Black Burial Sites and Memorials on Rivers Green

Commemorating Black Charlestonians on C of C's campus

Over two centuries ago, free people of color buried their dead near this spot. In 2008, the College installed this memorial on Rivers Green, outside Addlestone Library. Nearby, another marker commemorates a beloved librarian and member of Emanuel AME church.

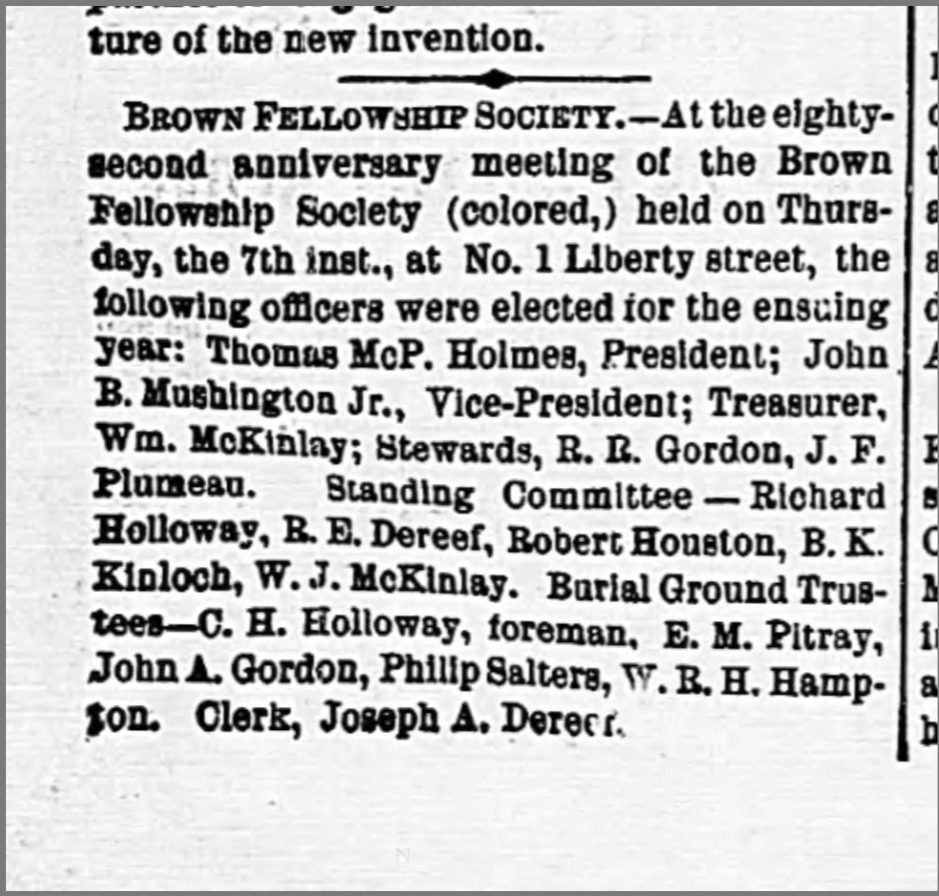

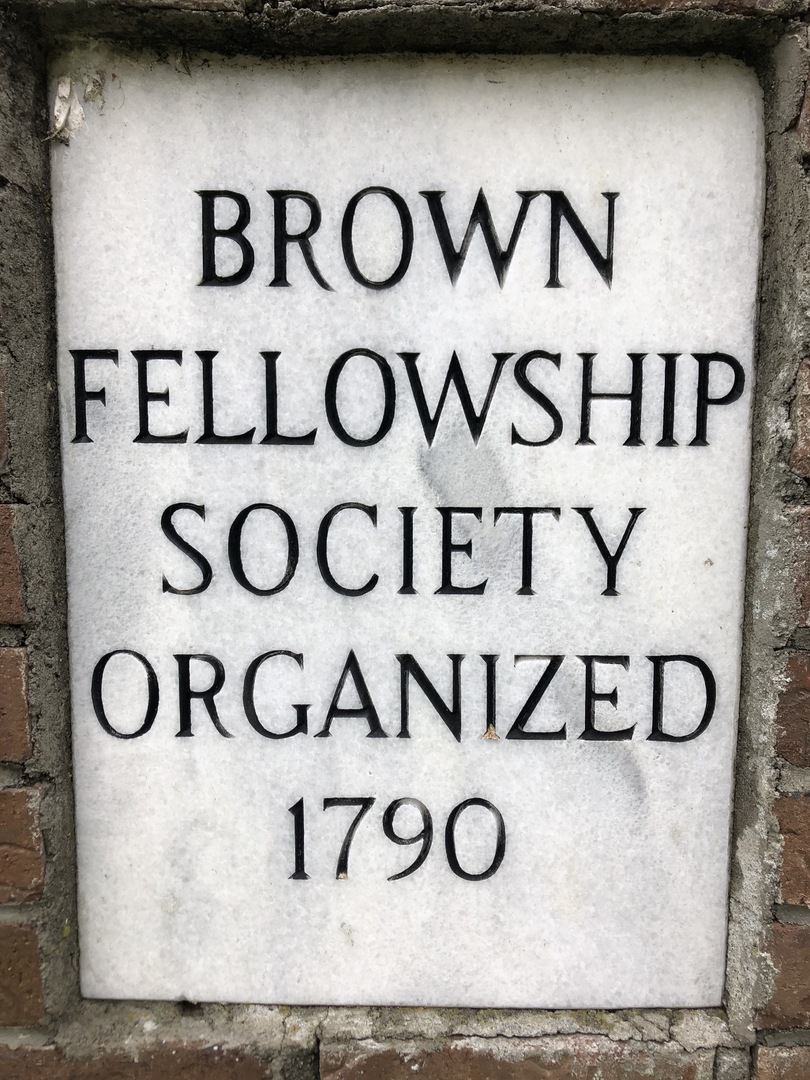

The Brown Fellowship Society, founded November 1st, 1790 by Charleston’s community of elite free persons of color, is more than two centuries old. This Society was once central to the African American community of Charleston, and members maintained a cemetery next to their meeting hall on Pitt Street. This property is now a paved parking lot for Addlestone Library and Rivers Green. Every single day students and staff at the College pass through one of the most important sites in the history of the City’s African American community, whether they know it or not.

In 1790 five members of Charleston’s free Black elite - James Mitchell, George Bampfield, William Cattel, George Bedon, and Samuel Saltus - gathered together and formed the Brown Fellowship Society. The society was meant to be a mutual aid association for the free Black community in a time that permitted them minimal benefits from public services. Rather, they had to provide for their own needs even though they were deeply disadvantaged in comparison to their white counterparts.

