Courage: Septima Clark Inspires Nonviolent Resistance, 1960-1965

The Kress store in Charleston was one of many sites across the South where activists risked their jobs and their safety by protesting against segregation and registering Black citizens to vote. Many participating in the civil rights movement were inspired by Septima Clark’s citizenship schools.

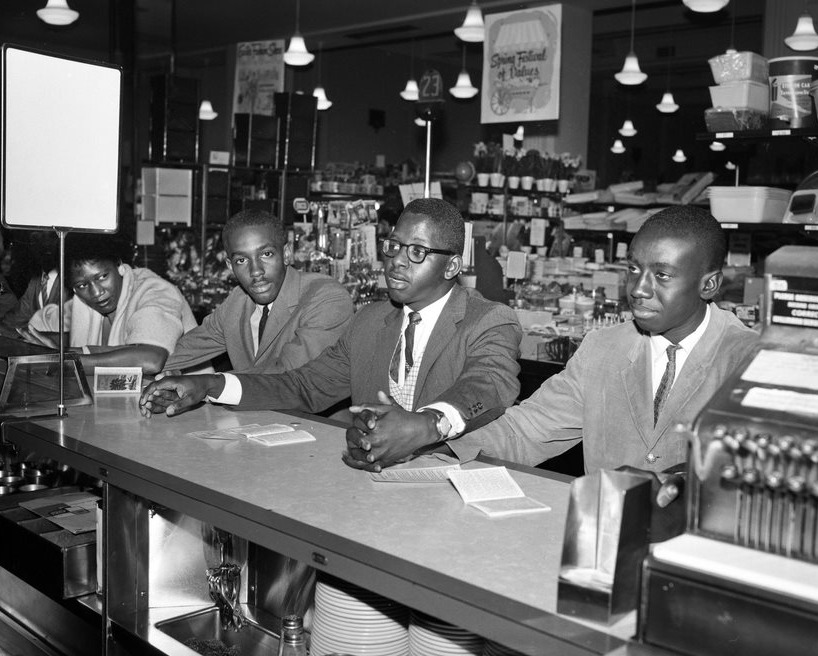

In 1960 on Charleston’s King Street, high school students challenged the longstanding Southern custom that Black citizens could not sit at lunch counters where whites were served. All across the South, similar scenes were playing out: Black customers would quietly “sit in” at a segregated restaurant, knowing they’d likely be arrested for allegedly trespassing or disturbing the peace. Angry white onlookers could become violent. Some of the Charleston students didn’t tell their parents they’d be protesting and facing jail; white employers might fire protestors or family members for their activism.

While these sit-ins were occurring, Septima Clark was continuing to lead workshops and adult education classes for people who wanted to combat racial discrimination. These classes inspired some of their students to take the risk of resisting segregation. One famous protestor, Rosa Parks, took a class with Septima Clark. One famous protestor, Rosa Parks, had taken a class with Septima Clark. Before Parks refused to give up her seat to a white bus passenger in 1955, Clark had taught her in a workshop at Highlander Folk School, where other Lowcountry residents, Bernice Robinson and Esau Jenkins, were making plans for a citizenship school on Johns Island. During group discussions, Clark encouraged the shy Parks to share her struggles with segregation laws in Montgomery. As Clark later said of her approach to teaching, “I always felt that if you were going to develop other people, you don’t talk for them. You train them to do their own talking.” Parks decided to resist laws she once thought could not be changed. Her 1955 arrest triggered the Montgomery bus boycott, initiated by Jo Ann Robinson and led by 26-year-old Martin Luther King, Jr.

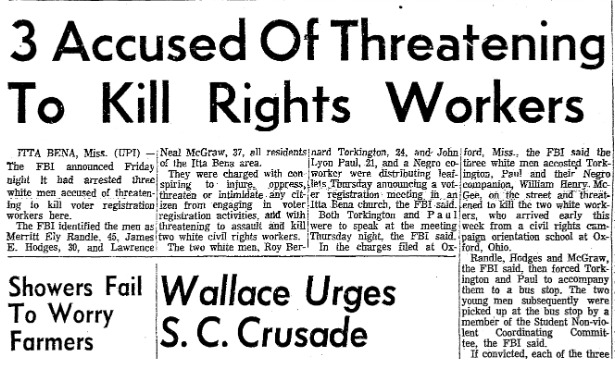

Since 1957, Clark’s citizenship schools in South Carolina had thwarted the laws that were designed to prevent Blacks from voting there. Similar laws were in place across the South, and activists came to Highlander and to Johns Island to learn how to overcome voting barriers with their own citizenship schools. Septima Clark, an extraordinarily successful teacher and manager, was becoming a well-known figure who would be called “The Mother of Civil Rights Movement.” In 1960 her workshop influenced a group of students who formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and planned the Freedom Rides. Traveling on buses through Southern states, Freedom Riders attempted to desegregate bus station waiting rooms and restaurants, often encountering white mobs waiting to attack them.

