Jones Hotel, 71 Broad Street

The Jones Hotel illustrates the complexities of slavery in the city of Charleston and reveals much about elite Black Charlestonians during the Antebellum era.

The Jones Hotel illustrates the complexities of slavery in the city of Charleston and reveals much about elite Black Charlestonians during the Antebellum era. In Charleston, larger communities of free Black Charlestonians divided along economic and class lines as African Americans attempted to ward off white oppression in a variety of ways. Some formed small groups that defined their status through exclusion, seeking social advancement through economic wealth; others turned to religion for identity, liberation, and guidance.

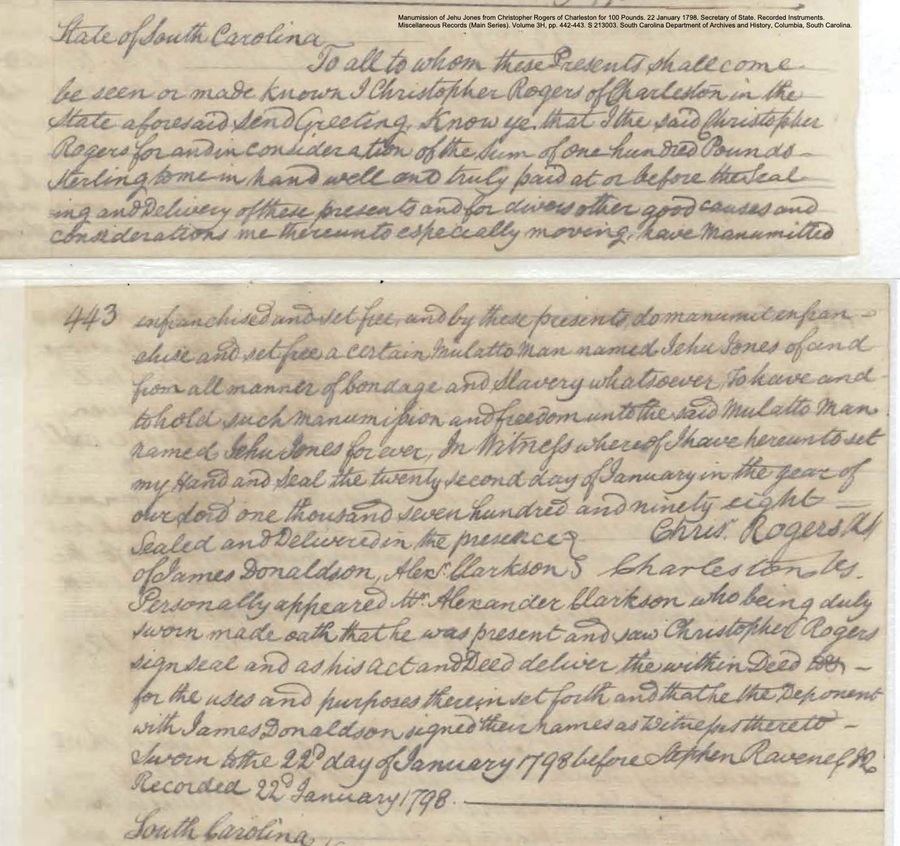

Some of these complexities are revealed by the story of the Jones Hotel and the hotel’s owner, Jehu Jones. Born into slavery in 1769, Jones was enslaved by Christopher Rogers, a successful tailor. Growing up, Jones learned about the skills of tailoring and running a business from Rogers while developing his own knowledge through personal experience.

Because he lived in Charleston, a thriving urban center, Jones was able to utilize and capitalize upon urban modifications of slavery. Although not much is known about Jones’s younger years, it is likely that he took advantage of the “hiring out” system that typically characterized urban iterations of slavery. This system involved an enslaved person, an enslaver, a hirer, and a contract that specified pay, length of labor, and any other stipulations. Enslavers used the hiring out system because they usually took some, if not all, the pay earned by enslaved people. Hirers saw an opportunity to take advantage of enslaved labor without making the costly investment of purchasing enslaved workers. At the same time, enslaved people exploited the hiring out system to gain and increase autonomy and agency over their lives.

In Charleston, enslaved people were hired out to perform various forms of labor, including municipal jobs, domestic work, and—in Jones’s case—tailoring services. While the details of Jones’s involvement with the hiring out system are not known, the historic record reveals that Jones purchased his freedom in 1798 for $140, most likely with money he earned by using the hiring out system. Jones then established his own tailoring shop and enjoyed great economic success. By the early 1800s, Jones not only expanded his tailoring business but also delved into real estate ventures, purchasing property downtown and on Sullivan’s Island in 1802.

