Service: Septima Clark's Continuing Influence, 1970-1980s

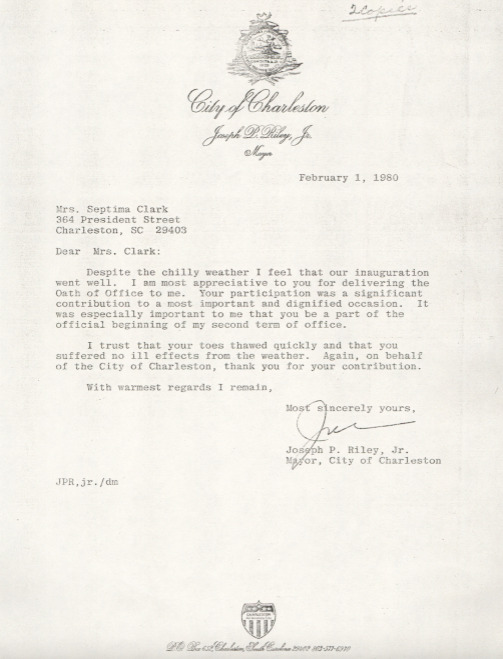

At Charleston’s City Hall in 1980, Septima Clark, an acknowledged leader in Charleston, swore in Mayor Joseph P. Riley for his second term. Now famous, Septima Clark continued to question the status quo and work for justice, encouraging other activists, especially women and young people, to do likewise.

Septima Clark continued addressing injustice and poverty throughout the 1970s and 80s. By this time, more people in her hometown recognized the value of her activism. “People were so afraid of me before,” Clark told an interviewer in 1976. “Now my preacher talked about me one Sunday. He was talking about things going different with God, and he mentioned my name.” Joseph P. Riley amplified this recognition by inviting Clark to mark the beginning of his second term as mayor, having once again been elected by a coalition of Black voters and white progressives. In January 1980, Septima Clark was now one Charleston’s most prominent Black leaders. The daughter of a former slave, she administered the oath of office to the city’s mayor on the steps of City Hall, a structure enslaved labor had helped to build in the early 1800s.

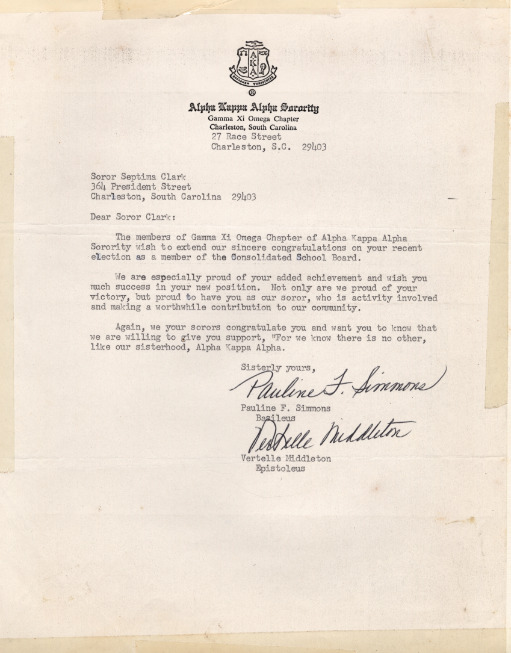

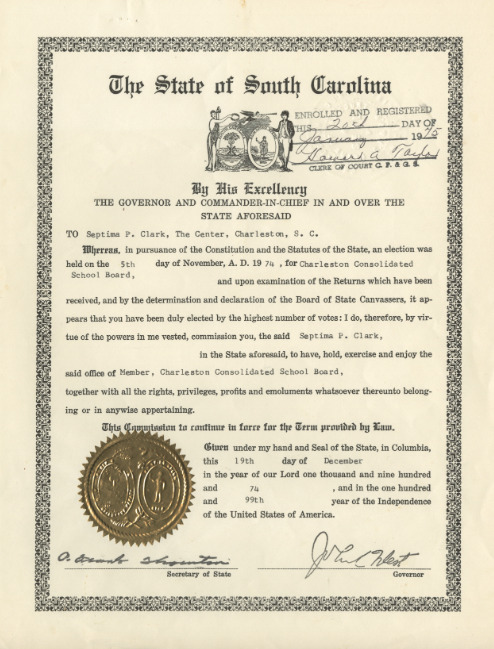

Since retiring from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1970, Clark had continued to work on local issues, including public health, food stamps, and day care to support working families. In 1974 she was elected to the Charleston County School Board, the same body that had fired her in 1956. As a Board member, she advocated for Black teachers and students whose needs were not always recognized by white Board members or in curricular materials. When the Board reviewed a booklet on American government in 1981, Clark noted that no Black people were represented there. “I wanted to know who the black children would have to look up to in that book,” she said. “There was nothing in there that would help black children to feel that they had a right to the tree of life, and I know how important that is."

