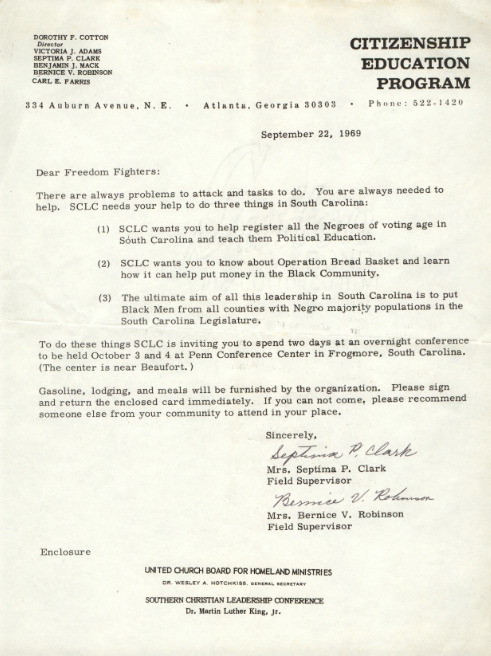

Persistence: Septima Clark Combats Poverty and Injustice, 1965-1970

Black hospital workers and their supporters protested unequal treatment at the Medical College on Rutledge Avenue. The Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts were great achievements, but other problems remained. As a staff member for the SCLC, Septima Clark continued to fight racial discrimination and economic inequities.

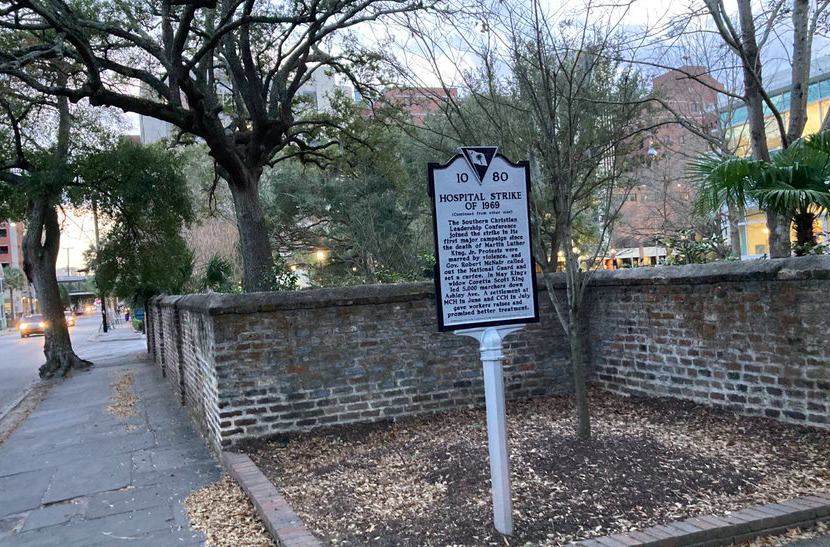

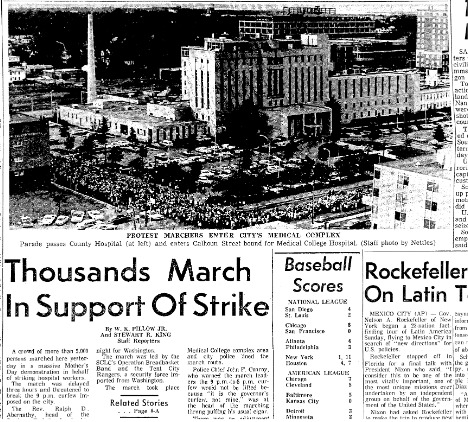

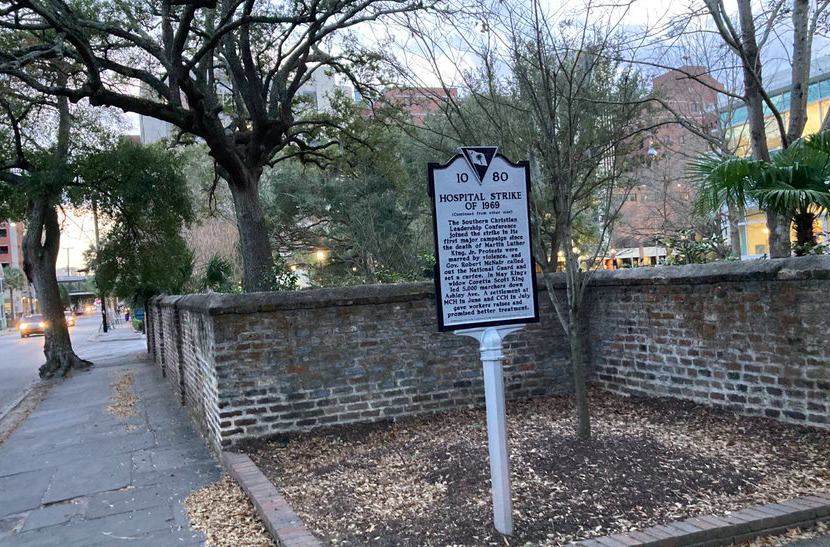

The Medical College of South Carolina was one site where activism continued after the Civil Rights Act. In 1969, Septima Clark and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) supported the hospital workers’ strike here. Workers, primarily Black women, filled the streets along with their supporters, demanding better pay and working conditions. The Medical College president told reporters, “I just don’t believe it’s a civil rights issue.” To Clark and her colleagues in the SCLC, however, supporting the strike was a continuation of their ongoing work fighting for the rights and dignity of Black citizens.

