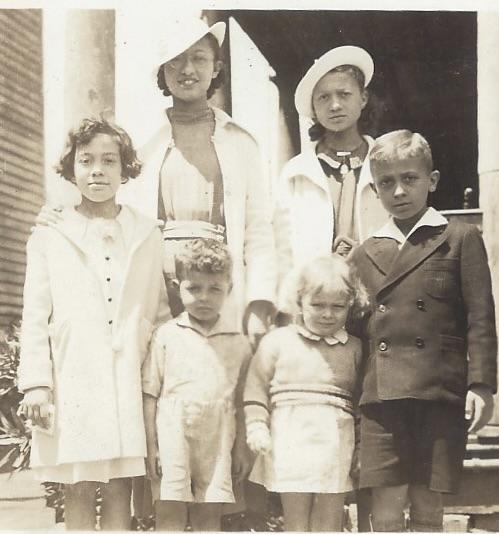

In 1925 a young entrepreneurial couple, Edward Leon Guenveur Sr. and Lauretta Goodall-Guenveur, purchased a home on Coming Street in the midst of a thriving African American community, adjacent to the College of Charleston. The living descendants recall how the five siblings had to walk around the perimeter of the College to get to the grocer, instead of simply cutting directly through the campus. The Guenveurs raised their five children in the home and established a successful plumbing company, which, in 1964, was believed to be the oldest plumbing contracting company in the city. The home remained in the family for nearly eight decades before it was purchased by the College of Charleston in 2006.

Originally constructed in 1772, then reconstructed in 1884 by John H. Kornahrens as a two-story Charleston Single House using its original timber, 57 Coming Street tells the story of a once thriving African American community. This dwelling was home to the Guenveur family for nearly eight decades before being acquired by the College of Charleston. Descended from free people of color in Charleston, the Guenveurs were a middle class family that were a part of robust and integrated Harleston Village, a south of Calhoun Street neighborhood. Harleston Village stretched from King Street on the east to the Ashley River and Broad Street to the south.

