Fort Johnson Monument

One of many monuments glorifying the Confederacy

The Charleston Confederate War Centennial Commission, chaired by Mrs. J. C. Long, gave this monument to the College of Charleston in 1961, one hundred years after the Civil War began. In Charleston, the centennial celebrated the Confederacy and promoted the racial caste system known as Jim Crow.

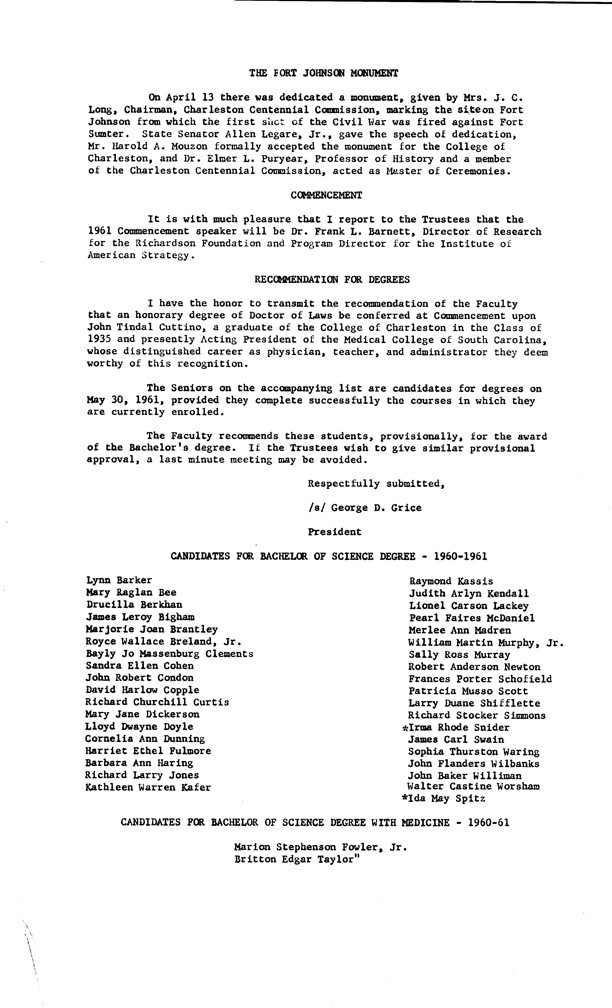

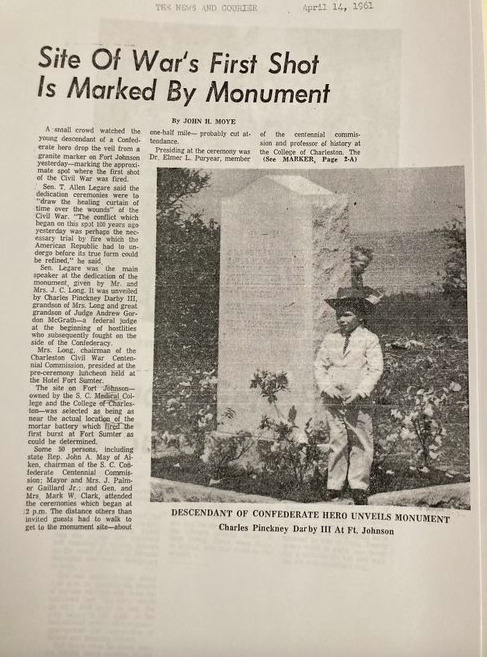

The Charleston Confederate War Centennial Commission, chaired by Mrs. J. C. Long, gave this monument to the College of Charleston on the hundredth anniversary of the start of the Civil War. College of Charleston History Professor Elmer L. Puryear, also a member of the Commission, presided over the dedication ceremony on April 13, 1961. The monument, the ceremony, and the Confederate War Centennial Commission itself were all part of a larger cultural campaign to perpetuate the racial caste system known as Jim Crow.