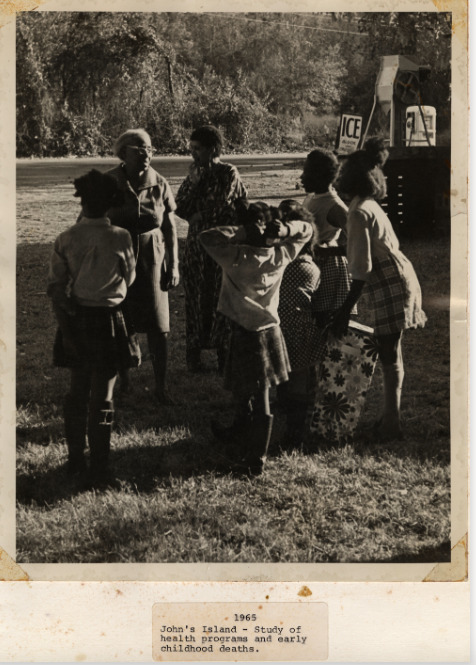

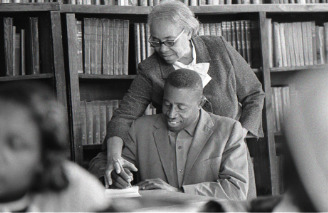

Since 1961, Clark had been on staff at the SCLC as it worked for desegregation and voting rights under King’s leadership. The SCLC shifted focus after the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965. States could no longer legally require citizens to interpret their state constitution to register to vote, and citizenship schools no longer needed to coach students to surmount this barrier. The SCLC got voters registered, encouraged voter turnout, and promoted programs sponsored by President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. People who had been trained in citizenship schools, like Ethel Grimball on Wadmalaw Island, began working in Head Start programs. The SCLC also publicized systemic inequities that prevented individuals from accumulating economic and social capital. As King began speaking out on these matters, some journalists and public officials criticized him, saying he was straying from the cause of desegregation, but King responded that poverty and lack of opportunity disproportionately affected Black Americans.

