As the 14th president (1945-65) of the College of Charleston (CofC), George D. Grice left a complicated legacy.

As the 14th president (1945-65) of the College of Charleston (CofC), George D. Grice left a complicated legacy. On the one hand, he created several enduring opportunities for faculty and students. For instance, in 1955 Grice founded the College’s Fort Johnson Marine Biological Laboratory, seeing potential in the Fort Johnson site that ran counter to advice of a scientific panel formed to gauge its suitability. He was encouraged in this effort by his son, George D. Grice, Jr., then a doctoral student who would become a prominent marine scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. The CofC marine laboratory has since served as a base of marine research and education for generations of faculty and students, involving the oldest marine biology undergraduate major on the east coast and a top-10 marine biology graduate program, soon to celebrate its 50th anniversary. He also implemented benefits for faculty across the school, notably by initiating participation in the South Carolina retirement plan, beginning a tenure system, instituting a sabbatical program, and raising faculty salaries to a competitive level.

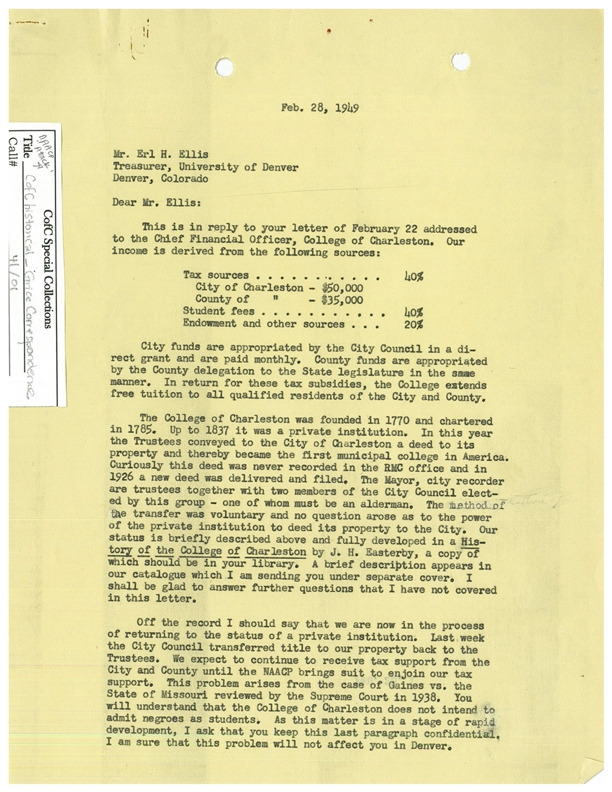

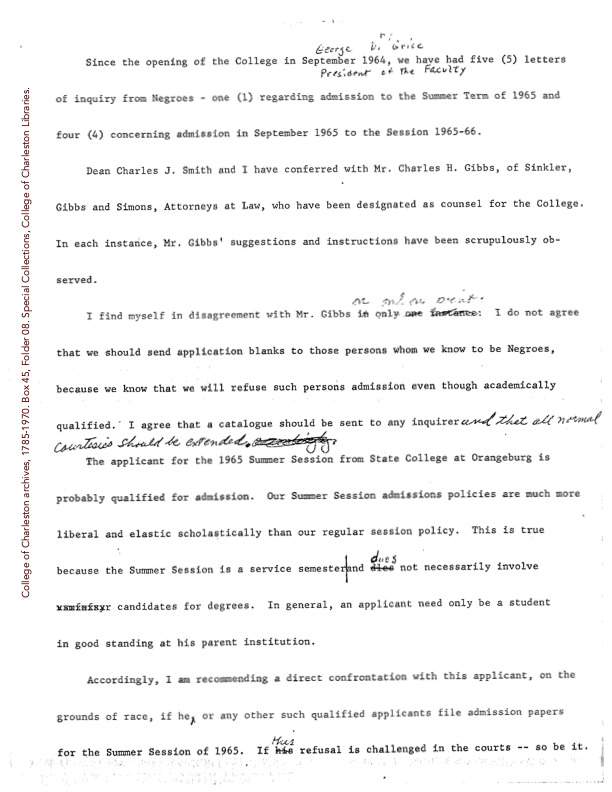

On the other hand, Grice’s policies and actions as CofC President—and later as a state senator—deliberately excluded minorities and women from opportunities in education and employment. During his tenure, applications to CofC from dozens of Black students received a form dismissal--“the policy of the College will not permit accepting an application from you”--and Grice encouraged direct legal confrontation with applicants who challenged this policy. As a member of Charleston’s White Citizens Council—an upper-class version of the Ku Klux Klan formed by white southerners to fight racial integration—he vowed “the relentless pursuit of the NAACP in the press and in the courts” (as quoted by White), and he helped to found the “Committee of 52,” a white resistance group that lobbied the state legislature to preserve segregation in education. To that end, in 1949 he oversaw the privatizing sale of the College for $1 from the city of Charleston to the Board of Trustees, distancing the College from government oversight. Similarly, Grice took steps toward limiting or phasing out female enrollment, which had begun under his predecessor, and vehemently opposed hiring female faculty “over my dead body” (as quoted by Morrison).