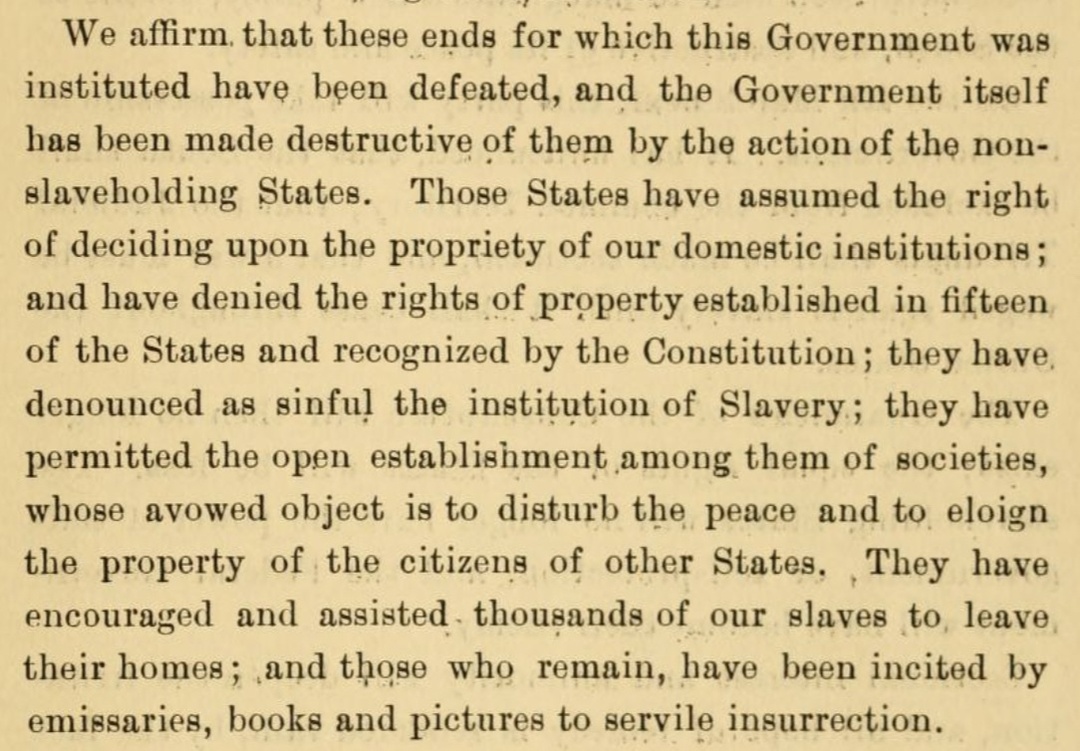

The monument commemorates the Confederates' firing on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1961 (see image 1). The bare facts stated on the monument are accurate, but they deliberately obscure the fact that Southern states seceded and started the war in order to establish a new nation based not on the truth that all men are created equal, but on slavery and racial inequality. (See Image 2.)

At first, the war seemed to give the United States its “new birth of freedom,” as Abraham Lincoln called it in his Gettysburg Address. Union troops—many of them Black soldiers—liberated Charleston on February 18, 1865. The entire insurrection collapsed a few months later. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution abolished slavery; granted full citizenship to everyone born in the U. S., regardless of race; and assured all citizens of the “equal protection of the laws.” During Reconstruction, more than 80,000 Black South Carolinians registered to vote, ratified a new state constitution, and exercised their inalienable right to self-government for the first time. They elected many Black legislators to both houses of the General Assembly.

But the proponents of inequality were resilient.