Jones’s real estate investments and expanding tailoring business proved very successful. Jones himself gained enough wealth and prestige to join the Brown Fellowship Society, one of the oldest benevolent societies for African Americans in South Carolina. The Brown Fellowship Society was founded in 1790 by Black and mulatto members of St. Philips Episcopal Church who were restricted from using the church’s all white graveyard. The Brown Fellowship Society began as a way to support African American members, and their widows and children, but came to represent classism and elitism among African Americans in Charleston. Usually, only lighter-skinned free African Americans were allowed to join the Brown Fellowship Society. All members had to be relatively wealthy as initiation fees were $50 in addition to annual membership dues. In fact, some members of the Brown Fellowship Society—including Jehu Jones—were wealthy enough to purchase enslaved people. At the end of the Antebellum era in Charleston, 131 free African Americans enslaved a total of 338 people. This fact, combined with the elite Black community’s attempts to separate themselves from enslaved communities, created an environment of tension among Black Charlestonians.

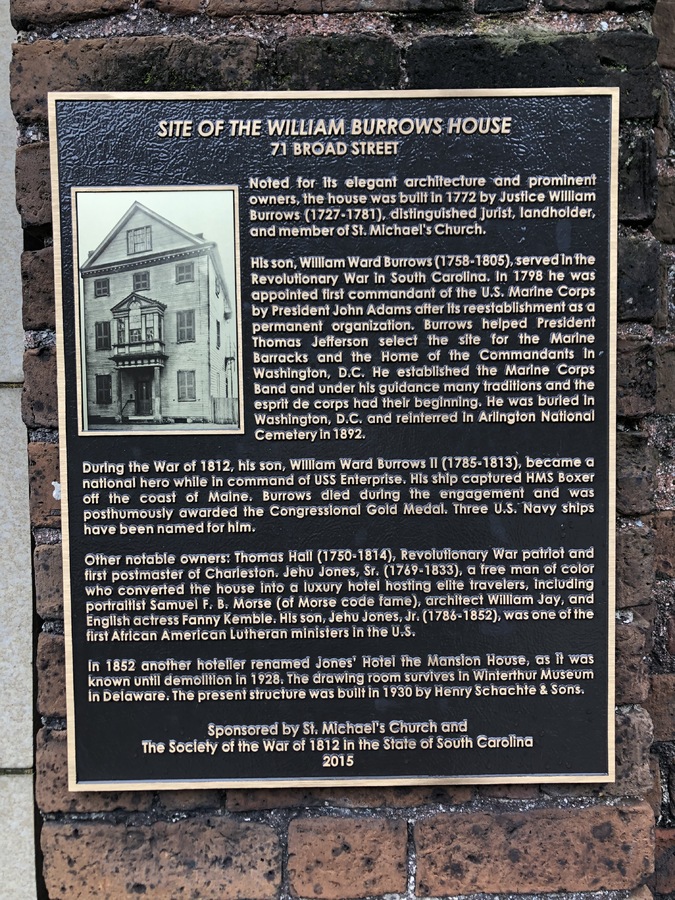

Jones continued to amass wealth and, in the 1810s, made another series of real estate transactions. In 1815, Jones purchased a house and land on Broad Street. The following year, he purchased the Burrows-Hall House (33 Broad Street), turning the building into an inn. Jones and his wife Abagail opened the Jones Hotel in 1816 and catered to elite whites only, using enslaved labor to create an exclusive and luxurious inn. As Jones invested more in innkeeping, he sold the first property to a nearby church. Jones also moved away from tailoring and tasked his son, Jehu Jones, Jr., with running the family business.

The events following the Denmark Vesey conspiracy of 1822 affected the Jones family. Free African Americans—whether they were part of the elite Black society or not—were closely scrutinized and subjected to stricter regulations. Adult African American men were supposed to be supervised by a white guardian. Free Black South Carolinians were not allowed to travel out of the state (and were barred from returning to the state if they traveled after the conspiracy) unless they sought express permission from the state government. Abagail Jones was traveling with her children and grandchildren in New York before 1822 and faced difficulty returning home, ultimately passing away in New York.

Jehu Jones, Sr. passed away in 1833. His estate, which included enslaved people but not Jones’s real estate properties, was valued at $40,000 and was split between his three sons and his stepdaughter, Ann Deas, who had been traveling with Abigail Jones in the 1820s. Deas petitioned South Carolina’s governor for a pardon and returned to Charleston. Deas and Eliza Johnson—another free Black Charlestonian—purchased the Jones Hotel in 1834 and operated the inn until 1847. During that time, Deas continued to use enslaved labor at the Jones Hotel for cooking extravagant cuisine, waiting on the inn’s white clientele, and cleaning and maintaining the establishment.

Financial struggles in the 1840s forced Deas to sell the establishment to a free African American couple, John Lee and Eliza Seymour Lee. They opened Lee’s Boarding House, continuing the property’s use as an inn and site of fine cuisine. The building that once housed the Jones Hotel was taken down in the 1920s (with one room rebuilt in the Winterthur Museum), but the story of the inn and its owners reveals the complexities of Charleston society for African Americans.

Images