63 ½ Coming Street/Solar Pavilion

The complex evolution of a landscape occupied by enslaved and free African Americans

The simple address used to identify this historical site on campus reflects a complex and nuanced history that threads its way through the fabric of American society today.

The simple address used to identify this historical site on campus reflects a complex and nuanced history that threads its way through the fabric of American society today.

Prehistoric peoples traversed this marshy landscape adjacent to what they knew as the Kiawah River for thousands of years. Over time, the Charleston area has been the traditional land of the Etiwan, Kiawah, Santee, Edisto Natchez-Kusso, and Wassamassaw people. This site was and still is part of higher ground where humans have long-sought to build away from tides and floods. The British Army selected an area close by to build a large brick barracks (1758-59) to house a garrison of 3,000 soldiers leading up to the American Revolution. A portion of this barracks later served as the core building of the first College of Charleston campus.

It was also during the mid-eighteenth century that the 162-acre section of Charleston in which this site was situated was laid out and named Harleston Village. Affra Harleston Coming was one of the first female settlers. Some nearby structures predate the American Revolution and were part of this early suburban development effort. It should be noted that the chain of title for this area is tangled and made more complex by changes in house numbers over time along both Bull and Coming Streets.

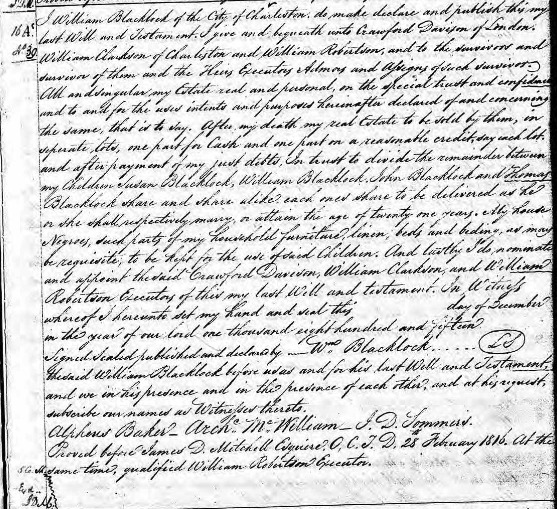

The William Blacklock House at 18 Bull Street was constructed around 1800 on Lot 122 indicated in the 1770 Rigby Naylor Plat of Harleston Village. William Blacklock enslaved 40 individuals according to his estate records from 1816. Edward Lightwood owned the two lots of land that comprised the corner of Bull Street and Coming Street (119-120) and upon his passing in 1799, William Blacklock acquired these as well.

It was Katherine Blacklock and her husband Nathaniel Farr who first developed Lots 119 and 120 after inheriting the land from her father. They had built a home here at what is today known as 69 Coming Street or the Farr House by 1817. Both Katherine and Nathaniel passed away by 1824 and the entirety of these lots, including the Blacklock Home, were offered at auction.