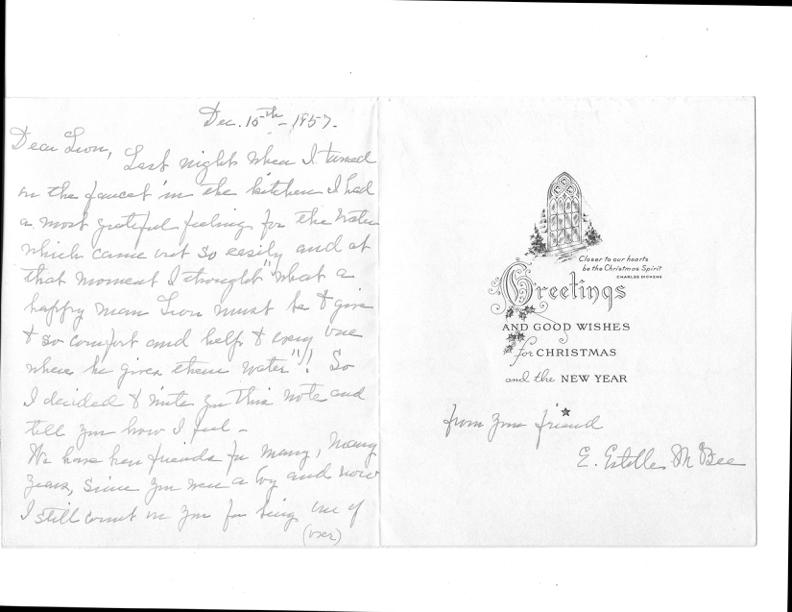

Edward Leon Guenveur Sr. was born in Charleston’s 3rd Ward (Vanderhorst Street) in 1892 to Joseph Paul Guenveur and Eugenia Florence Whiting. Joseph made a living as a carpenter and served as the superintendent of St. Peter’s Sunday School. He was also a state representative of the Colored Catholic Congress, which was a national organization. Affectionately referred to as Leon, he trained as an apprentice for ten years before earning the designation of Master Plumber. He started an independent plumbing company with his wife Lauretta serving as office manager thereafter. The business they operated at 57 Coming was responsible for installing indoor plumbing in many of the peninsula’s communities as new standards and technologies became available. Leon shared an enduring friendship with master blacksmith, Phillip Simmons. This is partly evidenced in the two wrought iron gates at the 57 Coming property. The main entrance to the home exhibits the more obvious gate, but a second smaller ironwork gate graces the lowest level of the home. Evidence from the Guenveur receipt books also suggests that Leon consistently worked with Thomas Pinckney, known for his preservation work throughout Charleston. Pinckney was specifically responsible for the restoration (1929) of the piazza entrance, the grated fireplaces with wooden mantels, and the exquisite front stairwell of the home.

Lauretta Goodall was born in 1894 to Emma Bell Goodall and Lindsey Baxter Goodall, clergyman of the Baptist church. Emma, like others in her family, learned to be a seamstress. Her mother, Maria Bell, was a laundress, then merchant and landlord. She acquired the properties at 27 and 29 St. Phillips Street in 1872. In the 1910 census, Emma is listed as a widow living with her two children (Lauretta and Baxter) at 27 St. Philip Street. The properties were held by the Goodall-Guenveur family for almost a century. The College of Charleston purchased and demolished the homes and the lot is now the present location of the Thaddeus J. Street Education Center (25 St. Philip Street). Lauretta and Leon were part of an intergenerational African American community. They both attended and graduated from the Avery Normal Institute, Lauretta in 1915 and Leon in 1911. The Avery Normal Institute was the first secondary school for African Americans established in Charleston. Lauretta trained as an educator while attending Avery and learned dressmaking and fine handwork at Essie Boston’s Fine Dress Shop. She offered private dressmaking services until she married in 1920.

The Guenveur children (Florence Louise, Helen Marie, Anna Mae, Edward Jr., and Loretta Ruth) attended Immaculate Conception (200 Coming Street) for grammar and high school, where the Oblate Sisters of Providence, the first successful Roman Catholic sisterhood in the world established by women of African descent, offered an exceptional education. The family attended St. Peter’s Catholic Church until it was shut down and the black parishes consolidated in 1967. Memorial bricks honor their departed family members at St. Patrick’s Catholic Church on 134 St. Philip Street, which housed a white congregation before then. The children had access to the library collection, enrolled in music lessons, and played sports at nearby Dart Hall Branch Library (19 Kraacke Street). In 2001, Florence recalled the Harleston Village of her youth. The family shopped at Tecklenburg’s Grocer on the corner of St. Phillip and Wentworth Streets and were neighbors to families that are still recognizable in Charleston: Sotilles, Steinbergs, Lawtons, and Bullards. She recalls Mr. Horry, a butcher on Spring Street and the Daniels, who were related to the founder of Jenkins’ Orphanage.

Within an eight-block radius, African Americans in the Harleston neighborhood also could go to school, attend church, find haircare, entertainment, and shop. The segregated Lincoln Theatre was a brisk walk away at 601 King Street. Despite being barred from other stores and shops, African Americans were allowed to shop at Condon’s, Furchgott’s and Kerrison’s, stores also located on King Street. The Beauty Box and Buchanan Barber College, both established by Laura Mack Buchanan Sims, were nearby at 87 and 89 Coming Street, and the Brown Fellowship Cemetery, where many buried and visited their dead, was at 52 Pitt Street. These properties are among the Harleston Village real estate acquired by the College over the last half century.