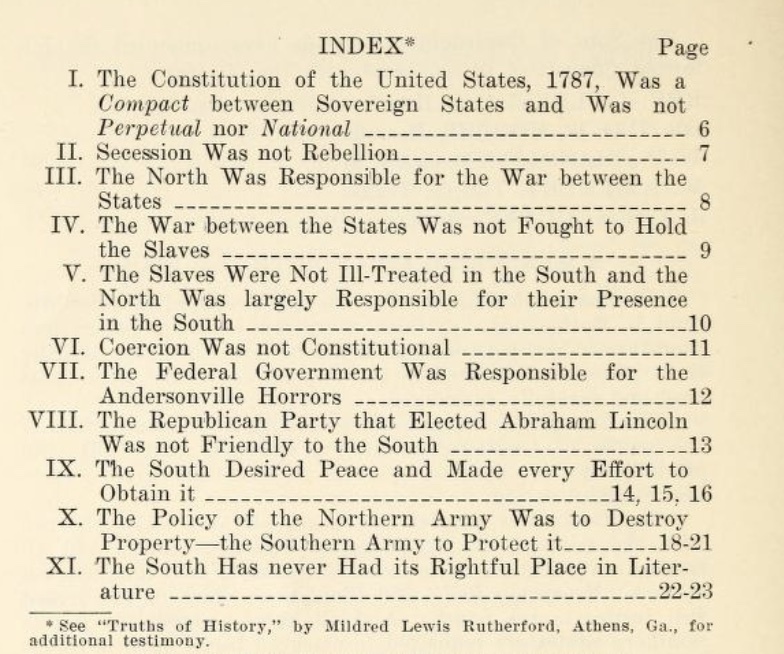

Almost the moment the Confederacy collapsed, certain white southerners began re-interpreting the Confederacy not as a mission to preserve and spread slavery, but as a noble cause of self-defense. Known today as the “Lost Cause” interpretation of history, this view holds that in 1861 northern aggressors disrupted a just society in which relations between Blacks and whites were cordial, stable, and in accord with nature. Nature itself made the races of humanity unequal. White people were manifestly superior in intellect and moral capacity, while Black people, suited to brute manual labor, were not fit and could not be made fit to exercise self-government. Democracy, they believed, was doomed by human nature.

While most white Southerners conceded that slavery was not coming back, many continued to insist that white supremacy was the proper basis of government. White supremacists intimidated and murdered Black and Republican voters. At first, the federal government intervened, using the Army to maintain civil rights in the South. But eventually, the white proponents of equality suffered what historians call “moral fatigue” and lost the will to protect civil rights. Between 1876 and 1896, a series of court cases, culminating in the notorious Plessy v Ferguson, allowed the states of the old Confederacy to re-establish inequality. South Carolina became a fake democracy in which a privileged minority imposed a segregated caste system, which came to be called “Jim Crow,” on the majority of its citizens.

The triumph of Jim Crow was reflected in mainstream culture. Monuments glorifying the Confederacy went up all over the South. The Calhoun Monument in Marion Square, erected in 1896, and the Monument to the Confederate Defenders of Fort Sumter at White Point Gardens, dedicated in 1932, are good examples of how public memory explicitly promoted the “Lost Cause” interpretation of the Civil War and implicitly reinforced the ideology of Jim Crow.

