Belonging: College of Charleston Honors Septima Clark, 1978-2020s

Honoring a Visionary

C of C, which once excluded Black citizens, awarded Clark an honorary doctorate in 1978. It now safeguards her papers at the Avery Research Center. Dr. Clark’s life provides lessons for the College and inspiration for all who work for justice and equity.

In the Cistern Yard in 1978, the College of Charleston presented an honorary doctorate to a woman whose father had been enslaved by one of its trustees. "I cannot describe how I felt when they notified me of my nomination to this honor,” Clark told a reporter. “It was like being Cinderella. . . just after she puts on her glass slipper. After all, this is the same college the campus of which I have passed so often, not being allowed to enter it as either a student or a teacher.”

Conferring this honor upon Clark was one of the College’s efforts to undo its past practices of exploiting and excluding African-descended people, practices that dated back to the institution’s beginnings. Wealth derived from enslaved people founded the College, starting with the first bequests the College received in 1770. Historic Randolph Hall was built using enslaved labor. For most of its history, the College had excluded Black citizens from its classrooms. In the 1940s, Avery students, including future State Representative Lucille Whipper, had written the College to request applications, but were told they were not eligible to apply to this public school supported by all taxpayers. In 1949, the city of Charleston sold the College to the Board of Trustees for one dollar so it could become a private school and continue excluding Black students. In the 1950s and 1960s, some students, including Frank Sturcken, protested, but the College did not accept Black students until 1967.

In 1972, to support Black students, President Ted Stern hired Lucille Whipper to work at the College. The first Black faculty member, Owilender Grant, was hired in 1972; the second Black professor hired was Eugene Hunt, an Avery graduate who had previously taught at Burke High School, where he supported students who participated in the Charleston civil rights movement. Professor Hunt developed the College’s first African American studies courses in the 1980s. He also worked, along with Lucille Whipper, to establish the Avery Research Institute for Afro American Culture in 1985. This 1860s building, where Septima Clark had studied and worked in the 1910s, was restored as the Avery Research Center and opened to the public in 1990. Clark’s papers are now housed there.

Clark passed away in 1987. A few months later, the College named the Septima Clark Auditorium in her honor. Despite this institutional recognition, many twenty-first century College of Charleston students were unfamiliar with the legacy of the activist who was born at 105 Wentworth Street, on the College’s campus. Some of the College’s Teaching Fellows, studying Clark in Professor Jon Hale’s Foundations of Education class, were shocked there was no marker at Clark’s birthplace. These students raised funds and submitted paperwork necessary to install a State Historical Marker on the site, where it was unveiled in 2018, on Clark’s 120th birthday. Grandchildren in attendance recalled their years with “Mama Seppie.” Charleston’s Poet Laureate Marcus Amaker read his poem, “Movement’s Mother.”

Charleston’s poinsettia

was a warrior woman

who blossomed

despite an unholy city’s

unsettled winds.

The Avery Research Center has now digitized many of Clark’s papers. Some are featured in an online exhibit on the College’s Lowcountry Digital History Initiative. Philanthropist Linda Ketner created a scholarship named for Clark and Esau and Janie Jenkins in 2022. The College installed a permanent exhibit on Septima Clark’s life in the Septima Clark Auditorium in 2023, linked to this online tour, so that more students would know of Clark’s achievements and their links to the College and surrounding neighborhoods.

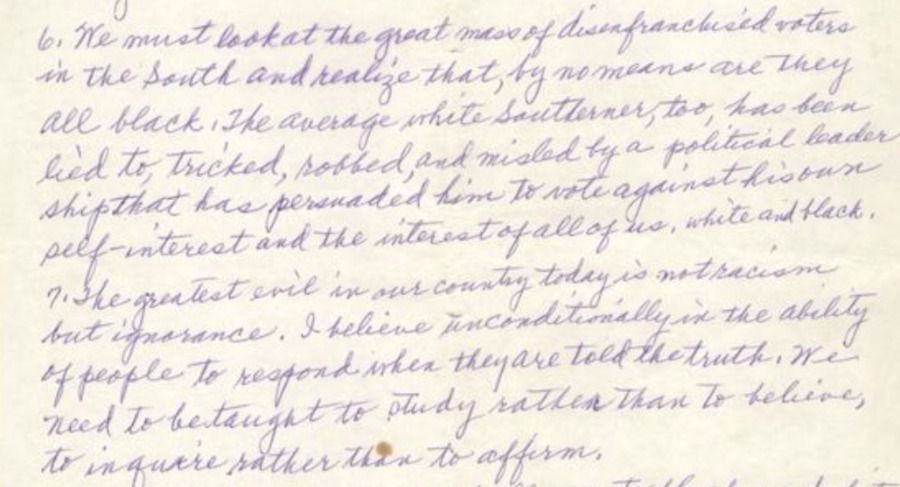

Dr. Clark once wrote, "We need to be taught to study rather than to believe, to inquire rather than to affirm.” In this spirit, the College strives to teach students to think for themselves.

Racism and systemic inequities continue to damage American society, a century after Clark’s activism began. In 2015, a young white supremacist massacred nine members of the Emanuel AME church, steps from the site of Clark’s old Henrietta Street home. In the wake of the massacre, Google commissioned a 2016 study by the Avery, which documented significant disparities between Black and white residents’ income, health, education, and housing.

In May 2020, after George Floyd and other Black citizens were murdered by law enforcement, protestors in Charleston and the nation took to the streets, calling for Black lives to be valued. Septima Clark would have supported these protests and other efforts to make American society more equitable. "I just tried to create a little chaos,” she said of her activism. “Chaos is a good thing. God created the whole world out of it. Change is what comes of it."

Change can be chaotic and frightening. It can disrupt habits and traditions that seem unchangeable. But visionaries like Clark can inspire us to overcome our fears and our complacency. If we continue to study and inquire, as Septima Poinsette Clark did before us, we too can find ways to transform and heal a troubled world.

Images