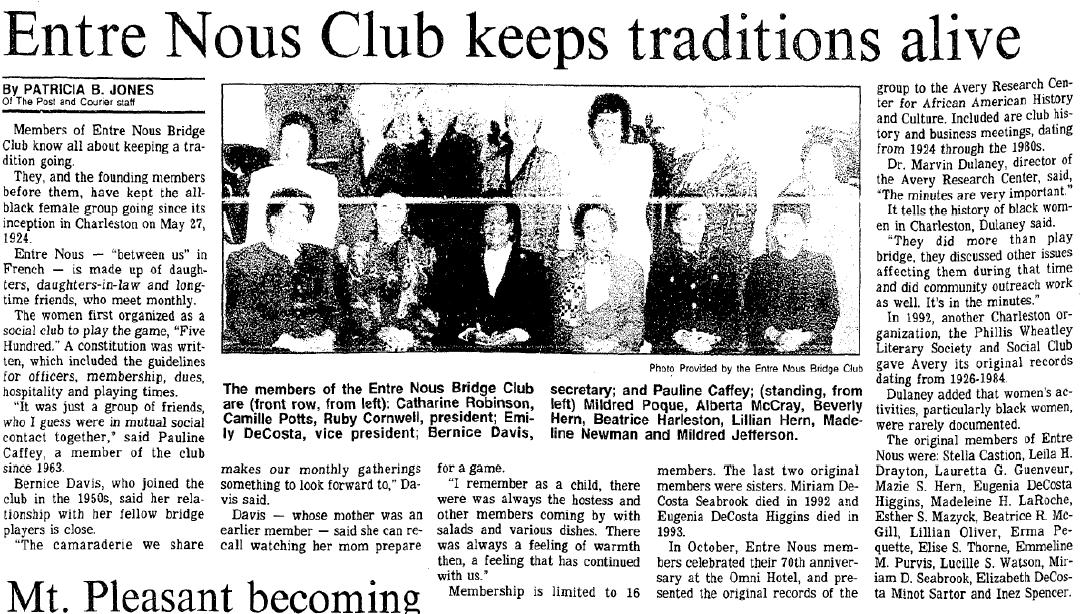

As a master plumber, Leon provided an essential service for his neighbors and the City of Charleston. Testimony from his daughter, Dr. Florence Louise Guenveur Streat, suggests that he and his wife provided services for payment in kind for elderly clients and religious institutions. The family, in fact, was dedicated to improving the entire community through service and education. Leon founded the Owls’ Whist Club, a fraternal organization for African American businessmen, in 1914, with his brother, Joseph Paul Guenveur Jr and 14 friends. Lauretta was a founding member of the Entre Nous Bridge Club, in 1924. While they had college aspirations for their five children, none of them could attend the College of Charleston or even walk through the campus until it was integrated in 1967.

The living descendants recall how the five siblings had to walk around the perimeter of the College to get to the grocer, instead of simply cutting directly through the campus. Despite the Jim Crow segregation of the time, the Guenveur family drew inspiration from their proximity to the expanding College of Charleston. Leon and Lauretta valued education and cultivated this love for learning in their children. The siblings attained post-secondary educations at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and went on to excel in their professional lives.