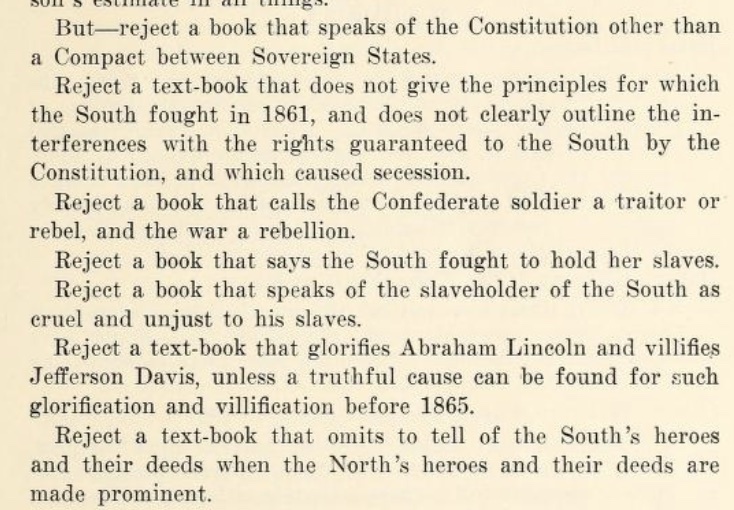

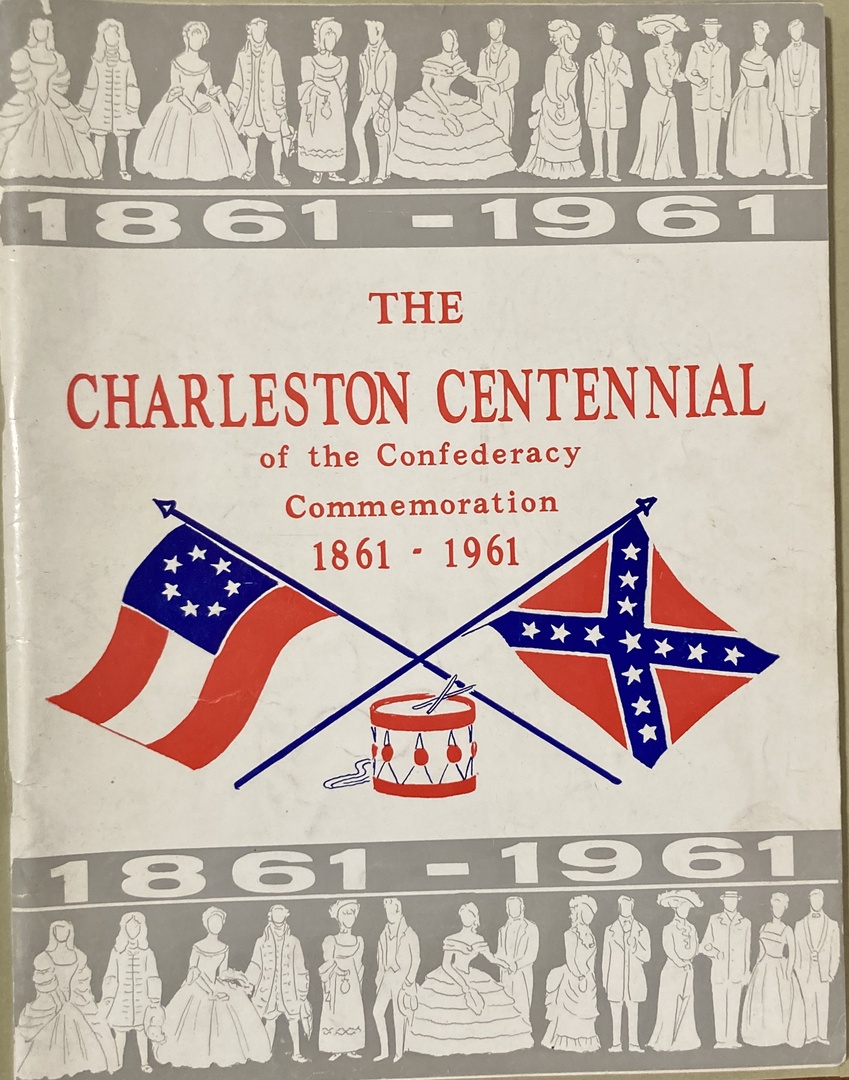

The centennial of the Civil War became a referendum on civil rights. E. Milroy Burton, the director of the Charleston Museum, insisted that Charleston must get its act together or the “Northern point of view”—that the Civil War was about racial equality—would prevail. An all-white commission was organized to protect the “Lost Cause” version of history.

The commission’s work began with its name. The national organization was the “Civil War Centennial Commission,” but the local branch named itself the “South Carolina Confederate War Centennial.” In 1961, calling the Civil War the “Confederate War,” the “War of Secession,” the “War Between the States,” or the “War of Northern Aggression” communicated one’s allegiance to Jim Crow.

