14 Green Way

Built for an African American during Reconstruction, later served as a women’s residence hall

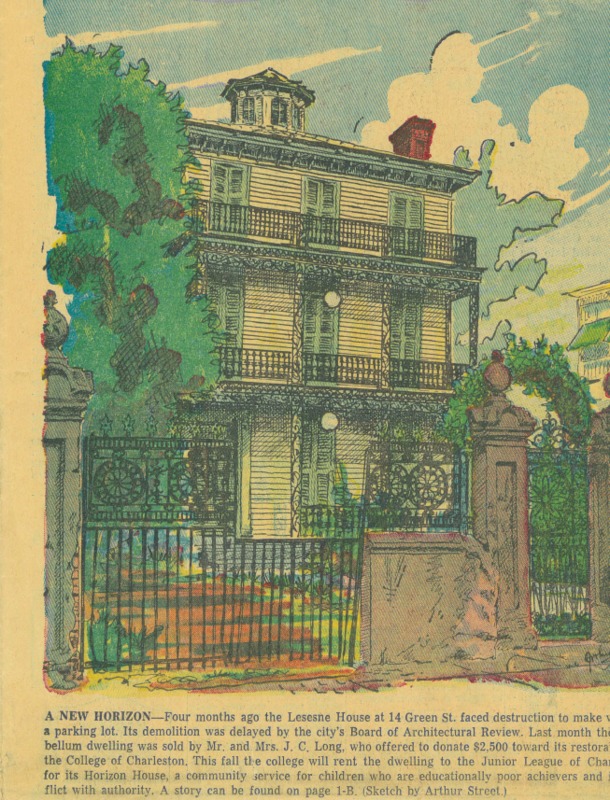

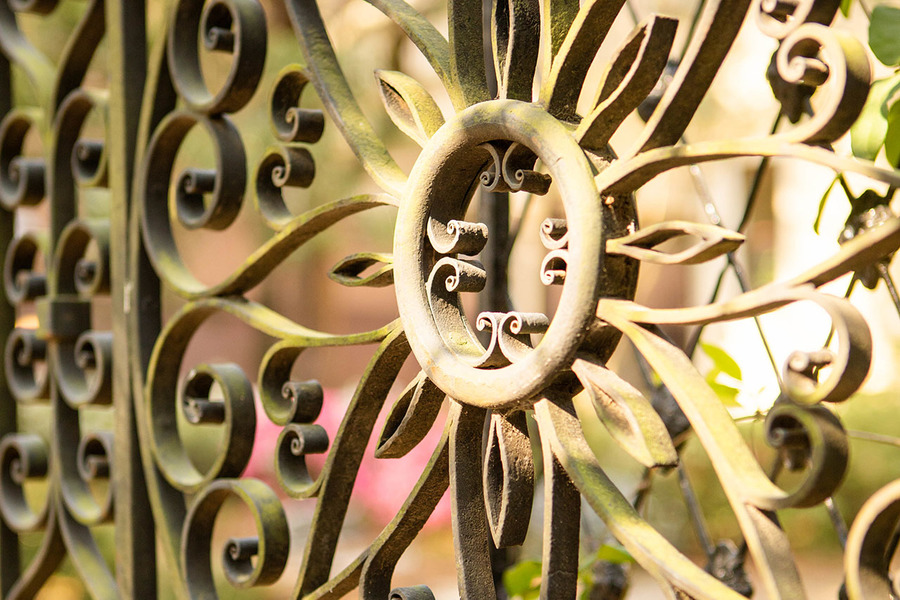

Decorated with elaborate ironwork and a distinctive cupola, this house was built in 1872 for A.O. Jones, African American and clerk of the South Carolina House of Representatives during Reconstruction.

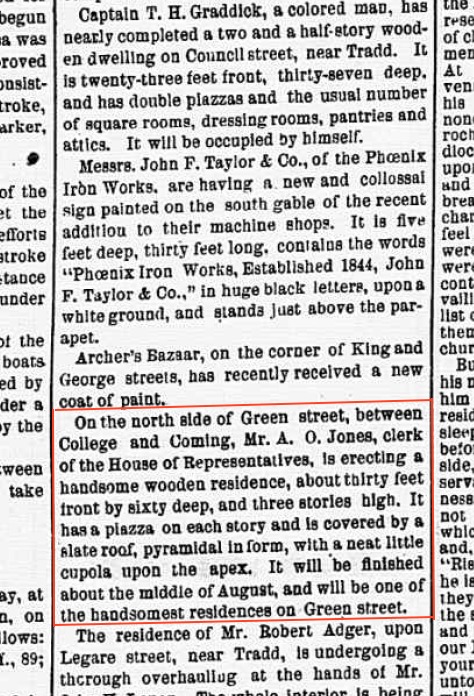

The College first owned this property from 1770 until 1817, when it sold some of its land to satisfy debts. Carpenter Walter Knox purchased this lot and probably built the two-story house that stood on it for decades. In 1870 his widow, Catherine Knox, sold the property to Albert Osceola Jones. An 1872 newspaper article reports, “Mr. A. O. Jones. . . is erecting a handsome wooden edifice . . . three stories high. It has a piazza on each story. . . with a neat little cupola on the apex.”