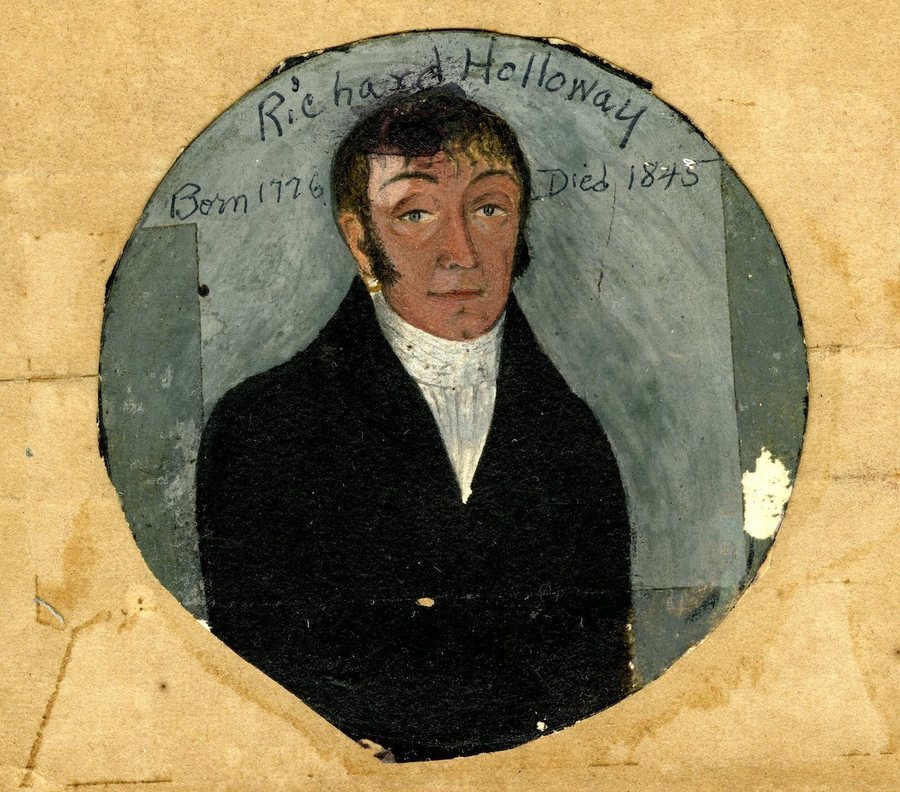

Membership in the Society was originally limited to fifty men of Charleston’s free people of color, most of whom would have been affiliated with the St. Philip’s Episcopal Church. Most of these men were of the artisan community or business entrepreneurs. Some of their original goals were assisting widows and orphans of members, providing burial plots, and other various services. At one point in the early nineteenth century they established a school for free people of color. This school was established by Thomas Bonneau in 1807 in Richard Holloway’s yard, for the children of the society’s members. They also supported and educated a young orphan who later became a bishop in the AME Church.

The Society used their treasury as a sort of revolving fund to provide capital for enterprising members who wanted to get involved in real estate or make investments in other endeavors. At one point the Brown Fellowship Society gained a large amount of real estate from the College of Charleston starting in 1794 and on up until 1820. The society then converted the real estate to bank stocks because they determined that they would receive a greater return. By 1856, the society’s original investment was worth $6,000, which was then shared by the members. As a part of this financial support, the society also functioned as a sort of credit union, allowing its members to borrow from its treasury.

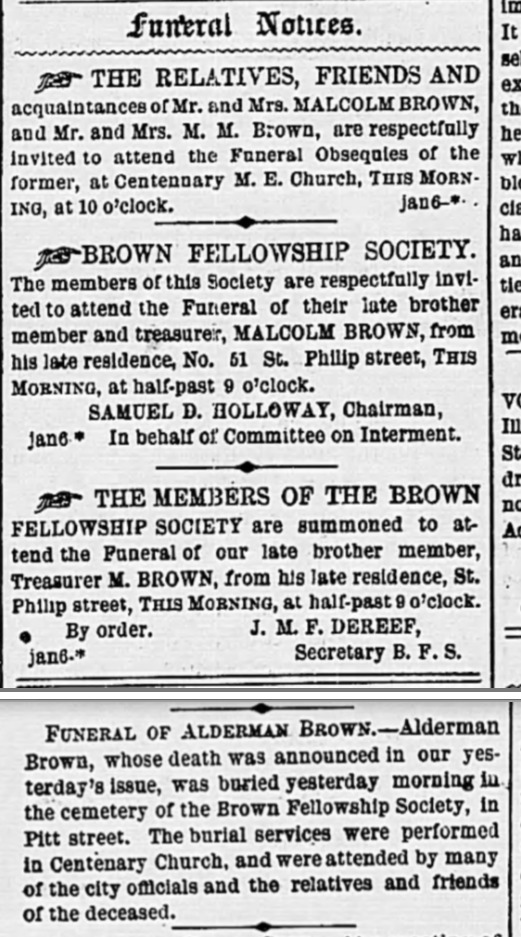

One of the main benefits of the society was the use of its cemetery. Because these free people of color were not allowed to be buried in St. Philip’s Episcopal Churchyard Cemetery, they founded their own. Both members and their families could be buried in the Society’s cemetery upon their death. If for any reason a member who died did not leave behind enough money to provide for burial cost and to support their children, the society would assume their burden. The society would financially support and educate their children until they reached the age of fourteen, at which time they would be apprenticed out to craftsmen until they became an adult. The people buried in that cemetery include some of the most affluent members of Charleston’s free Black community.