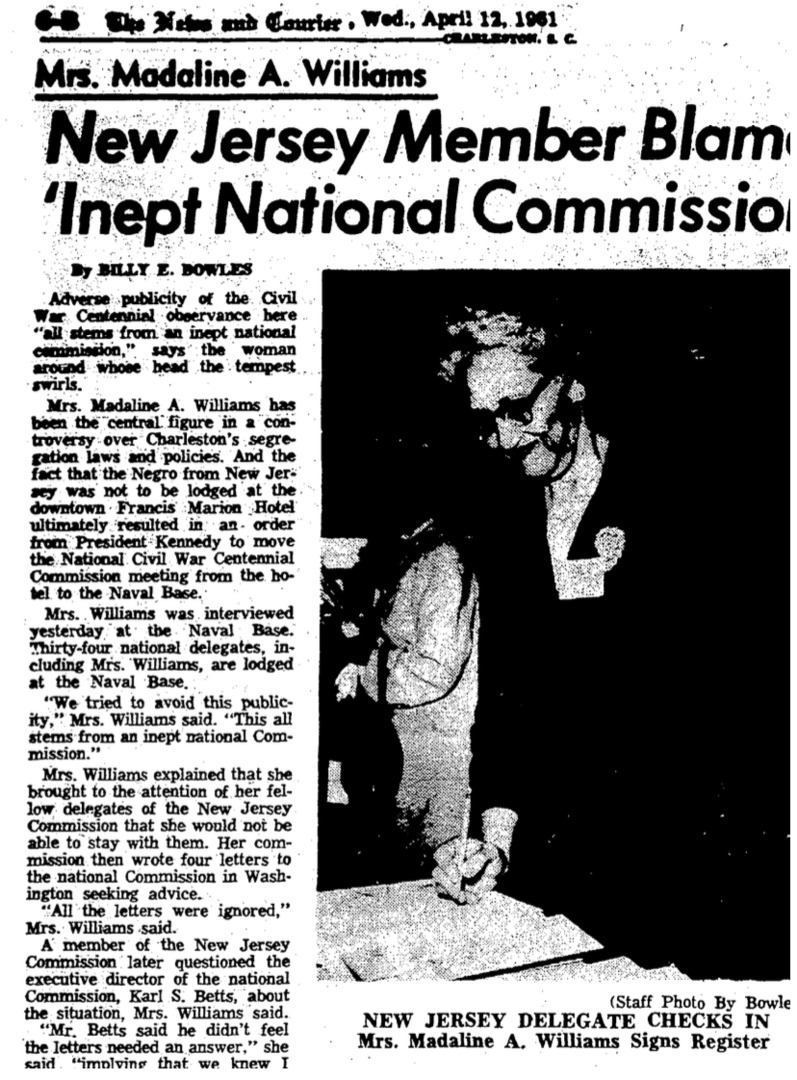

The national Centennial Commission had planned to convene in the Francis Marion Hotel, but that hotel was segregated, and Madaline Williams, a commission delegate from New Jersey, would not be able to stay there. Controversy ensued, and President Kennedy ultimately moved the Commission to the Naval Base in North Charleston, while the "Confederate War Centennial" continued to uphold its values.

On the eve of the centennial, South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond gave the keynote address to at the Confederate War Commission’s banquet. Equality, he explained, was never a principle of American political philosophy. It was a “Marxist idea,” and he called on “overzealous radicals” to give up their “integrationist idealism” so that America’s caste system might “triumph over the forces of communism."

“There was no bigger day for white Charleston” than the centennial, the journalist, Steve Bailey regretfully remembers. The ten-year old boy saw Alhambra Hall in Mt. Pleasant “decorated and awash in people who had come to watch the reenactment of the bombardment of the Union forces.” Everyone “cheered wildly” when the Confederates won. “There was never a question that day about whose side we were on.”

There is no doubt that in 1961, the College of Charleston was on the side of Jim Crow. The ceremony dedicating this monument was a relatively small part of the centennial events, just one in thousands of cultural artifacts perpetuating a racial caste society. Though petitioned by College of Charleston alumni and students to integrate the campus, President George Grice steadfastly defended white supremacist policies throughout his presidency. Threatened by financial ruin, the College finally began admitting Black students in 1967.

Images