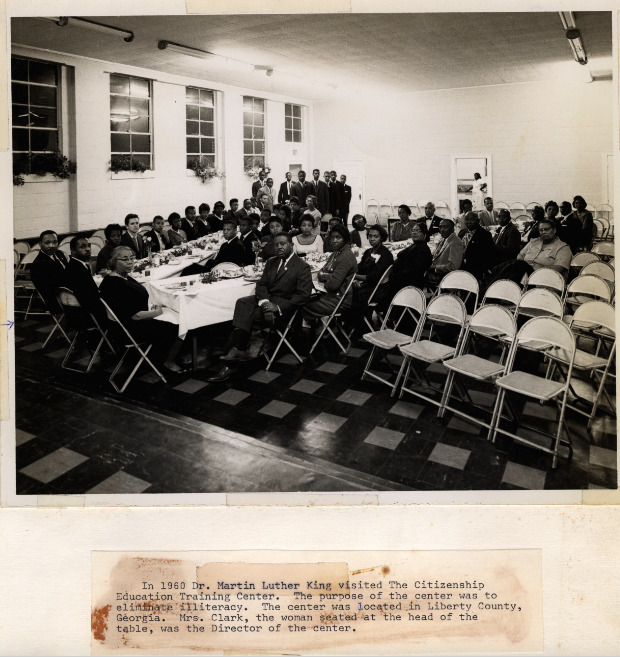

“It was 1962 before the major civil rights groups were ready to do something about voter registration,” Clark later recalled. “But we had developed the ideas of the Citizenship Schools between 1957 and 1961. So all the civil rights groups could use our kind of approach, because we knew it worked.” In 1961, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) recognized the power of the citizenship schools program. The SCLC hired Clark to work with staff member Andrew Young to go to more communities in the Deep South, recruiting and training local people to start their own schools.

Citizenship schools were a crucial component in civil rights activism. “One time I heard Andy Young say that the Citizenship Schools were the base on which the whole civil rights movement was built,” Clark reflected years later. “And that’s probably very much true. . . because the Citizenship Schools made people aware of the political situation in their areas.” Adults who had been excluded from many aspects of modern life grew more confident as they developed their reading and writing skills and could register to vote, pay their own taxes, read the Bible or write family members. They studied the laws of their state and of the United States, learning what rights all citizens are entitled to. Their newfound knowledge helped them register to vote, but also helped them analyze issues and decide how to participate in their communities. In 1962, as the program gained momentum, Clark wrote, “It is evident that we now have within our grasp a new kind of society, a learning society made up of educative communities.”

By 1965, 25,000 students had participated in the Citizenship Schools, taught by 1,600 teachers trained by the SCLC’s program. More than 50,000 new Black voters were registered in the South. As Martin Luther King put it in his “I Have a Dream” speech, “Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy.” To Clark, literacy was not just the ability to read, but also the ability to analyze and interpret one’s society. Educated citizens took these civic lessons to heart. Clark wrote in 1964, “There are many ways to communicate injustices to the American public. These dramatic confrontations were necessary to educate white people in Savannah, Georgia and to make Negroes free enough to vote wisely and speak out. . . Literacy means liberation.”

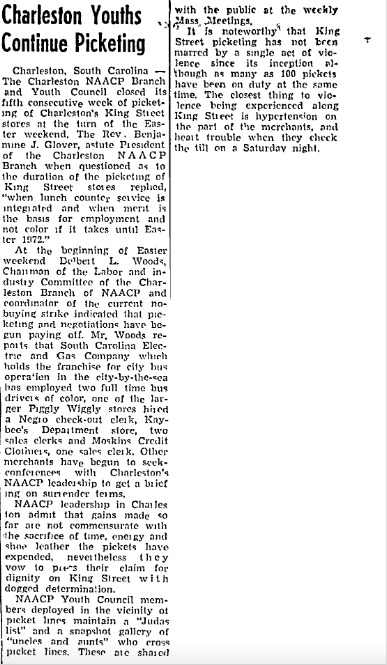

Across the South, thousands joined in civil rights protests and demonstrations. Charleston teenagers sat in at the Kress lunch counter, a block from the College of Charleston. They participated in demonstrations, mass meetings, King Street store boycotts, and the desegregation of the municipal golf course. A few brave students, such as Millicent Brown, began the lonely process of desegregating Charleston’s all-white public schools. (The College of Charleston remained all-white, having become a private school in 1949 to avoid complying with federal requirements for integrated public schools.) Elsewhere, police with billy clubs and snarling dogs attacked protestors who were marching or trying to register to vote. Violence could kill or maim protestors, who did not fight back. They were arrested, beaten, shot, and firebombed. “I was in a Baptist church in Grenada, Mississippi,” Clark recalled years later. “We were talking about registration and voting; we were going to show them how to fill in these blanks. Just as we finished up that meeting and walked out of church, it caught fire in every corner. . . This just shows how mean people can be.”

When the American public saw nonviolent citizens facing violence for exercising their citizenship rights, it became clearer that segregation, allegedly “the Southern way of life,” was not a peaceful local custom, but an inherently violent system. By 1964, the movement was beginning to change the country. Congress passed President Lyndon Johnson’s Civil Rights Act, banning racial discrimination in federally funded programs and in public accommodations. King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and Clark traveled to Norway with other leaders to see him receive the award.

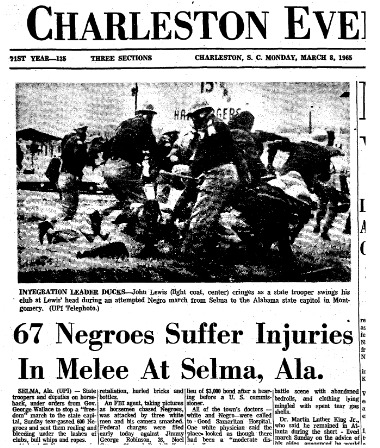

More dangers awaited civil rights activists. They continued getting into what John Lewis would later call “good trouble,” facing danger and arrest while exposing the flaws of an unjust society. Lewis and other peaceful demonstrators paid a high price for their ideals on “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Alabama in March 1965, when crowds marching across the Edmund Pettus Bridge were brutally beaten by police as the world watched on television. Shortly thereafter, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act that eliminated many barriers to voting. Great strides had been made, but Clark and other activists knew their work was not done. More advocacy and more citizenship education would be needed for people to address their communities’ problems.

Images