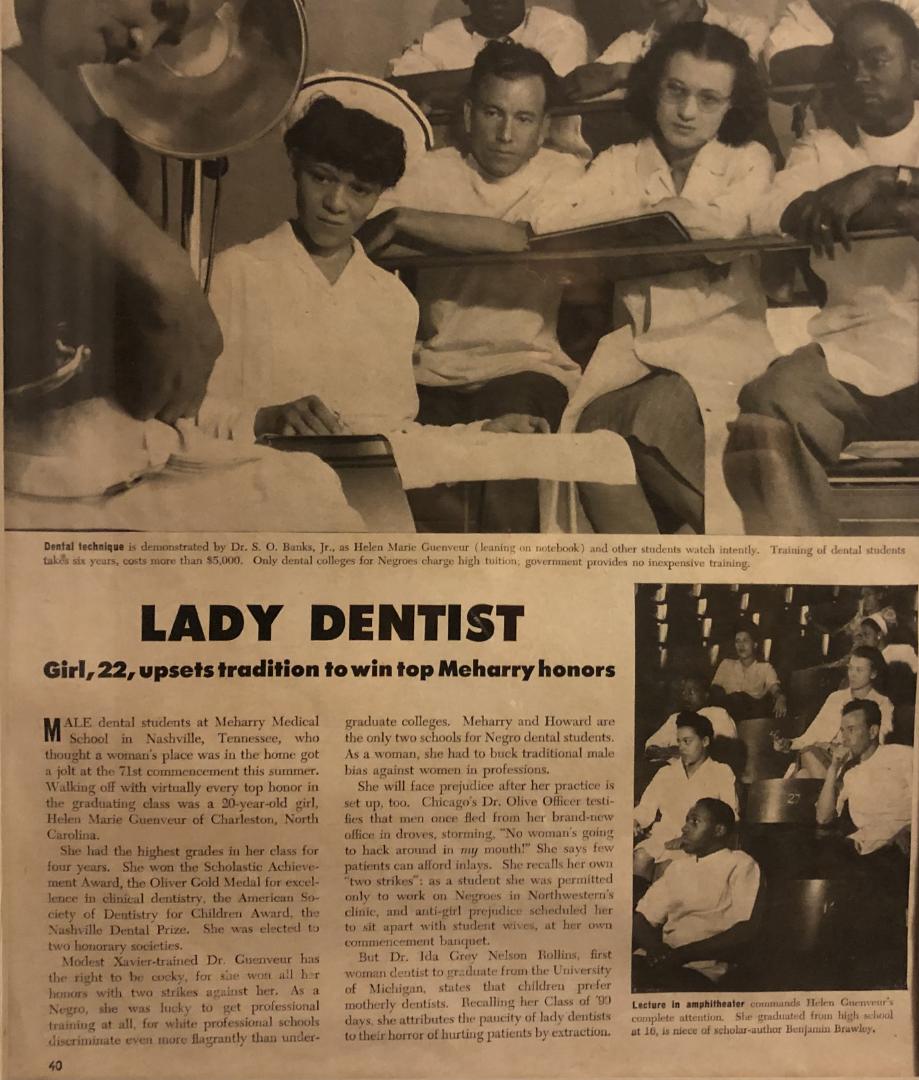

Dr. Helen Guenveur Smith was a pioneering dentist and community activist. In 1954, she married Attorney Sherman W. Smith Sr. After moving to Los Angeles, the couple built the historic Palm Vue Motel, where "people of all races are welcome." In Berkeley, she started her 50 years of private dental practice. She was a founder of the Watts Health Foundation, providing dental services there for two decades. Her husband served on the Superior Court bench in California.

Dr. Florence Louise Streat, a philanthropist and professor at Bennett College, was named the United Negro College Fund’s Outstanding Faculty in 1984. She married William Streat Jr., a Tuskegee Airman officer who became the second minority person registered to practice architecture in North Carolina. He served as Professor and Chairman of the Architectural Engineering Department at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University from 1949 until his retirement in 1985. The Streats met in Greensboro and were married in 1950 in the front parlor of 57 Coming. After her father passed away in 1969, Dr. Streat and her husband cared for the house. Mr. Streat was instrumental in the historic preservation of the home winning, in 1973, a Carolopolis Award from the Preservation Society of Charleston. Dr. Street was also instrumental in the preservation of St. John Cemetery.

Mrs. Anna Mae Guenveur Newman and Mrs. Loretta Ruth Mikell both graduated from Bennett College and had long careers as elementary school teachers in southern California. Loretta Ruth married Rollins J. Mikell Jr. The two were classmates through their entire matriculation at Immaculate Conception. He became a Computer Systems Specialist with a degree in Mathematics from North Carolina A&T. Edward Leon Guenveur Jr. served in the US Army during the Korean War and, like his father before him, became a successful businessman. All the children left Charleston to pursue their careers and raise families elsewhere, but returned regularly. Ten grandchildren, all born and raised in California, have contributed to their communities in education, as independent businesspeople, in the healthcare professions, and in the creative arts. Despite the geographical distance between Charleston and California, the generations have always been steeped in 57 Coming Street lore.

Helen’s children, Louise Angele Smith and Roger Guenveur Smith, have been particularly active in recognizing and upholding the family’s impactful and pioneering history in Charleston and maintain strong ties to the College of Charleston. Mr. Smith, an Obie-winning actor, director, writer, and frequent collaborator with Spike Lee, holds an undergraduate degree in American Studies and attended the Yale School of Drama. In addition to sustaining ties to his ancestral home, he has brought his passion for history and the stage to the College by leading a Performing History Workshop for students in the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture in 2011. Almost exactly a century before, Lauretta and Leon had earned their diplomas from the Avery Normal Institute.