Clark continued, “Our children. . . also need to know how change comes about. You have to develop them to do their own thinking and not accept unjust things but break through those things and change them. . . . There is a young [teacher] who has been talking to her children about standing up for their rights, and her name is on the list to be terminated. I don’t want to miss that meeting Monday, because I’m going to vote on her to stay in that school. [. . .] They’re going to try to fire her, but I’m going to fight them.”

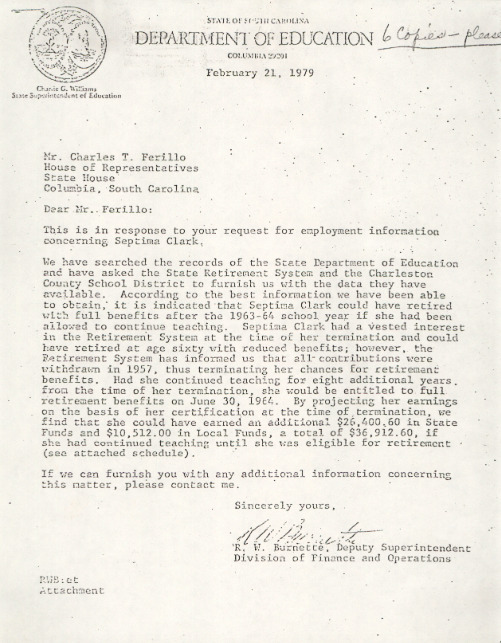

Although she was never wealthy and sometimes short of funds, Clark continued to give financial assistance to many young people, believing that if she did not, she “might refuse the very one who’s going to do well.” When Johns Island activist Bill Saunders asked Clark for help finding a room downtown for his daughter, a College of Charleston student, Clark offered to share her own bedroom. She also continued caring for family members. Her “grands” sometimes lived with her, including a grandson with disabilities. “My son’s grandmother kept him, so I had his little boy,” she said. Her financial challenges were slightly eased in 1976 when the state of South Carolina began paying Clark the pension she would have received if she had not been unjustly fired in 1956. In 1981 the state paid her another $15,000, half of the pension Clark would have received in the twenty years following her dismissal.

Clark became a more public supporter of feminism during her retirement. “I think the civil rights movement would never have taken off if some women hadn’t started to speak up,” she told interviewer Cynthia Stokes Brown. She knew that during that era, her own contributions had not always been recognized. In a 1976 interview, she recalled how often Rev. Ralph Abernathy had asked, "why was Septima Clark on the Executive Board of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference? And Dr. King would always say, 'She was the one who proposed this citizenship education which is bringing to us not only money but a lot of people who will register and vote.' And he asked that many times. It was hard for him to see a woman on that executive body.”

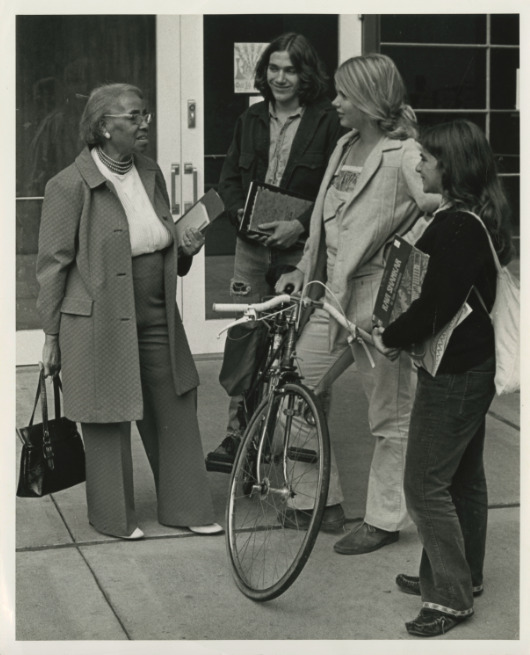

Clark shared her wisdom in lectures on college campuses. “The greatest evil in our country today is not racism but ignorance,” she told Antioch College in 1970, adding, “I believe unconditionally in the ability of people to respond when they are told the truth.” Clark made it clear that to her, “the truth” included the country’s long history of systemic racism. In a 1975 essay, she commented further on this history. “Nothing that is Black and whole and alive in America can be fully comprehended apart from the endless white thrusts toward our exploitation, deracination, death and dismemberment,” she wrote. “Indeed, only then can we fully understand and celebrate the miracle of our continued vibrant living presence. Only then can we properly understand the nature of the dying among us.”