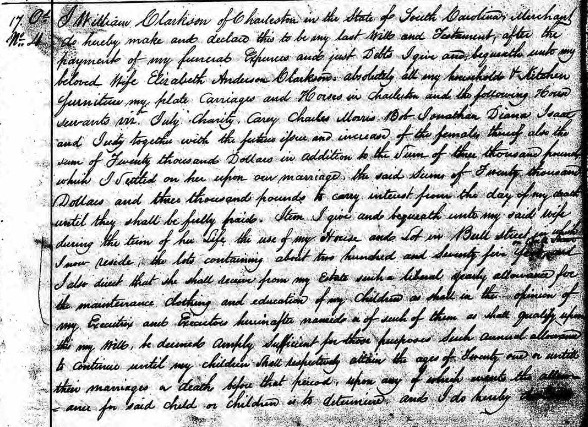

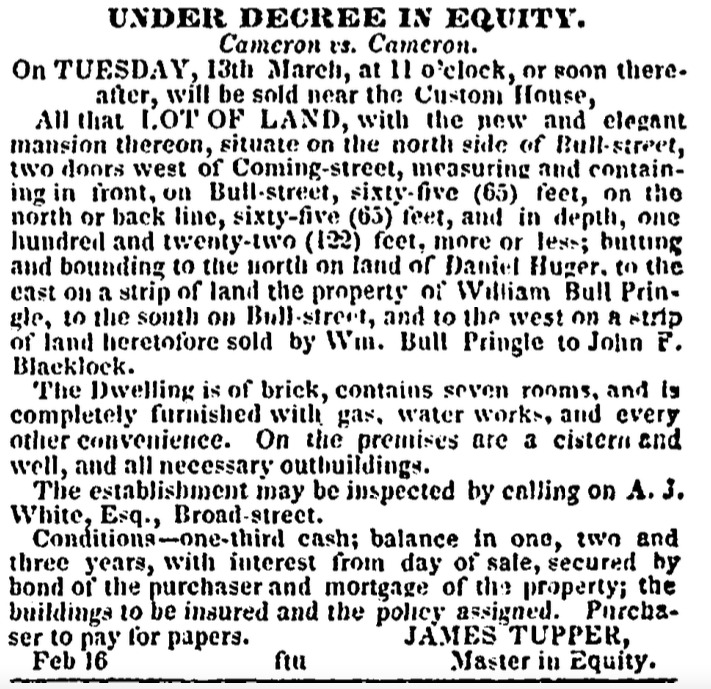

William and Elizabeth Clarkson thus acquired all the properties and the buildings therein in 1824. William died in 1825, leaving the properties to a trust that would support Elizabeth and the couple's children. Included in his will are the “house servants,” July, Charity, Carey, Charles, Morris, Bob, Jonathan, Diana, Isaac and Judy. These are the individuals that helped to build and maintain the domestic environment that was enjoyed by their enslavers in this corner of Harleston’s Green as it was known then. By 1848, William Bull Pringle had purchased the properties that were once Lots 122 and 119 with Elizabeth Clarkson’s passing during the next year. Daniel Huger had purchased 69 Coming Street also in 1848. According to the 1850 Federal Census Slave Schedule, Daniel Huger had enslaved nine male and female persons at this property.

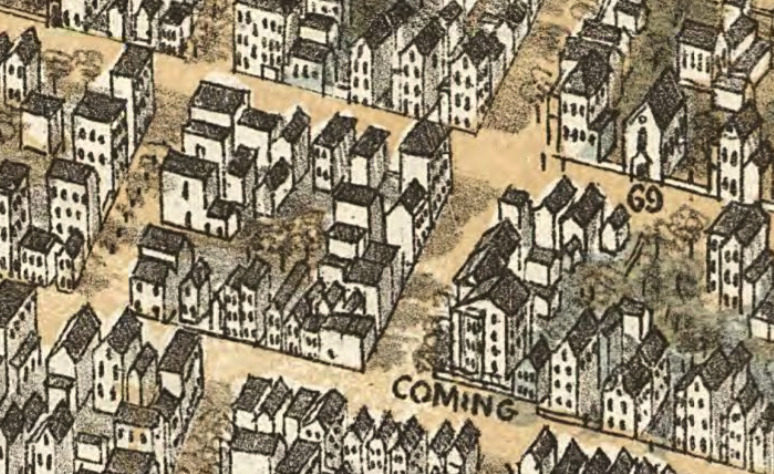

No additional structures outside of 18 Bull and 69 Coming Streets are found in this area through 1852 when the Bridgens and Allen map was published. A plat surveyed in 1849 by the famous Charleston architect, Edward Brickell (E.B.) White, indicates that what would become 12 Bull Street was also sold to him that year by a cousin, William Bull Pringle, who was then the owner of 18 Bull Street. E. B. White enslaved three older female individuals during this period while he was serving as a member of the College of Charleston's Board of Trustees.