The historical record shows that Grice held to these policies even as alumni, faculty, students, local officials, and leaders of other state institutions disavowed them. In 1963, while Clemson University and University of South Carolina (USC) had begun to integrate peacefully, Grice accelerated divestment from federal funds to avoid forced integration, including a costly premature payment for Ft. Johnson, which would have eventually become CofC property without cost to the College. His real estate ambitions also involved an obsessive practice of buying up properties surrounding the downtown campus. While these purchases ultimately allowed for the growth of the campus and student body, they also drained the endowment and brought the College close to financial ruin. Moreover, Grice’s statements provide evidence that part of his motivation was to clear nearby neighborhoods of Black residents (as concluded by Morrison).

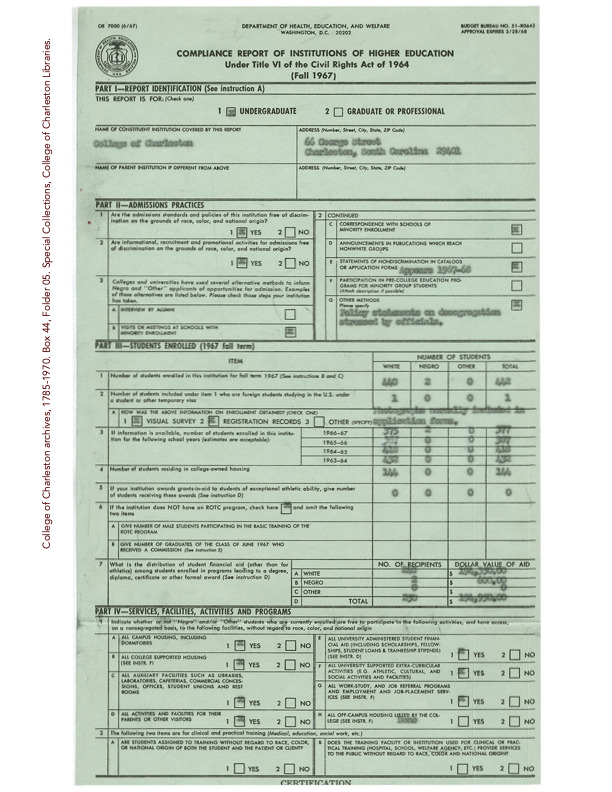

In 1965, in a final effort to shield the College from federal enforcement of school integration, Grice refused to sign the Compliance Clause required under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which mandated equal access to any program receiving federal assistance. This stance led to financial hardship for many students as they lost access to federal loans, and it excluded CofC faculty from applying for federal grants. He defiantly told some faculty near the end of his tenure that he was prepared for CofC to be the last segregated school in America.

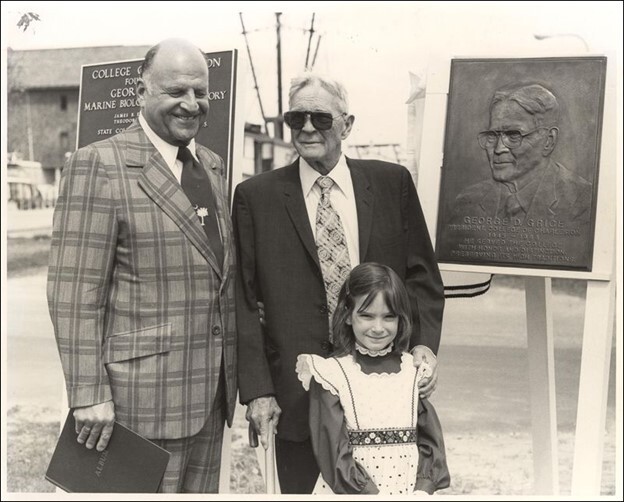

Although Grice served longer than any CofC President since his tenure, his legacy is entirely omitted from the College’s “History and Traditions” web pages. Fortunately, that legacy was researched and reported in Nan Morrison’s (2011) book, which was a main source of information for this essay. Ten years after his presidency, the marine laboratory Grice founded was renamed in his honor and a plaque was mounted at its entrance, lauding him for preserving the College’s “high traditions”—perhaps a reaction to more progressive changes by Presidents Coppedge and Stern that began to reverse the College’s exclusionary practices. Discovering the College’s past under Grice reveals that preserving such traditions included his steadfast implementation of racist and sexist policies. Ironically, the seal of the institution Grice served—which depicts a diploma-bearing CofC graduate framed by the phrase Sapientia Ipsa Libertas, “Wisdom itself is liberty”—speaks to the injustices he perpetuated by denying equal access to education as a means to social and economic liberation.

Images