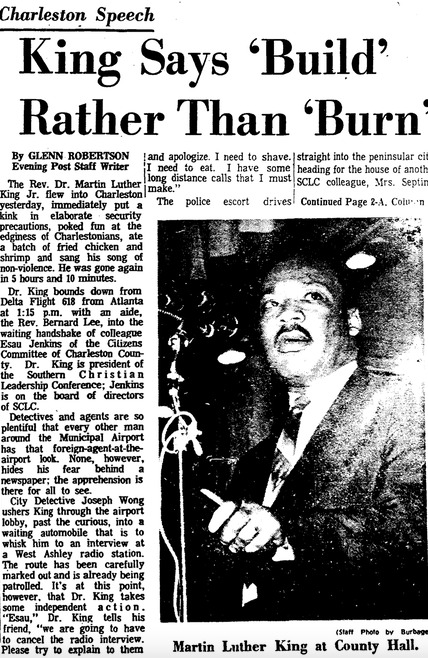

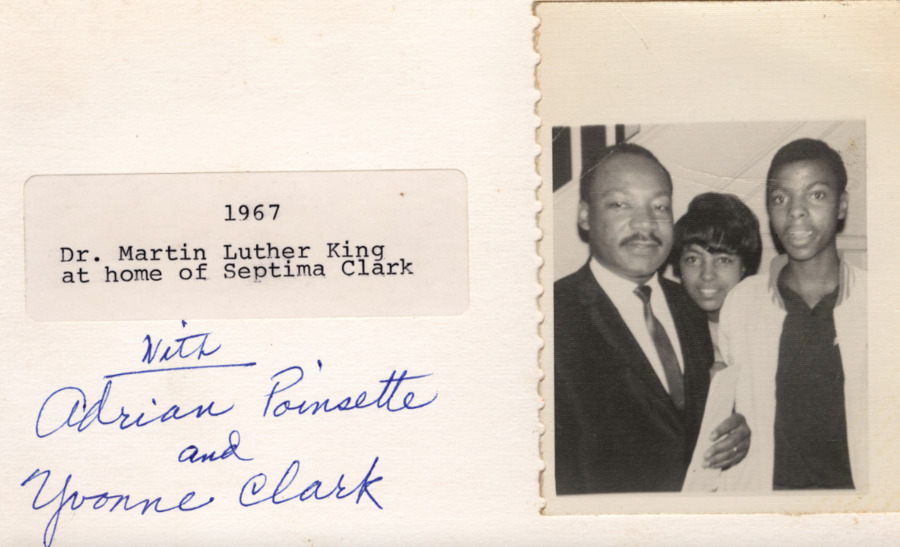

King called for solutions to poverty in a speech he gave in Charleston in 1967. He was introduced by Johns Island activist Esau Jenkins, who had worked with Septima Clark to develop the citizenship school formula that registered many new voters in the South. Before delivering the speech, King stopped at Septima Clark’s home to confer with local leaders. King then gave a speech to over three thousand people, telling the crowd, “Emancipation for the Negro was freedom to hunger.” The War on Poverty, he said, was so underfunded that “it didn’t even end up a good skirmish.” King contended, “It’s possible to end unemployment, it’s possible to end poverty.” He also denounced the US’s war with Vietnam as “the most unjust war in the modern world and maybe in history.” (A recording of King’s speech is at the Avery Research Center.)

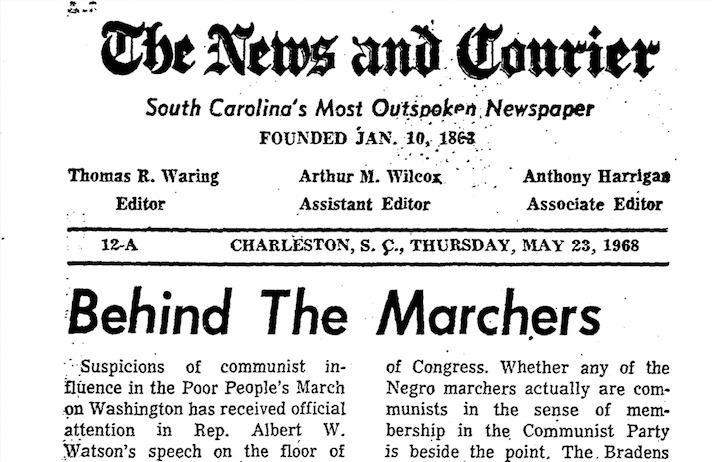

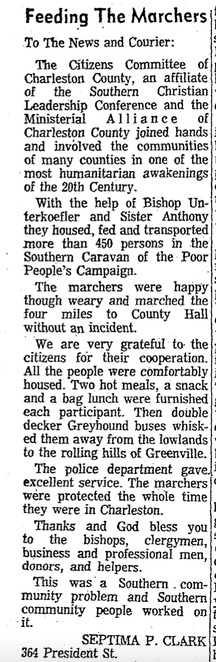

In April 1968, King was assassinated in Memphis, where he was supporting striking sanitation workers. The next month, the SCLC went forward with the Poor People’s Campaign King had helped plan, a mass demonstration in Washington DC calling for more aid to America’s poor. Demonstrators from across the country began traveling to Washington in May. The “Southern Caravan” traveled from Mississippi through the South, including Charleston. Afterwards, the News and Courier’s editorial, “Behind the Marchers,” announced, “Suspicions of Communist influence in the Poor People’s March on Washington has received official attention.” The editorial suggested (incorrectly) that the march might culminate in an attack on the Capitol. Septima Clark's letter to the editor appeared the same day, praising everyone who worked together to keep the event running smoothly and feed the marchers as the caravan came through Charleston. “This was a Southern community problem and Southern community people worked on it,” she asserted.

Community members, including Clark, continued addressing community problems in Charleston, problems that many whites were unaware of. Years later, Andrew Young recalled his experience in 1969 as an SCLC staffer: “It must have come as quite a shock to the white community when a few Black hospital workers attempted to organize a union at the South Carolina Medical College Hospital.” The hospital fired twelve workers they believed were leading the effort, causing 450 more to walk out in protest on March 19, 1969. As Young wrote later, the SCLC came to support the strike because it fit the SCLC’s “desire to combat fundamental economic inequities and was consistent with the long-term aims of the Poor People’s Campaign. In addition, in Septima Clark we had a staff person who knew intimately the personalities and tendencies of black and white leadership in Charleston.”

The strike continued for months. South Carolina’s governor declared a state of emergency and a 9 pm to 5 am curfew, and ordered 1,000 state troopers and National Guardsmen to patrol the city. Workers, family members, and students were arrested nightly at demonstrations held in defiance of the curfew. Coretta Scott King marched with the workers, was arrested, and addressed a mass meeting at Morris Brown AME church. The strike lasted 113 days, until the hospital promised to rehire the fired workers and use a new grievance process for resolving complaints. Some strikers said this was the first time they had received at least some recognition from the hospital. Momentum from the strike also spurred increased Black voter registration in Charleston.

In 1970, in Charleston’s formerly segregated Francis Marion Hotel, Septima Clark was honored with a banquet where the SCLC celebrated her contributions to the civil rights movement. Clark, age 72, was retiring from the SLCC, but was far from finished with her work as an outspoken activist, educator, and leader.

Images