At least three more African American cemeteries opened here: The Machpelah Society, taking its name from the Tomb of the Patriarchs (Machpelah) in the Old Testament; Plymouth Church, a nearby African American Congregational Church; and the Free Dark Men Society, another antebellum organization of free people of color.

Burials in the cemetery continued well into the 1900s, until the property was purchased by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston so that a parking lot could be paved for Bishop England High School. Despite promising to relocate the headstones, monuments, and remains to the new graveyard located off of Cunnington Avenue, there is no evidence that this occurred. Most of the remains were never removed, and very few of the gravestones were relocated. Bishop England paved over the history of Charleston’s Black community as if it did not exist.

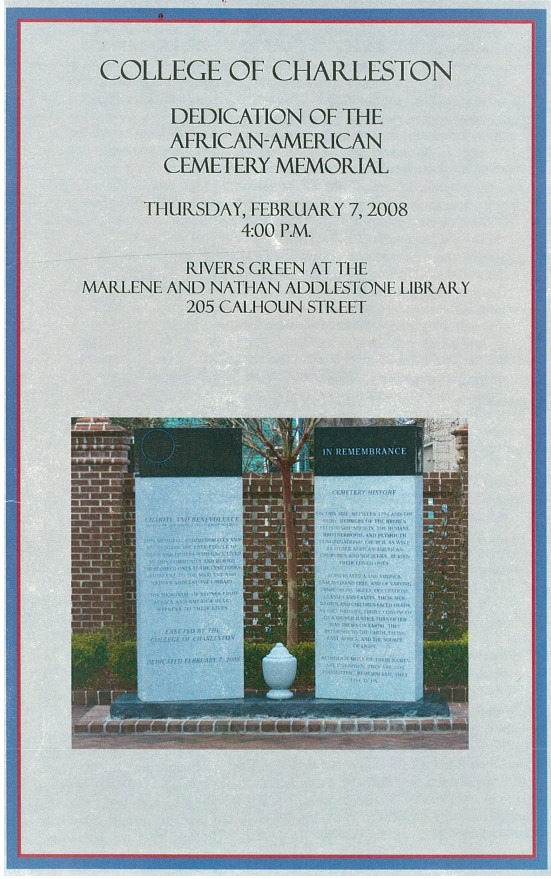

Recognition finally came after the construction of Addlestone Library, when the College of Charleston erected a monument in honor of those who were buried on the property. The College of Charleston held a dedication ceremony for the African-American Cemetery Memorial on February 7th, 2008 at Rivers Green of the Marlene and Nathan Addlestone Library. Some of those in attendance included the Dean of Libraries at the College of Charleston, the President of the College of Charleston, College of Charleston History Professor Dr. Bernard Powers Jr., and Mr. Anthony B. O’Neill, President of the Brown Fellowship Society. In the Program for the Dedication Dr. Powers writes, “By recognizing the African-American cemeteries as an important site of memory, a significant chapter is being written in Charleston’s modern history. Simultaneously, homage is being paid to its past.” To Dr. Powers, “This location adjacent to the Addlestone Library at the College of Charleston is especially compelling because the men in these organizations were interested in promoting education.”

Elsewhere on Rivers Green, tucked in a small garden at the southeast corner of the building, between the terrace and a fence along Coming Street, a memorial to a more recent community member and educator can be found. The memorial pays tribute to librarian Cynthia Graham Hurd, who was one of the victims of the tragic Mother Emanuel shooting on June 17, 2015. Graham was a beloved librarian at Addlestone and at the Charleston County Library.

Images