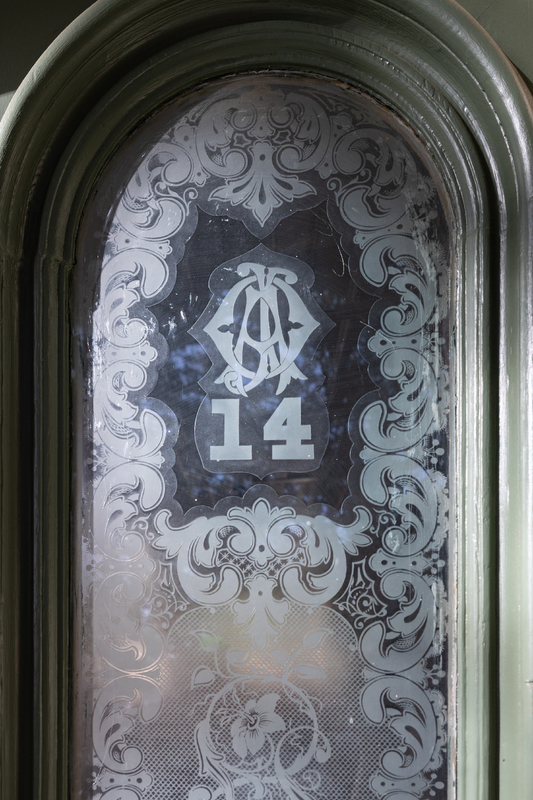

Most published accounts of this house’s history do not record A.O. Jones as the person for whom the structure was built. A free person of color listed as “mulatto” in the 1860 census, Jones grew up in Washington, D.C., where his father was a successful feed and livestock merchant. After the Civil War, when in his 20s, Jones moved to South Carolina and served as clerk of the South Carolina House of Representatives from 1868-1876. Intelligent and ambitious, Jones moved in 1872 into 14 Green St., a house large enough for his growing family, with elaborate ironwork decorating each piazza and Jones’s initials etched into the glass of the front door along with the number 14.

Available records have not disclosed all there is to know about Jones. Although he owned additional properties in Charleston and elsewhere in South Carolina, he lost the Green Street house to foreclosure in 1881. After Reconstruction, his job as clerk of the Republican-controlled House had ended when the Democrats regained power in 1876, following elections in which there was widespread evidence of fraud. A few months later, several Republicans including Jones were arrested and accused of misappropriating state funds, and although never convicted, Jones was among those vilified as corrupt and unfit by Democratic politicians and white-owned newspapers.

In 1879 the city directory, prepared under a post-Reconstruction administration, identified Jones as “laborer,” but a loan document shows that this same year Jones owned two typewriters – state-of-the-art technology – in addition to other furnishings valuable enough to secure a second mortgage. In 1880, he successfully farmed over 200 acres he owned in Beaufort, South Carolina, where he lived with his wife Estelle, four children and a German nanny.

These details, together with the incompleteness of published accounts of the house’s history, reflect the post-Civil War experiences and near-invisibility of many other African Americans in a majority-black state, whose 1868 constitution had given the franchise to men of all races. Deliberately forgotten by some, these individuals nevertheless worked to improve their lives in a new landscape where slavery had been abolished.

After Jones lost his house to foreclosure, 14 Green St., was owned by a series of middle-class Charlestonians, including a grocer and a King Street shoe store manager. In 1899, the College rented this house for use as a dormitory. Edward T. H. Shaffer, class of 1902 and author of Carolina Gardens (1937), lived here while a student at the College, which he described as “a kindergarten of Charleston’s lingering 18th century caste system.” Of the house, he wrote, “There was a relic of past grandeur in the front yard, a fountain where a mottled cherub patiently held aloft an iron umbrella regardless of the fact that no water ever flowed from it. Some wag on the faculty dubbed the establishment ‘The Sign of the Baby,’ and the name stuck until the dormitory was moved to other quarters.” The College relocated its dormitory to 4 Green St. when that property came up for sale in 1901.

Architectural historians named the house for the Knox family, who owned the lot for 53 years, and for the Lesesne family, who owned and occupied it from 1918 to 1961. Charles and Frieda Tice bought it in 1961, but were unable to complete restorations. A 1964 Preservation Society newlsetter (which notes, “during Reconstruction, the house was occupied by Negroes”) reports that when Tice offered the house for sale, he was contacted by a New Jersey resident who said he was A.O. Jones’s descendant. The house was sold to the family of developer J.C. Long, who unsuccessfully sought a permit to raze it before selling it and the adjacent Sottile House to the College in May 1964.

By the early 1960s, the College was buying all the nearby properties it could purchase, sometimes using endowment funds at the expense of scholarships or operating budgets. The College needed more space to expand, but many trustees and President George Grice were also seeking to remove low-income renters and African Americans from the neighborhood. Minutes from a 1962 Board meeting state that “parcels of property now on the market are paralleled by an increase of Negro tenants and owners occupying houses and apartments in the area of Coming Street south of Calhoun.” The College, which had long been a city college, had gone private in 1949 under President Grice in order to avoid integration. Segregationist efforts ultimately failed; the College began admitting black students in 1967 and became a state institution in 1970.

The Preservation Society gave the College a Carolopolis Award for saving 14 Green St. from demolition in 1964. For a few years in the 1960s, the College rented it to the Junior League of Charleston, a women’s volunteer service organization, which operated Horizon House, a residence for troubled children. The College renovated the house in 1972-73, after Green Street had become the pedestrian-only Green Way. It was used as a women’s dormitory until 2013. Currently 14 Green Way is home to the College's Office of Multicultural Student Programs and Services. Renovated in 2018, the house now has solar panels that generate about 25 percent of its energy.

Audio

Images