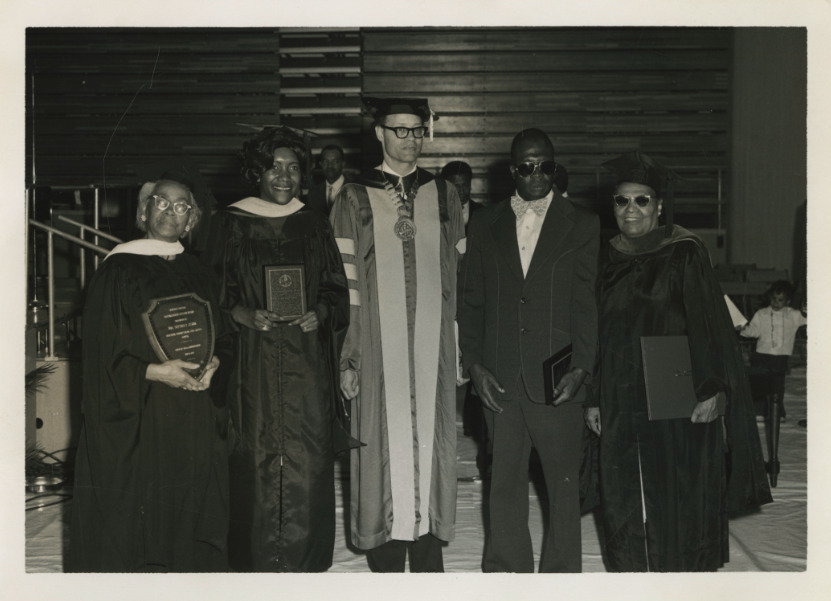

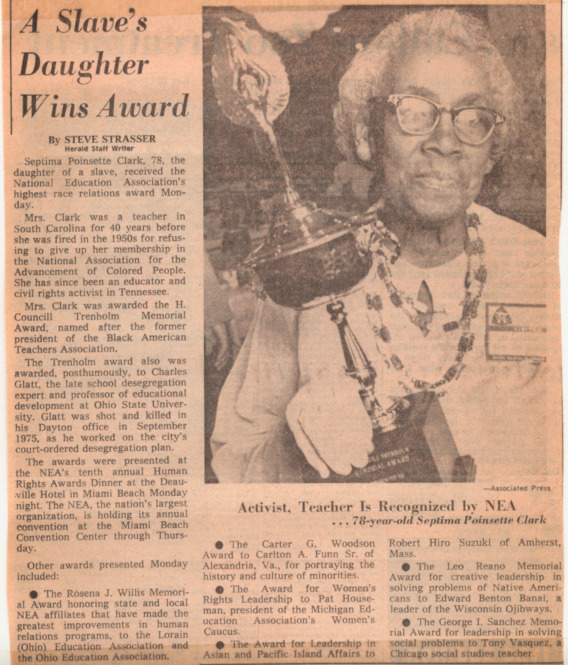

Recognition continued during the 1970s and 80s. Across the country, people sought her out for interviews and lectures. President Jimmy Carter, South Carolina governor Richard Riley, and other national organizations bestowed awards upon Clark, whose activism had once been branded anti-American. “Now it has come to the place that [Charlestonians] see that the work I was doing was really worthwhile,” she told Brown in 1979. “I’m very glad that I had enough patience and enough of the non-violent philosophy within me that I could take it and not be bitter towards any of them. They were afraid, but I wasn’t,” Clark said, adding, “Some people here are still afraid.”

Throughout her career, people had tried to intimidate Clark, but could not make her quit. “I have had a lot of things to happen to me and I had to live through it,” she reflected in 1981. “I’ve had policemen sent to my door looking for the fight. Pure harassment. I’ve had firemen sent to my door looking for the fire. Pure harassment. I’ve had people call and curse me over the telephone, and I would just say, “Thank you, call again.” I’d put the phone down and here would come another call. There were nights when I couldn’t sleep for that kind of thing.” Clark expressed her ongoing resolve and her hope for even more change in the future: “There were times when I felt discouraged, too, but I felt I had to go on. I could not do anything by quitting. A quitter received nothing. . . . I know I’m not going to live to see a black President, but I do hope in times to come there will be one.”

Images