In 2000 the Guenveur siblings endowed a scholarship at the College of Charleston in memory of their parents and the value they placed on work ethics and education. In 2001, Louise Guenveur Streat and Roger Guenveur Smith each received an honorary doctorate of humane letters from the College. Roger gave the commencement speech at the Graduate School ceremony that year. Notwithstanding being barred from admission to the College based on race, the Guenveurs modeled the behavior they believed in—sharing one’s resources and encouraging excellence in one’s community. The Edward Leon Guenveur Sr. and Lauretta Goodall-Guenveur Endowed Memorial Scholarship is awarded to a College of Charleston senior, from Charleston County, who maintains the highest academic average during the first three years of matriculation.

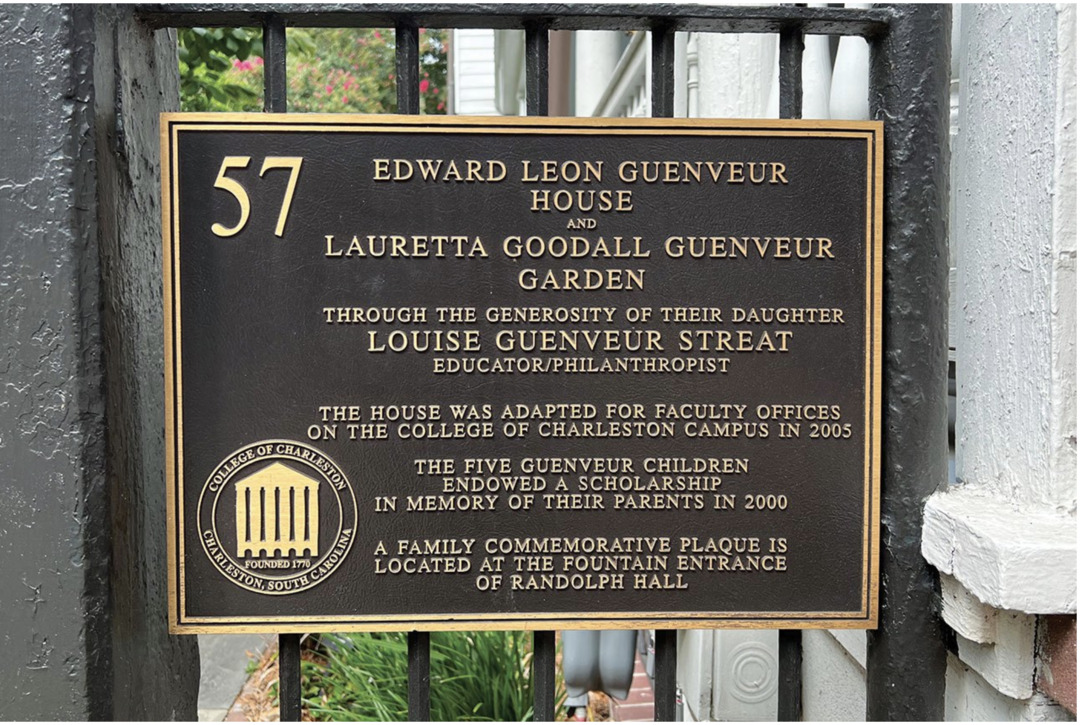

The College of Charleston Foundation acquired the property in 2004 through a sale from the family. Dr. Streat generously supported the adaptation of the family home for faculty use. The Foundation subsequently sold the property to the College. The site was dedicated as the Edward Leon Guenveur House and Lauretta Goodall Guenveur Garden on April 28, 2006. It currently houses the Department of Psychology. Inside the historic house are displayed books read by the family, family photographs, and even one of Mr. Guenveur’s plumbing tools which is symbolic of the family’s philosophy.

Louise Smith and Roger Guenveur Smith, the children of Dr. Helen Guenveur Smith, are committed to the upkeep of their family legacy and work directly with the College to preserve the history of the neighborhood they knew as their ancestral homeplace. Louise and Roger visit Charleston occasionally, dropping by the family home for nostalgic reflection and renewal. Some of the memorabilia from the family home is archived at the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture. The home and garden serve as a sanctuary for faculty, staff, and students. The history of the home and of the Guenveur family is a vital reminder that African American history and culture are integral to the College’s story.

Images