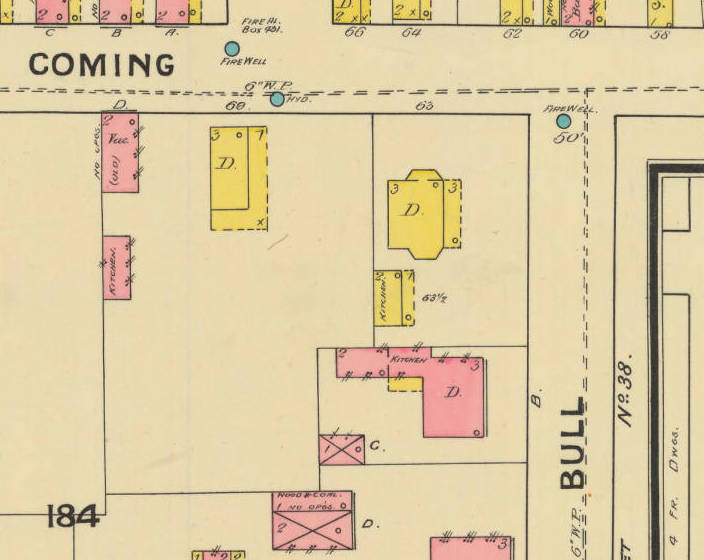

By February 1855, an advertisement in the Charleston Mercury indicates that a home had been built at 12 Bull Street and the land to the east was still owned by William Bull Pringle. This advertisement is the first indication that a building was now apparently located at the corner of Coming and Bull at this time as it mentions that 12 Bull Street is “two doors west of Coming.” The Kitchen and Dwelling we are calling 63 ½ Coming Street may be this first door. The building that the College of Charleston excavated likely served as a kitchen for 69 Coming Street (further up Coming Street) for several years.

The 69 Coming property, once owned by Daniel Huger, became part of a multigenerational path to greater wealth. Robert Dewer Bacot had married Huger’s daughter Julia in 1843. By the 1850s, Bacot was involved in fire insurance in Charleston, and according to the 1859 City Directory, resided at 69 Coming Street. Bacot had advanced from a clerk position to a “planter” by using enslaved labor on cotton and rice plantations that he and his family operated outside of Charleston. The 1861 City Census has a new address, 61 Coming Street, which is the first indication of a structure with a specific address located on the corner of Bull and Coming Streets. This is likely the structure indicated on the 1888 Sanborn maps as 63 Coming Street with a “Kitchen” at the rear. Robert Dewar Bacot, his extended family and a range of enslaved people, servants and renters would occupy this space for the next half century. It is this period of time that was the primary subject of archaeological work conducted by faculty and students from the College of Charleston's Archaeology Program in 2021.

Like much of the area currently occupied by the College, the neighborhood surrounding the site was diverse in many ways. Black Charlestonians resided and worked here, owned property, worshipped, and maintained burial grounds.

