove, he conducted informal classes for his passengers, helping them learn what they’d need to know to register. On his VW van was the Progressive Club’s motto: “Love is progress. Hate is expensive.”

In 1955, Clark, who had first met Mr. Jenkins when teaching on Johns Island in the 1920s, recruited him to attend a summer workshop she was directing at Highlander Folk School. They began developing plans for a citizenship school for Johns Island. Clark, Bernice Robinson and Jenkins recruited participants for their first classes, taught by Robinson, in January 1957. Highlander advanced Jenkins the funds to purchase an old school building, and the new school was soon underway.

By 1958, other citizenship schools were formed, in North Charleston and on Wadmalaw and Edisto Islands. Two more soon opened on St. Helena and Daufuskie Islands. At these schools, adult students learned to read letters from relatives, fill out a money order form, determine how much tax they owed and pay it themselves. Hundreds of Black citizens were now able to register to vote. Some got Social Security benefits and developed skills needed to run their own businesses. In addition to classes, schools held meetings where people discussed current events, community needs, and how to address these needs.

The school on Johns Island initially operated quietly--a grocery store at the front of the Progressive Club partly concealed the classes being held in the back room, which might have attracted more suspicion. Eventually, though, word of the schools spread, and the Charleston News and Courier began to write about them, noting that this form of citizenship might affect political leaders. A 1959 editorial warned, “Should a Negro bloc vote develop in the South. . . . white Southern politicians would seek it. The kind of politicians who court the Negro vote will not provide the best government for either race.” The editorial also suggested that the citizenship school might be a Communist organization. “White civilization. . . is in peril,” the editorial stated. It closed with a quotation intended to raise concern among white readers: “As Esau Jenkins said of integration, ‘It’s a revolution.’”

The newspaper’s response was not uncommon. Many white in the Souths who wished to keep their society segregated believed proponents of integration were dangerous, anti-American Communists. Segregationists distrusted organizations like Highlander, whose workshops were integrated. In 1959, Tennessee officials, accompanied by photographers, staged a raid on Highlander while Clark was running a workshop there. Clark and several others were taken to jail and charged with possessing and selling whiskey. Photographs of Clark under arrest were published in newspapers, although she was later cleared of all charges.

Highlander was forced to close temporarily in 1961, but soon reopened. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference decided to expand the citizenship schools program and hired Clark. In the Lowcountry, citizenship schools continued serving local people, but also expanded their mission. People from other areas hoping to implement schools and empower citizens in their own communities came to Johns Island to be trained. The Lowcountry’s program had become a model for the rest of the country.

Images

Avery Research Center