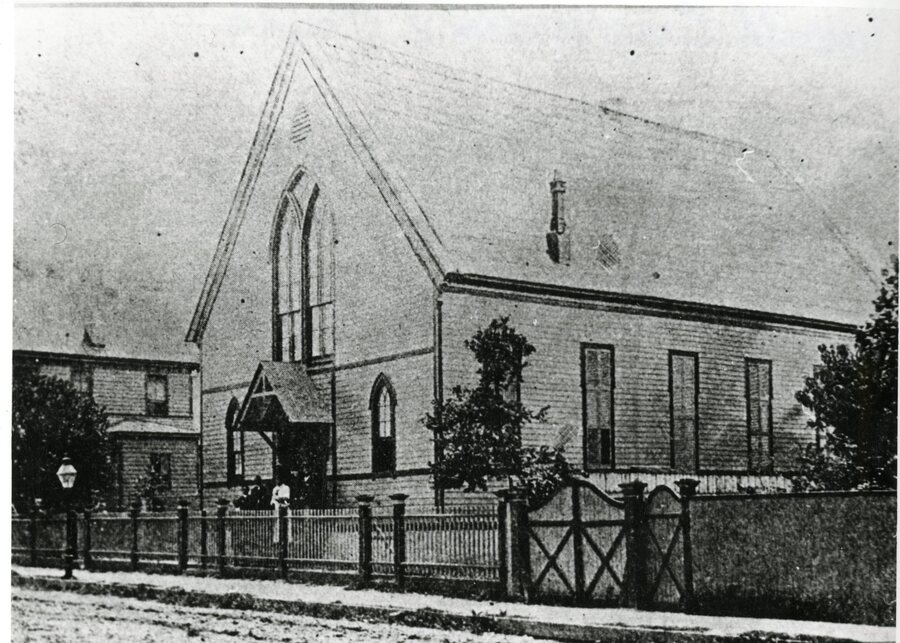

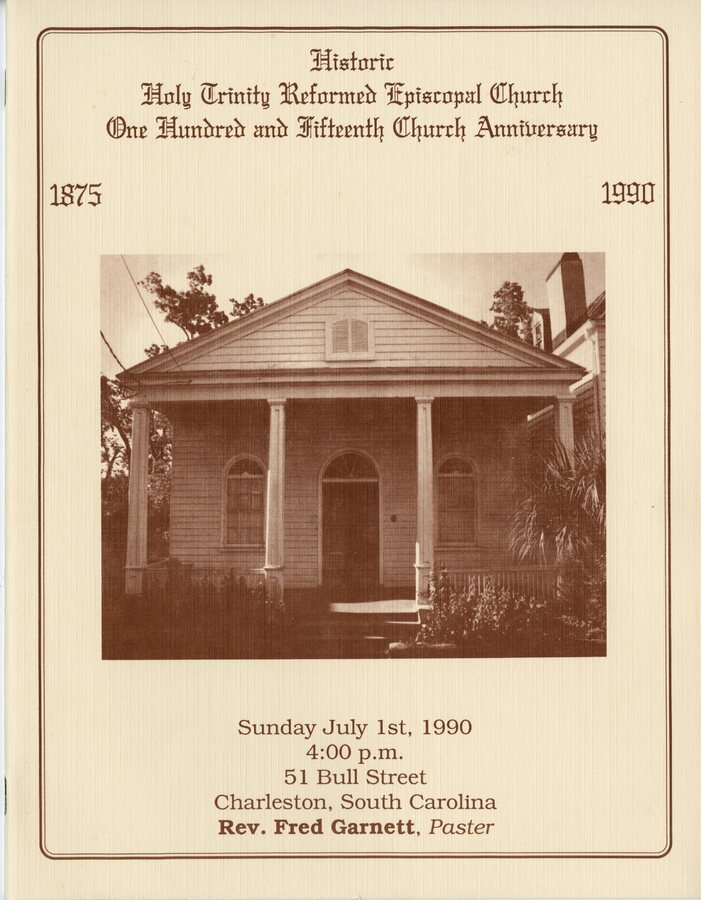

By the 1880s several Black churches were very close to the site, including Holy Trinity Reformed church on 51 Bull Street, Old Plymouth Congregational Church at 41-43 Pitt Street, and Mt. Zion AME Church at 5 Glebe Street.

In Spring 2021, faculty and students from the college's Archaeology Program executed a Phase III data recovery (a full archaeological excavation) on the College of Charleston campus in preparation for the installation of a solar pavilion, supported by the United States Department of Energy by way of the South Carolina Energy Office. Recovered artifacts date as far back as the 1720s while the oldest architectural remains date to the mid-nineteenth century. These artifacts are directly tied to the African American experience in Charleston and reflect the condition of their lives and their forced labor in a landscape where agency was inhibited but never fully crushed.

Initial examination of the artifacts indicated a diet that included large quantities of oysters, chicken and less expensive cuts of pork and cow. Ceramics found here are likely hand-me-downs from enslavers and later employers.

The building did not only serve as a space for foodways. The documentary record indicates that various Bacot family members had offices at both 69 and 63 Coming Streets. Records indicate that by the early 1880s, two African Americans resided at 63 ½ Coming Street. William Lambert was a “laborer” while Paul Samson was a “driver.” It may be that they both were once enslaved by the Bacot family. One artifact is particularly evocative.

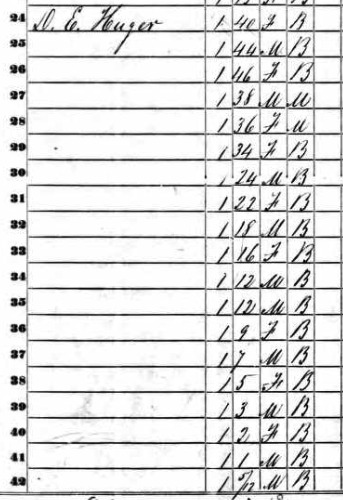

Slave tags were made in Charleston from the 1700s until 1865. They were issued to enslaved persons giving them agency to move within an economic and social landscape fraught with danger and restrictions. Specific occupations were stamped on the tags. Tag number 731 is dated 1853 and has been x-rayed and the occupation stamped on this tag is “SERVANT” or someone occupied in the domestic realm. It was found adjacent to the hearth from the kitchen building at 63 Coming Street. It may indicate that once the home was completed in the early 1850s that meals were prepared by a hired enslaved person or that the Bacot family hired this individual out. The original City of Charleston ledger books recording the names of the enslaved and their enslavers were likely destroyed when the Orphan House on Calhoun Street was torn down in the 1950s to make way for a Sears & Roebuck. In time, other documentary evidence may enable us to learn the name of the individual that carried this heavy burden.

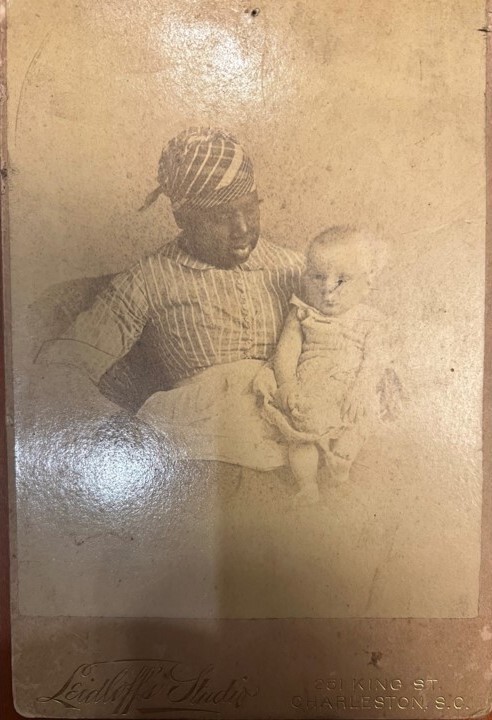

Documentary and archaeological evidence compels us to understand this space and place in a variety of lights. It was a slave quarter. It was a kitchen that served the enslaved and the family that enslaved them. It was also rental property and a business address. We now have names for some and the artifactual evidence that tells something of the daily life that transpired here. In the Bacot Family Papers Collection at the South Carolina Historical Society, there is an evocative image taken on June 3, 1889, of a nanny holding Daniel Huger Bacot, Jr. This anonymous caretaker may be one of two women listed in the 1880 census: Mary Moore, age 38, was a “servant’” and Jane Bell, age 32, was a “washwoman.” On the photograph, as so often is the case, the person in power (an infant) is named, but the Black woman caring for the infant is not. Since the majority of the 1890 census was destroyed by fire, her name cannot be found in that record, but in the future, in seeking to learn her name, the Bacot Family papers at the University of North Carolina could yield helpful insight.

In summary, the data reflect a complex evolution of a landscape occupied by enslaved and free African Americans. 3D-modelling of stratigraphy and architectural elements along with faunal and artefact analysis has informed a robust (re)interpretive plan that will impact visitors, students, campus employees and the City for many years to come. This joint effort by faculty, students and staff has contributed to a campus-wide cultural heritage management plan that includes the most antebellum structures of any American university and the unvarnished truths that lie beneath our feet.

Images